It was “The End of Piracy,” wrote Cotton Mather, the Puritan minister, owner of enslaved people, revolutionary, and witch-hunter who is often called the “grandfather of Evangelicalism,” in a 1717 pamphlet.

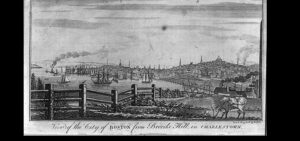

The ship of Black Sam Bellamy had foundered just offshore of Wellfleet that spring, and Mather had given last rites to the last of his crew. Six pirates were executed under Mather’s watchful eye on Nov. 15, 1717, while two were found innocent in Boston courtrooms.

There was a ninth survivor, a 16-year-old Native American named John Julian, who was not given a trial and was likely sold into slavery.

According to court records, those nine were the only pirates out of more than 130 members of Bellamy’s crew to survive the wreck of his recently commandeered slave ship, the Whydah, and the smaller boat it had just captured off Nantucket, the Mary Anne.

Mather’s pamphlet includes a long reconstruction of the conversations he held with the pirates as they rowed across Boston Harbor to be executed in Charlestown. Along with their statements at trial, they are the last words on record from the men of Bellamy’s feared crew.

An April Storm

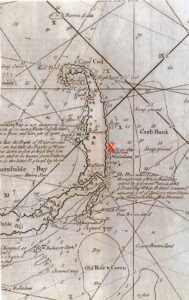

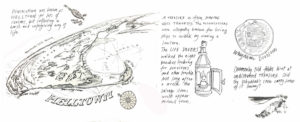

On the evening of April 26, 1717, Bellamy was aboard the Whydah, named for a slave trading region on the coast of Africa in what is now Benin. He was sailing behind the Mary Anne, which he had commandeered that morning.

The waters along the eastern shore of Cape Cod were notoriously dangerous, and Bellamy needed someone familiar with the area to help him navigate northward. Bellamy put seven of his pirates on the Mary Anne to watch over three of its original crew: Thomas Fitzgerald, the mate, James Dunavan, the captain’s brother-in-law, and Alexander Mackonachy, the cook. The boat’s captain, Andrew Crumpstey, and the rest of his crew were taken aboard the Whydah as prisoners.

The Mary Anne’s crew apparently tried to subvert Bellamy’s orders. In his courtroom deposition, Dunavan mentions that Mackonachy, who took the helm, at one point tried to steer the ship off course; a pirate named John Baker threatened to shoot him in the head. The three prisoners were made to keep the ship sailing north while the seven pirates partook of its liquor supply.

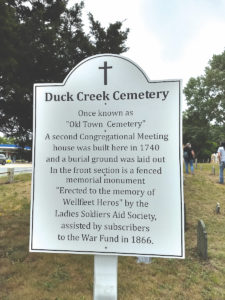

The storm was too much for the Mary Anne, though, and it was wrecked around 10:30 p.m. near a now-sunken island off Chatham with the unfortunate name of Slut’s Bush. The Whydah made it as far as Wellfleet before running aground on a sandbar around midnight and capsizing in the violent storm.

Cape Cod folklore holds that the crew of the Mary Anne intentionally wrecked their ship. Levi Whitman reports the same in a 1794 history of Wellfleet written for the Massachusetts Historical Society; he incorrectly wrote that Crumpstey was still piloting the Mary Anne when it sank, however, making the rest of his testimony dubious.

Henry David Thoreau, in his 1865 travel memoir Cape Cod, offers an even more exciting account of the wreck: while the seven pirates on board the Mary Anne slept, he writes, the three captured crewmen “threw over a burning tar-barrel in the night, which drifted ashore, and the pirates followed it.” The detail of Mackonachy’s errant steering had evolved over the years into an exciting tale of high-seas betrayal.

Regardless of whether the crew of the Mary Anne intended to wreck it, the capsizing of the Whydah killed nearly everyone on board, pirate and prisoner alike.

The only survivors were Thomas Davis, a ship’s carpenter who had been captured by Bellamy five months before the wreck, and John Julian, who at 16 was already a pilot and navigator. They came ashore in Wellfleet and stumbled to the house of one Samuel Harding, who gave them shelter and then went to the beach to search for valuables.

All 10 people on the Mary Anne survived the night and made it to Slut’s Bush in the morning, from which they were rescued a few hours later and brought to the mainland.

