NEW BEDFORD — The whaling museum here celebrates bigness. Two whale skeletons hang from the lobby ceiling. The centerpiece of the museum is a three-story replica of the whaling vessel Lagoda, billed as the largest model ship in the world. There’s a replica of a whale’s heart so large you can walk through it.

But as you turn into a small gallery off the walkway above the Lagoda, that feeling of scale falls away. The ceiling is low, and the carpet dampens the sounds of the museum. On the walls hang sheets of paper with black stamps in the shape of whales, images that recall a cemetery. In a sense, it is: each black-and-white work commemorates a real whale stranding.

Artist Daniel Ranalli, who lives in Wellfleet, was sitting in a café on Sept. 10, 1991 when he heard people talking about a commotion at Chipman’s Cove. Apparently, a pod of whales had beached themselves. He drove down to the cove and found them — 24 pilot whales. Soon, rescuers arrived to keep the animals alive until the tide came back in. They were able to save 21 of them.

“Going next to them and watching their eyes follow you,” says Ranalli, “you knew that this was a sentient creature.”

Ranalli began researching strandings and was struck by how our attitudes toward these events have changed. “In the beginning,” he says, a stranding “was manna from heaven.” A single beached whale could provide oil, blubber, and meat to the lucky harvesters, while a stranded pod could provide goods to sell for a whole town.

Today, there are teams for keeping lost, entangled, or stranded whales alive. Ranalli finds a fascinating irony in this change. We have “this history of killing this animal almost to extinction, but now we’re saving them,” he says.

Inspired by his own experience and his historical research, Ranalli created a tribute to the beached whales that has culminated in Whale Stranding, an exhibition on view at the New Bedford Whaling Museum until February 2024.

Ranalli’s monoprints, each of which depicts a particular stranding, consist of cotton paper stamped with whale-shaped woodblocks, one for each stranded animal in that event. Ranalli sometimes styled the paper by printing pages from the journal of a whaling ship.

Below the print, Ranalli wrote the date, location, and number of whales involved in the stranding, as well as the weather at the time if he could find it. The strandings span space and time. Eight pilot whales, Java, Indonesia, 2016. Four Cuvier’s beaked whales, Duguy, France, 1974. One finback whale, Eastham, Mass., 2009. Despite the fact that the works are abstract prints, the stranded whales feel strangely tangible.

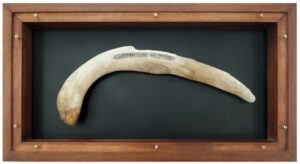

Ranalli describes whaling journals as “the architecture” of his work. Captains in the 19th century, the heyday of New England whaling, kept journals of their voyages, and they would press whale-shaped stamps in the margins of this book, with a little square in the middle to write how many barrels of oil they harvested. Ranalli’s prints use this same visual language to depict strandings instead of hunts. By tying the two together, he seems to ask: how responsible are we for these whales that wash up on shore?

The science behind whale strandings remains unclear. As an essay in the exhibit’s program by Robert Rocha, the museum’s associate curator of science and research, explains, theories abound: whales getting trapped by outgoing tides, herd mentality, disease, underwater earthquakes, and the shape of the shoreline.

Some strandings, however, are directly tied to human activity. Sonar messes with a whale’s echolocation and navigation. Military and industrial activities that generate loud, high-frequency noises can drive the strandings. That was certainly the case when a U.S. military training exercise drove 17 whales to strand themselves in the Bahamas in March 2000.

Ranalli once wanted to be a scientist, he says, and science plays a role in his art. “Mapping, satellite pictures, all of those things feed my brain,” he says. “If you’re an artist, there’s only really two things you can do. You deal with how people relate to each other, or you deal with how people relate to the land.”

Placards in the exhibit explain how strandings in southern New England are changing. In 1999, only 14 percent of mass-stranded dolphins along the southern coast of Massachusetts and Cape Cod survived to return to the ocean. Thanks to improved rescue efforts, scientific understanding, and communication, that percentage rose to 75 in 2021.

Around the final corner of the exhibit, there is a massive sheet of rag paper covered with 1,405 whale stamps, giving the piece its name: 1405 Whales. It depicts the largest stranding in North American history, in Truro in 1874. A massive pod of pilot whales was likely pushed to shore by boats, then forced onto the beach. The townspeople peeled the skin off these animals and collected the blubber to turn into oil, harvesting 2,700 gallons.

The scale of the story is pushed to the forefront by this work. The enormity of the whaling industry’s destruction and the tragedy of strandings are immediately apparent. If the whole exhibit is a cemetery, this piece is a cenotaph, commemorating a singularly violent day.

Reflected in the glass encasing 1405 Whales is modern-day New Bedford Harbor. The city was built on whaling. The vibrant town here, and so many others in southern New England, would not exist were it not for the fortune extracted from these animals. Seeing this depiction of mass slaughter paired with a reflection of the region’s present-day success calls to mind how we still benefit from the deaths of these whales, even as we put so many resources into saving them today.

Rescue Effort

The event: Daniel Ranalli’s Whale Stranding

The time: Through Feb. 19, 2024

The place: New Bedford Whaling Museum, 18 Johnny Cake Hill

The cost: General admission: $22