PROVINCETOWN — As recently as 10 years ago, there was only one oyster farmer in Provincetown, and his efforts were small scale and experimental.

Nine farmers now land Provincetown oysters at MacMillan Pier and aquaculture operations are approved on 25 acres of deep water in the East End and 38 acres of tidal flats in the West End.

Total output is still small compared to more famous oyster-producing towns. While Provincetown lands about 250,000 oysters a year, Wellfleet brings in 9 to 10 million.

But there is more acreage available for grants and no waiting list in Provincetown for them, and the town sees aquaculture as a promising arena for economic development, with plans to get another 100 acres of tidal flats approved.

Provincetown’s homegrown oysters currently supply only about 10 percent of the town’s oyster consumption, according to distributor Chris King of Cape Tip Seafood. But in just four years, oyster production has grown tenfold due to the efforts of many people and lots of trial and error, according to Provincetown Shellfish Constable Steve Wisbauer.

“Thirty years ago, the tidal flats near the Long Point breakwater were farmed for quahogs,” said Wisbauer, “but a mysterious parasite wiped them out in the early 1990s. Only Alex Brown continued farming in the flats after that disaster. He switched to oysters, and kept working his grant out there at a relatively smaller scale ever since.”

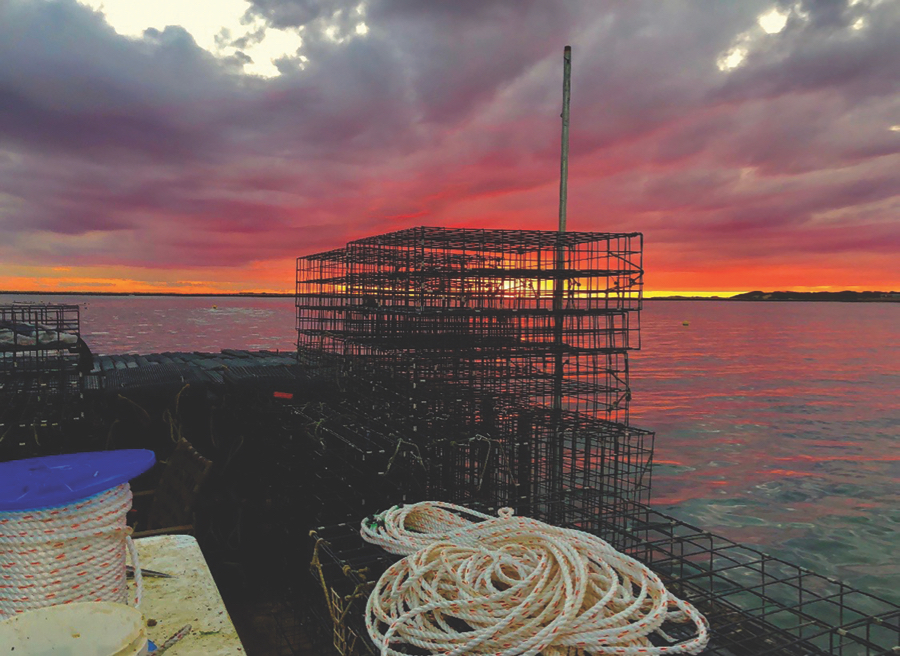

A deepwater farming site was established in 2013 in the waters off Beach Point, straddling the Provincetown-Truro town line, following extensive negotiations with the state Div. of Marine Fisheries and other agencies. Those efforts were led by Tony Jackett, who served as shellfish constable for both Provincetown and Truro for 18 years, and currently serves as shellfish constable and harbormaster in Truro. The deepwater farming site consists of 50 acres, half on each side of the town line, in which growers use floating oyster cages that never touch the floor of the harbor.

Several of the first oyster farmers in that aquaculture development area, or ADA, still have active grants there, including Lory and John Santos of Provincetown and Dana Pazolt of Truro. Some growers have their oysters spend their entire two-to-three-year life cycle in cages floating in deep water, while several of the growers began to explore moving the oysters to tidal flats after six months of growth. The tidal flats near the Long Point breakwater are an easier place to work, said oyster farmer Ted Cormay.

