Even if you are not the kind to frequent galleries, you’ve seen Jackson Lambert’s art. He worked with Anton “Napi” Van Dereck Haunstrup, making the paintings, sculptures, and signs that decorated Napi’s Restaurant on Freeman Street — including the original eye-of-Horus emblem that became its logo.

Lambert, who was born in Indiana in 1919 and grew up in Illinois, had visited and studied art in Provincetown since the 1930s but didn’t move to town to stay until 1966. His best friend, Frank D. Schaefer, had come to visit in 1962 and a year later, according to David W. Dunlap in Building Provincetown, Schaefer bought the building at 500 Commercial St. and set about creating the White Horse Inn. Its walls were gradually covered with Lambert’s paintings, signs, and sculptures.

Dunlap lists some of “a stellar cast of transients” who stayed at the inn over the years: Norman Mailer, Joyce Carol Oates, Grace Paley, Gore Vidal, and John Waters. After Schaefer died in 2007, his wife, Mary Martin-Schaefer, kept the 18-room inn going until last year. “Alas, after more than sixty summers and sixty winters, the time has come to close its doors,” she wrote on the inn’s website.

Martin-Schaefer sold the 200-year-old inn at Daggett Lane and Commercial Street in October 2023 and now has decided to sell a fleet of Lambert’s paintings and found-object sculptures through Bakker Auctions. His oil painting of the snow-capped White Horse Inn sold for $1,600 at Bakker’s June 1 auction. An exhibition of other works will open July 12 and run through July 28 at the Bakker Gallery, 359 Commercial St., on the alley across from the Provincetown library.

Gallery and auction house owner Jim Bakker said Lambert’s work in Napi’s Restaurant is part of the Van Dereck Haunstrup estate and will not be included in the show.

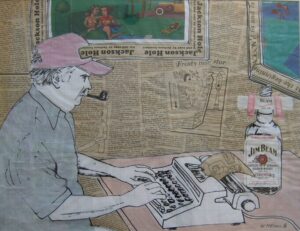

Lambert’s work is funky, absurd, blunt, and impossible to pin down. He worked across mediums: he’s known for his abstract paintings, newspaper illustrations, and room-filling installations (not to mention for the column “Jackson Hole,” which he wrote for four decades, first in the Provincetown Advocate and later in the Provincetown Banner). Sometimes he would sign his work using a different name — teasing the viewer in the service of play.

In Faithfully Yours, David Burpee, a portrait-over-found-object construction, Lambert paints a tongue-in-cheek homage to the seedsman and president of the world’s largest seed seller at the time, the W.A. Burpee Co. Found-wood objects from the dump are assembled and attached to the bottom of a portrait of Burpee, who is surrounded by obscenely bright flowers. The shape of the portrait, an upward triangle, with the assembled objects underneath it resembles a shrine.

by Jackson Lambert.

“He’s probably the most underrated Provincetown artist we’ve got,” says painter and printmaker Bill Evaul. “He could speak several languages of paint. He loved matchbook ads. He remained independent even though he was friendly with the guys he thought of as stuffed shirts.”

Evaul was 21 in 1970 and a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center when he first met Lambert. At that time, Lambert and his wife, Carmen Felt, lived in a cottage behind Napi’s Restaurant.

Lambert was busy then building “total wood-environment studio apartments” with found objects, driftwood, and dump pickings. “Back then there was no transfer station, just a dump,” Evaul says, “and he’d go out and pick and find parts, even beams.”

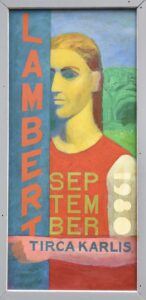

Instead of seeking gallery representation, Lambert worked with art dealer Lynne Burns in New York. He was constantly working, Evaul says, and he found ways for his pieces to be shown. In Tirca Karlis (1980), Lambert has turned the late Provincetown gallerist’s sign into a painting. The piece features his adventurous color choices, subtle humor, and surreal figurative work. Rather than the painting being a sign itself, the painting is of a figure holding a sign for the show. The steel blue shadow across the figure’s eyes freeze her in place. Lambert places the lettering in such a way as to require a tilt of the head from the viewer.

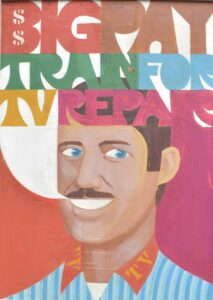

In Big Pay Train for TV Repair, Lambert paints a handsome fresh-shaven man in a robin’s egg blue and powder blue striped shirt with the letters “TV” painted on his collar in burnt orange. The man is stuck in his own smile, where an empty white thought bubble has occupied his mouth.

In Foot Long, undated (est. 1960s), Lambert paints Lopes Square in warm weather, but there are no people on the street. Buildings are empty; signs for Foot Long Hot Dogs, Coca-Cola, Ice Cream, Home Made Fudge, and Salt Water Taffy run across the building but play to no audience. Olympic blue windows hold us in suspense: Is it morning? Is the town hung over?

When Lambert moved to Provincetown in earnest in 1966 he was with Felt, a former nightclub dancer and artist in her own right. The pair had a tumultuous relationship. “I went out for a loaf of bread and was gone for two years,” Dunlap has Lambert telling Sally Rose in a 2009 interview in the Banner. The couple bought a house at 150 Commercial St. in 1974.

Mary Martin-Schaefer recalls a time Lambert sold a map of the town to the chamber of commerce. But on it there were only two addresses: that of the White Horse Inn at 500 Commercial St. and number 150, which was Lambert’s house.

According to Evaul, Van Dereck built Lambert a little apartment across from Napi’s when Lambert and Felt were in dire straits. “That little building across from the restaurant set back from the house on the corner was his spot,” says Evaul.

Behind the house at 150 Commercial St. “there was a Siberian elm tree that had come down in a hurricane,” says Evaul. “Lambert cut it up, took the trunks and limbs, and glued them back together. It had no leaves and no branches, no canopy. It was a free-standing sculpture.”