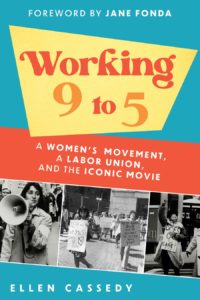

While the phrase “workin’ 9 to 5” immediately evokes the bouncy vocals of Dolly Parton, her song — and the movie it was written for — are indebted to a movement of women workers that shared that name. In her book Working 9 to 5, Ellen Cassedy, a summer resident of Truro, chronicles how that movement grew from a cadre of friends publishing and distributing a zine at Boston T stops to a nationwide organization to unionize office workers.

Founded in Boston in 1973, 9 to 5 brought together secretarial workers across all industries to fight for better wages and working conditions. Regardless of their qualifications, most of these women found themselves hired as “10 fingers” tasked with training the men who were promoted above them. Regularly asked to do their bosses’ personal chores on top of their normal workload, women ran the office while being treated as if they were little more than appendages of the telephone, typewriter, or copier. (Cassedy recalls an advertisement of the time that said, “This machine is just like your secretary: silent, efficient, and easily manipulable.”)

By digging through the organization’s papers in the Harvard archives, the labor archives at Wayne State University in Detroit, the Midwest Academy archives in Chicago, and her own letters, Cassedy assembled a compelling narrative of how she and the other “9 to 5ers” translated their passion for women’s rights into language their sister secretaries would accept.

“I kept hearing ‘I believe women should be treated equally on the job,’ ” Cassedy recalls. “But then I’d hear ‘But I am not a feminist or women’s libber.’ ” One of the book’s most fascinating themes is how the movement negotiated that distinction. For Cassedy and other organizers who had come of age in the antiwar movement, their personal values were often much more radical than those of the working women they hoped to recruit.

“We didn’t let our vocabulary stand in the way of bringing people into the group,” Cassedy says. Thanks to her activist training at the Midwest Academy, she learned how the organizer’s first task is to listen — and by eating thousands of lunches in company canteens (sometimes three a day) the 9 to 5ers tailored their recruitment pitches to the people they meant to serve.

Cassedy and her peers distributed questionnaires about women’s work experiences. They drafted a bill of rights with their ideas to improve office life. They met with attorneys who applied legal pressure to businesses engaged in discriminatory practices. And they began to stage events — like the “Petty Office Rewards” contest — presenting the worst offending bosses with trophies and invited local news stations to cover them. (The first winner was a boss who demanded his secretary stitch up a rip in his pants while he was wearing them.)

Cassedy’s book is peppered with such anecdotes and memories of how the movement used humor to unite its members. Their efforts shifted the climate in Boston and the nation at large: wages increased, women were protected from being fired for being pregnant, and women labor leaders emerged. As the movement expanded beyond Boston, the organization also worked to promote racially diverse leadership.

And then Hollywood came calling. One of Cassedy’s colleagues had known Jane Fonda in the antiwar movement, and inspired by the group’s work, Fonda came to interview its members about working conditions, gripes, and revenge fantasies. The 1980 movie 9 to 5 is full of scenes inspired by those stories. “The movie proved that women ran the office,” Cassedy says. “Through humor, the point was made.”

Cassedy says her experience isn’t meant as a prescription. “Today’s activists are going to figure it out for themselves, and that’s how it should be,” she says. Still, its lessons on how to build coalitions across political lines are especially compelling and pertinent.

At a recent reunion, Cassedy collected the advice that 9 to 5ers want to offer the next generation: “The fight is never over, because it’s always about power: who has it, who doesn’t, who needs it, and how they get it,” she says. “Never pass up an opportunity to organize.”