“The thing about deep water is, you have to do everything leaning over the edge of your boat,” Cormay said. “I have a 17-foot Boston whaler. It’s plenty stable, but it’s still an awkward position from which to lift and bend and haul gear. In the tidal flats, at low tide you have your two feet on the ground. Even as the tide starts to come in, until it’s up to your waist, you can lift and turn and just move more effectively out there.”

Most of the Provincetown growers who harvested mature oysters in 2019 have grants in both deep water and tidal flats.

“We’ve all experimented with different places to raise the seed,” continued Cormay. “You order oysters from the nursery as tiny animals. The two-millimeter animals look like a shoebox full of quinoa — or you can order them as large as three-quarter inches, which are more likely to survive, but of course they cost more. The tiny seed, the two- or six-millimeter ones, are really vulnerable. You can’t start them out on the flats or they’ll be eaten alive by the green crabs and Asian crabs that are everywhere out there.

“Steve [Wisbauer] had a few different places for us to try,” Cormay added. “There was a water circulating apparatus on the dinghy dock for a while, and we had the seed in cages out there. We had them at Bennett Pier — it’s a small pier next to the courtesy float between MacMillan Pier and the P’town Marina. And we had them out in the deep-water grants as well. Right now I start my oysters out in the deep-water grant in June or July and leave them there until early November. Then I move them to the tidal flats for the rest of their lives. They’re big enough to survive out there by November — their shells are hard enough to protect them — and it’s an easier place to do all the rest of the work.”

Oysters require a lot of work throughout their life cycle, principally because they grow at dramatically different rates, and they have to be sorted, like size with like, so they can be put in bags with the best possible water circulation. Also, the bags and cages are constantly being fouled by seaweed and muck, which impedes water circulation and deprives the oysters of nutrition, which slows growth. So the principal physical work involves cleaning the cages and bags with a saltwater power-washer, and then opening the bags, sorting the animals, and putting them back in bags.

“Say you’ve got 60 cages, each with six bags in it,” said Provincetown oysterman Alfred Famiglietti. “So, 360 bags. And they’re each going to be opened and sorted maybe twice a year, and each bag has to be power-washed about once a month. And you can only work for four hours at low tide, and sometimes low tide is at 6 a.m. and 6 p.m. And then say you lose three days to wind and storm, like we just did. There’s a lot of work that has to be done, physical work, and it winds up happening at the strangest times of day.”

“It’s about 40 hours a week between May and November,” said Cormay, “with really not much to do in the winter. Except you don’t get paid for the first three years, and you have to put a fair amount of cash into it for equipment. It’s a younger person’s work, physically speaking, but a lot of younger people don’t have the luxury of putting in three years and not knowing what the return will be. On the other hand, you’re out on the water. It’s a nice place to have an office. And if you do make it to a good harvest, then, yeah, the numbers can work out.”

Reviving a Historic Shellfishing Area

Getting the historic quahog grant area in the tidal flats revived and re-permitted for oyster farming was fiendishly complex, Wisbauer said.

“Put down your pen — you won’t be able to keep up,” Wisbauer told a reporter, listing about nine agencies or applications that were involved in getting a 38.7-acre area near the breakwater approved for aquaculture grants.

Wisbauer is now working to expand that approved area by as much as 100 acres (none of which are within the existing recreational shellfish zones). But that will first require a two-year study of the roseate and common terns that are seasonally present in the tidal flats.

“It’s a process to get this area designated, and it’s also a process to figure out the most efficient way to use an acre,” Wisbauer said. “It’s not just about raw acreage. Changing your farming techniques can dramatically change your results. But putting these pieces together is something the town is really committed to seeing through.

“Provincetown has had a change of mind and direction about what is going to power the economy, and this industry is proof,” he added. “Condo conversions were the economic engine of Provincetown for 20 years. It paid the contractors. It increased the value of real estate. That is mostly played out now. It’s all been converted, and now every committee in town is talking about the same problem: we have 3,000 people and no year-round jobs and nowhere to live. This is part of addressing that. It’s in the harbor plan; it’s in the economic development action plan; the select board supports it. The ‘blue economy,’ farming the ocean — it’s the future.

“What we are doing here, it’s still pretty small,” Wisbauer concluded. “But there’s a community behind it. We’re probably the only town in Massachusetts that has no waitlist for a grant, where you can walk in and people will help you through the permitting process and help you get started. The town owns the flats, and there’s grants available. Not a lot of towns can say that.”