The End of Piracy

The seven pirates were now in danger, and they demanded that Fitzgerald pretend they were his crew. The ruse was short-lived, however; Mackonachy reported them to the authorities, and all seven were in Barnstable County Jail by nightfall. Davis, who had come ashore from the Whydah in Wellfleet, was in jail by April 29.

Eastham magistrate Joseph Doane wrote a letter to Lt. Gov. William Dummer about the arrests, but it makes almost no mention of John Julian, the other survivor from the Whydah. Court records indicate that Julian was a Native American, which is probably why he was not given a trial in Boston. Based on artifacts uncovered at the wreck, most Whydah researchers believe he was from the Mosquito Coast of Central America and of mixed African and Native descent.

According to National Geographic, Julian was probably among Bellamy’s earliest crew. He could have been freed from a slave ship or met Bellamy during his travels in and around Nicaragua.

Davis, the captured carpenter, told the magistrates in Boston that Bellamy divided treasure evenly among all his men, many of whom were former slaves. It’s likely that Julian was treated as an equal during his time as a pirate.

That ended in Massachusetts. A 1999 National Geographic article says that John Julian was probably the same “Julian the Indian” later recorded as a slave of John Quincy, grandfather of President John Quincy Adams.

If that is so, then re-enslavement was not the worst that Massachusetts had in store for him: “Julian the Indian” was executed in 1733 for escaping enslavement and then killing his bounty hunter.

Six months after the wreck, in October 1717, the other eight pirates stood trial in Boston. Nearly all of them claimed to have been coerced by Bellamy into a life of crime. The only exception was John Shuan, who said he joined Bellamy’s crew because he needed a doctor. (Shuan, who was French, didn’t speak English very well and often failed to understand what courtroom officials were asking him.)

Two of the eight pirates were acquitted. Thomas South, one of the seven that Bellamy stationed aboard the Mary Anne, was described as civil and polite by the three crew from that ship who survived, and one said that South had confided a desire to escape from Bellamy.

Davis, the recently captured carpenter, also told the court he had frequently asked Bellamy to be released. Sailors who had crossed paths with Bellamy’s crew confirmed Davis’s testimony, adding that the pirates had voted to keep him aboard on pain of death or torture. Davis fell to his knees and thanked the court when he was determined to be innocent.

The seven pirates aboard the Mary Anne appear to have all been religious. Fitzgerald, the Mary Anne’s mate, testified that the pirates made him read aloud from the Book of Common Prayer while the storm was destroying the ship.

The six convicted pirates — John Shuan, John Brown, Thomas Baker, Henrick Quinter, Simon Van Voorst, and Peter Cornelius Hooff — were led in prayer by Cotton Mather during their row to the gallows.

Quinter, Baker, and Hooff repented of their crimes “distinguishingly” before their deaths, Mather wrote. Brown cursed mightily in his last moments, while Van Voorst continued to maintain that he had been coerced into misdeeds and was not guilty. Shuan did not understand the prayers he was supposed to repeat but thanked Mather anyway.

Just before their deaths, Mather wrote, Boston minister Benjamin Wadsworth delivered a fiery benediction: “That the Pirates now infesting the Seas may have a Remarkable Blast from Heaven following them,” Wadsworth prayed. May these “Sea-monsters, of all the most cruel, be Extinguished.”

Less than two weeks after the execution, however, the French slave ship La Concorde was captured off the coast of Saint Vincent by a man who had previously sailed with Bellamy. The captor, who renamed his prize Queen Anne’s Revenge, was named Edward Teach. History knows him better as Blackbeard.

“I was raised in New Bedford,” Dr. Silva tells me as she swipes her hand through the water in the tank. “My father — they called him ‘High-Line’ — captained scallopers for close to 40 years. I started fishing with him in the summers when I was 16, and when I finished high school I went at it full-time.”

“I was raised in New Bedford,” Dr. Silva tells me as she swipes her hand through the water in the tank. “My father — they called him ‘High-Line’ — captained scallopers for close to 40 years. I started fishing with him in the summers when I was 16, and when I finished high school I went at it full-time.” A story does not have to be old to constitute folklore. Among three of the most frequently told stories, two date back hundreds of years, and one is more modern.

A story does not have to be old to constitute folklore. Among three of the most frequently told stories, two date back hundreds of years, and one is more modern.