This article was updated on Nov. 8.

Two companies have won leases for four of the eight available wind energy areas that were selected by the Interior Dept.’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) in May.

This is the government’s sixth offshore wind lease sale and the first commercial sale for floating offshore wind on the U.S. Atlantic coast, according to BOEM’s announcement. The leased areas, the agency says, have the potential to power more than 2.3 million homes.

The lease sales, made on Oct. 29, do not authorize the construction or operation of wind energy facilities. Instead, they give the two companies the right to submit plans. They also lay out a number of requirements that will shape any proposals.

Two of the leases went to American-owned Invenergy NE Offshore Wind, LLC and two to Avangrid Renewables, LLC, a partial subsidiary of the Spanish energy giant Iberdrola. Each of the four lease areas was purchased for the minimum bid of $50 per acre, totaling $21,954,800 for just under 440,000 acres.

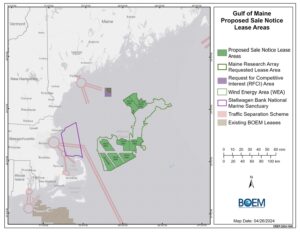

Three of the areas are closest to Massachusetts. The nearest to shore, which was leased to Invenergy, is 24.8 miles from the Outer Cape. The other two Massachusetts areas are each 40 miles from the Outer Cape and were leased to Avangrid. The fourth lease area is 53.2 miles from the coast of Maine.

Included in the nearly $22 million total is $2.7 million in “bidding credits” to go to fisheries compensation mitigation and another $2.7 million destined for workforce training and domestic supply chain development. The leases also stipulate that the companies must “make every reasonable effort” to enter into project labor agreements and develop communication plans with tribes, agencies, and the fishing industry.

According to a May 2024 report from NOAA Fisheries, fishing in the three Massachusetts areas that were sold resulted in total revenue of $3,523,000 in 2022. Provincetown was among the top five ports of landing for vessels operating in these four lease areas.

As for the four lease areas that did not receive any bids, BOEM’s auction schedule includes a second Gulf of Maine lease auction in 2028, but whether those four areas will be re-auctioned at that point will depend on analysis of the Oct. 29 sale, said BOEM public affairs specialist Victoria Peabody.

This auction is not the first to have lease areas receive no bids. When BOEM auctioned three lease areas in the Gulf of Mexico in August 2023, two of the leases received no bids, and the other was sold for approximately $54.64 per acre. BOEM also postponed the auction of wind energy areas off the coast of Oregon this September “due to insufficient bidder interest.”

Most other offshore wind lease areas have sold for far more than these Gulf of Maine leases did. Three lease areas south of Massachusetts sold for an average of $1,039 per acre in 2018 — over 20 times the value of the Gulf of Maine offshore wind energy areas. And the Biden administration’s first wind energy area auction off New York and New Jersey sold for an average of $8,951 per acre in February 2022.

More recently, the auction of two offshore wind energy area leases off the mid-Atlantic coast in August of this year generated rates of $739 and $100 per acre.

Aubrey Ellertson Church, policy manager for the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance, called the sale price “disappointing.” A low sale price affects the fisheries compensation funds, initially set at 12.5 percent of the total sale price of the lease. Compared to other lease sales, the compensation generated by a $50-per-acre sale “just doesn’t seem equitable,” Church said.

But the $2.7 million allocated in the lease sale is not a ceiling for compensation. Church said she hopes that the value of the compensation fund will increase once BOEM conducts its environmental impact assessment and determines the fisheries value that will be lost in this development.

BOEM has acknowledged previously that wind development may affect fisheries access, and the agency has excluded key fishing grounds like Lobster Management Area 1 from the Gulf of Maine lease areas. But whether certain fisheries will lose access will likely be based on the type of gear being used, Church said. Because the floating turbines will be anchored to the seabed by cables, mobile gear, like bottom trawls and dredges, will likely be excluded in the areas altogether.

More stationary fishing techniques, like lobster pots and rod and reel fishing, may not be as affected, Church said. But she said that construction activity might require temporary vessel-free buffer zones, and that operational wind farms present navigation and safety concerns because of radar interference and collision risk.

Church also said that she is hoping that wind companies don’t simply “check the box” when it comes to communicating with the fishing community. She thinks fishermen can provide valuable input on the placement of turbines and anchoring sites to make fishing in these areas safer.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on Nov. 7, incorrectly reported that total revenue from fishing in the three Massachusetts wind lease areas that were sold was $3,462,000 in 2022. The correct amount was $3,523,000.