The Englishman E.M. Forster (1879-1970) wrote six novels and published five of these between 1905 and 1924. Best known and loved are A Room With a View, Howards End, and A Passage to India. In each of these novels, Forster explored psychological and political tensions related to sex, race, gender, and class. His compelling characters and their emotional dilemmas have kept the novels fresh for generations of readers, even inspiring film adaptations.

The one novel Forster chose not to publish in his lifetime was Maurice, which he wrote in 1913 and 1914. In this work alone, Forster explored the inner life of a male character who slowly grows aware of his sexual attraction to men. Forster, like Maurice, was gay and struggled to understand and accept himself. He kept his sexuality private, fearing professional and legal repercussions.

Forster wondered, in this novel, what it might be like to make a different choice. He cast Maurice as a person in every way comfortable and average except in his sexual desires. This characterization allowed him to plumb the depths of a person not particularly well suited to introspection.

“A slow nature such as Maurice’s appears insensitive, for it needs time even to feel,” Forster wrote in the novel. “Its instinct is to assume that nothing either for good or evil has happened, and to resist the invader. Once gripped, it feels acutely, and its sensations in love are particularly profound. Given time, it can know and impart ecstasy; given time, it can sink to the heart of Hell.”

Unprotected against the deep feelings love inspires, Maurice falls hard for Clive, a fellow student at Cambridge. Their relationship lasts three years and is never sexually fulfilled. Clive declares that he has “become normal,” finding himself attracted to women and choosing to marry. Maurice is devastated and profoundly lonely. He seeks a cure from a hypnotist, asking, “What’s the name of my trouble? Has it one?” The hypnotist replies: “Congenital homosexuality.” This is the first time Maurice — and Forster’s readers — can name his condition and appreciate the legal obstacles preventing men from being part of a couple in England.

Forster refused to end this uneven but intriguing novel as a tragedy. Near the end, he introduced Alec, a game keeper working at Clive’s estate. Maurice and Alec catch one another’s eye, have sex, and — after a bit of melodrama involving missed telegrams and a ship’s departure — decide to live together.

Forster wrote a “terminal note” to follow the novel. In it, he defended several of his narrative choices and expressed dissatisfaction with the ending. He reported that friends who had read the manuscript encouraged him “to write an epilogue,” but he was unhappy with his attempts. Besides, he wrote, “Epilogues are for Tolstoy.” He left the novel as he had crafted it, choosing not to bring his characters “into the transformed England of the First World War.”

William di Canzio is undeterred by Forster’s misgivings. With his new novel, Alec, published in July by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, di Canzio re-imagines Maurice through the eyes of Forster’s gamekeeper.

Di Canzio begins with Alec’s birth and schooling, setting him on a path to encounter Maurice at Clive’s estate. Di Canzio shows Alec knowing from an early age, as he encounters images of Greek and Roman gods, that “Their nudity thrilled him. … His heart would pound while he gazed; his face would flush… He wanted to live in that world, to be one of those athletes, to run naked and grapple — admire, be admired — to love.” Unlike Maurice, Alec isn’t ashamed of his desires, though he realizes they will elicit anger from his family.

Unfortunately, di Canzio spends the first hundred pages of his novel covering plot points Forster explored in Maurice. As Forster predicted, the only way forward in time places the lovers in the middle of World War I. Alec and Maurice enlist with the intention of serving together, but rigid class divisions send them down different paths. Di Canzio reunites the two, telescoping their advancing years in the final sections of the book.

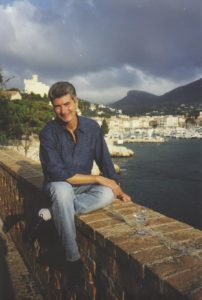

Di Canzio, a Philadelphia-based playwright and writing teacher, must have been inspired at least partly by personal experience. He had been an active member of a Catholic community for 35 years when he married his long-time male partner. Their abbot requested a meeting to inform di Canzio that, as a consequence of the marriage, di Canzio and his husband would no longer be allowed to serve as lay leaders in their parish.

Writing of the meeting in the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2017, di Canzio declared that his “sexual nature, like that of all human beings, is holy; my marriage is a sacrament where I encounter the love of God every day.” By building up and out of Maurice, di Canzio applies his philosophy to two lusty characters whose sexual encounters are frank, positive, and energetic.

Di Canzio struggles to write compellingly in other areas. His description of a female character struggling with her husband’s longing for men, for example, is inexcusably bad. Di Canzio shows her getting herself in the mood for sex (for procreation) by conjuring images of her husband’s “strong hands at last month’s birthing of the lambs.” Baaaaa. Or: ewe.

Di Canzio’s writing — from dialogue to descriptions of emotional states — is often clunky, and he can’t quite pull off an inclination to mix old and new. To bring his novel into the era of the First World War, di Canzio mentions French poets Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud, drops in medical references to Spanish flu and trench foot, incorporates battle and geographic names (Gallipoli, the Somme), and places Alec alongside characters belonging to London’s bohemian Bloomsbury Set and Paris’s famed brothel, Le Chabanais. These references mostly land with thuds. I found di Canzio’s decision to adopt modern terms such as “queer” and “hard-on” jarring. They further distanced me from the time period he was trying to invoke.

In short, Alec often reads like a screenplay, with shorthand descriptions for costume and set designers. Perhaps a Hollywood studio will option the novel and produce a queer-positive, feature-length film to good effect. As a novel, meanwhile, Alec cannot compete for psychological insight and historically accurate description with the likes of Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy. Neither can it compare favorably to Forster at his best. But for a bawdy, escapist beach read as the Delta variant sends us all into a panic? Why the heck not?