Zeinab Shahidi Marnani, a visual arts fellow at Provincetown’s Fine Arts Work Center, spends a lot of time in relative isolation. “Seven months is a long time,” she says. She’s been thinking about distance — especially the experience of distancing oneself from what is known.

One of her artworks is painted directly onto the floor and wall of her studio in the shape of a piece of paper folded in half. Shahidi calls it an experiment. “When you have a long period of time,” she says, “you can open projects that were always ideas.”

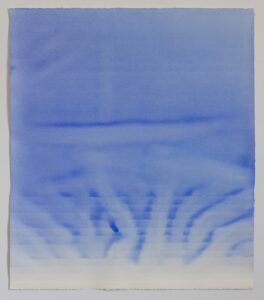

In this painting, dark swooping marks stand out against the white background, looking like the bottoms of billowing clouds, or the silhouettes of seabirds, or the outlines of gentle waves. Straight, tapering lines appear among them: those are the letter “alef,” Shahidi explains: the first letter in the Farsi alphabet.

The swooping shape is called “madd”: a symbol that, when placed over “alef,” elongates the vowel sound. On its own, “madd” translates to “high tide.”

But the point isn’t translation, says Shahidi — it isn’t even to recognize that the mark is part of a language. “I didn’t want to write a poem in Farsi for you,” she says, “and you couldn’t read it.” She just likes the shape, especially arranged in a pattern to represent water.

The dark marks are made with a liquid material between acrylic and ink, says Shahidi, that her friend Dani Levine, also a FAWC fellow, made for her. “The color is so nice,” she says. “It has a little bit of blue and a little bit of sparkle inside.”

Shahidi took classes in typography and calligraphy in Iran. There, she says, she’d never make a painting out of the separate pieces of Farsi letters. “Now that I’m here,” she says, “speaking this other language, I’m looking from the outside onto my own.” At a distance, broken down and isolated, language becomes landscape.

Shahidi was born in 1983 in Isfahan, a city in central Iran. She says she doesn’t remember a time when she wasn’t making art. “I always knew that it was a thing to be an artist,” she says. “All those things that kids do but maybe don’t take seriously — for some reason I took them seriously. Even playing with play dough.”

Before Shahidi could read or write, she told stories with colored pencils and watercolor. She made storyboards full of people interacting, enacting the drama of the everyday.

Her parents weren’t artists by profession. But her father made paintings and photographs and as a child had built a projector to play movies at home, and her mother designed and made all of her children’s clothes. Shahidi has kept those clothes — she sometimes thinks of exhibiting them. It was her parents who inspired her to pursue art, she says. “I remember my mom calling me a painter since I was little,” she says. Shahidi studied visual communications at the University of Tehran, and in 2009, she enrolled at Yale University to study sculpture. Now she lives in Tehran and New York City.

She went through a stage when she made videos. For one documentary project, she filmed artists talking about their art. In a different video project, she says, “I made people tell a story.”

Then Shahidi made collages out of her videos: characters and scenes overlapped, sewn together “as if the whole film compressed into one single frame,” she says.

There was another period when she became interested in light and vision. “I made a few camera obscuras,” she says. As a FAWC fellow last year, she cut holes in shoeboxes and invited the viewer to peer inside at a white paper circle. One’s vision warped, and the circle dissevered; the viewers’ eyes conjured new images.

The work in Shahidi’s Provincetown studio reflects her current interest in the “still frame” — things that “stand outside of time.”

On the wall are three pieces of paper folded in half so that their lower halves jut out from the wall; their upper halves are secured by push-pins. “It’s part of my own process to question everything,” says Shahidi. “Even the medium itself.” She asked herself, “Why are paintings always flat?”

The folded pieces of paper are painted with ink. One resembles the sun setting over the ocean, sinking, half-hidden, into the crease, and the water, drawn in small black marks on the horizontal part of the paper, bouncing gently in the open air. One shows a door, shut; the lower half of the paper is blank.

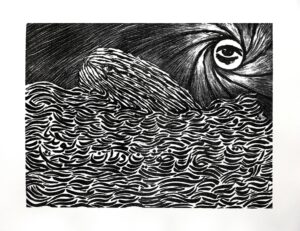

She’s been working on a drawing in ink made by tracing the edge of a piece of cardboard, the lines intersecting and interacting like a two-dimensional hall of mirrors. The lines are the shape that you see when you look at your own nose: the curve down to a small point, the top of the round cheek visible underneath.

“When you close one eye, you see it clearly,” says Shahidi, closing one of her eyes and crossing the other to demonstrate. “When both eyes are open, it’s a bit more difficult to focus on what you have.” It can be done by crossing your eyes and looking inward, but the image is unclear.

Darker, bolder shapes emerge from the thin lines. Those are Shahidi’s hairs, she says, drifting into her line of sight. At the beach, looking at the sea, she experiments with her vision. “I never noticed that my hairs are part of the image,” she says. The shapes are also Farsi letters: the letter “eyn,” a shape almost like a capital English “E” in cursive.

The result is a drawing that feels intensely personal: the artist’s view of her own nose and hair without a mirror, an impossible distance captured and flattened. A solid black half-circle near the middle of the drawing is the sun, says Shahidi. The viewer can almost feel the heat; the sensation of blinking away light coming from far away. The moment certainly seems to stand outside of time: no story here, just an instant of quiet solitude, drawn out.

Shahidi is interested in water, she says; not only drawing it but using it as a material. “Ink has a liquid quality that is so different from using a pen,” she says. “Everything is water around me now.”

On the other side of the small studio, several large sheets of paper lie on the floor. They resemble intricate topographic maps, drawn in pale gray. But Shahidi didn’t draw them. The marbling technique is a traditional one used in Japan, she says: she deposits a drop of ink and a drop of soapy water, then repeats hundreds of times until the landscapes create themselves and fill the page.

“We have the technique in Iran,” she says. It’s called abr-o-bâd: “The cloud and the wind,” she says it means.

Shahidi tries to visit the ocean every day to look at the water. “I miss it whenever I don’t go,” she says. She goes in the morning or whenever she needs a moment. “Before I start everything,” she says, “and whenever I’m frustrated.

“I can’t call it loving something,” says Shahidi about her interest in the sea. “I’ve never thought about it like that.” She considers a moment longer: “It probably is love.”