In May 1840, a small group of sport fishermen set out from Newport, R.I. in search of sea-run brook trout. Traveling first by ferry, then by coach and horseback, and lastly by sailing yacht, they headed for the Holy Grail of salter brook trout fishing: the Mashpee River.

In an article published the following summer in New York City’s earliest sporting publication, Spirit of the Times, the author (identified only as “S.T.T.”) described the group’s fishing successes — they caught trout, using worms, minnows, and hand-tied flies, in every stream they passed.

At the Mashpee, they landed 35 salters in their first few hours of fishing and in subsequent days caught 90 chrome-colored sea-run trout, each weighing from one-half to two-and-a-half pounds.

Fishermen typically did not venture farther east, as that would have required days of dangerous sailing around Race Point to get to the mouth of Fresh Brook. But when the railroad reached Wellfleet 30 years later, Fresh Brook became a significant sporting destination, attracting fishermen including, by some accounts, former U.S. President Grover Cleveland.

By the middle of the 20th century, the Cape Cod rivers fished in that 1840 expedition had lost all, or nearly all, of their native salters.

In virtually every case, their demise was due to habitat loss from development and, in some cases, poor fisheries management, which included stocking our streams with large, voracious brown trout, which decimated native salter populations. Up Cape, the salters’ worst enemy was cranberry farming, where pesticide use combined with deployment of water-pinching dams were the problem. At Fresh Brook in Wellfleet, the culprits were the construction of Route 6 in 1948 and then the rail trail in 1953. In both cases, as a story recently published in this newspaper describes, poorly conceived culverts reduced tidal flow to leave the brook stagnant.

Now, with the efforts of fishermen, government fisheries staff, native tribes, local towns, Cape Cod National Seashore scientists, and an army of volunteers, many of the Cape’s salter streams are being restored. Fresh Brook is poised to be the next Cape Cod stream to recover its once-famous fish.

Although the push to bring back the brook is only just coming into view, the cause is one that many people have devoted themselves to over the years. The late Mike Hopper, an enthusiastic fisherman and former shellfish grant owner who spent his high school years in Wellfleet, was one of them. Hopper teamed up with Geof Day and Warren Winders of Trout Unlimited to form the Sea-Run Brook Trout Coalition, which, though based in Newburyport, won a grant in 2017 to conduct a hydrological study that helped confirm the Wellfleet project’s viability.

Another person who has played a critical role in Fresh Brook restoration is biologist Steve Hurley, who recently retired as southeast director of MassWildlife. A student of salters for half a century, he is impressed by their persistence and resiliency. “All they need is cold, clean moving water and access to the sea,” he says. “These salters are tenacious. They always find a way of holding on.”

For the trout, access to both fresh and salt water is paramount. But they also need deep pools to provide shelter and forage, clean gravel bottoms for spawning, and shade trees to prevent the water from overheating. Salters, like all trout, can thrive only in water below 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Fresh Brook’s headwaters, like most Cape springs, emerge from the ground between 50 and 55 degrees all year round, but the brook’s now-trapped water can measure 80 degrees in summer.

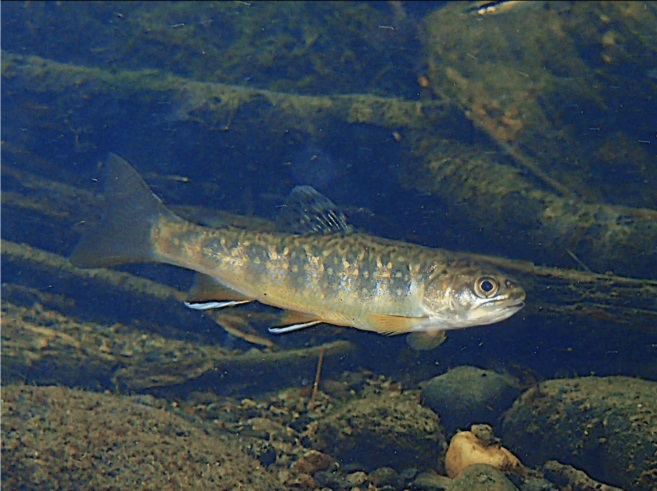

Spawning takes place in the mid- to late fall. Like all oceangoing trout and salmon, salters have a distinct silvery color. When they return to fresh water, they regain some of the brilliant orange, yellow, and blue dots, blood-red chests, and orange pectoral fins they had as freshwater brookies. Males grow a small hook, or kype, at the tip of the lower jaw. Females use their tails to dig shallow gravel nests called redds.

Over the winter, the sea trout’s fertilized eggs become alevins, hatched trout with yolk sacks still attached. These remain in the gravel until they emerge as fry — this is the fish’s most vulnerable stage. Several months later, fry begin developing vertical black stripes and enter their parr stage. It’s at this point that salters begin differentiating from typical brook trout.

While all salters are brook trout, not all brook trout are salters. A 2012 study supported by the trout coalition showed that, while all salter chromosomes are nearly identical, salters from different streams have distinct genetic markers identifying them as subspecies. Why some become salters and others do not isn’t fully understood, however.

What we do know is that successfully restoring lost salter populations is dependent on finding subspecies with DNA as close as possible to a watershed’s original fish. The most successful restorations have used native salters taken from neighboring streams, not hatchery-bred fry. Fortunately, Fresh Brook is not far from streams with brood salters similar to its original population.

In a year, parrs lose their stripes and become juveniles, or smolt. At this stage they are five or six inches long and can move out of fresh water to find better dining in tidal zones. In this phase, brookies with salter genetics modify their gills to survive in salt water. This is also when they begin displaying their protective chrome coloration.

The quality and quantity of food salters find at sea enables them to grow quickly. One returning specimen, tagged at Red Brook in Wareham in November at 12 inches, had grown to 16 inches by April, according to Winders, who is now a member of the Cape Cod Chapter of Trout Unlimited.

Cape Cod salters typically reach a top size of two pounds. They live relatively short lives of three to four years, though in some non-Cape streams, salters live as long as a decade and grow to four or five pounds. The better a salter’s habitat, the bigger and more prolific it will become.

Fran Smith, another member of Trout Unlimited, says that degradation of coastal sea bottoms is limiting Cape salters’ size and longevity. Higher nitrogen levels and damaging fishing techniques have been destroying Cape Cod Bay’s once-lush eelgrass beds, drastically reducing shrimp, mummichog, and killifish — the salter’s food supply. A large salter specimen from the mid-1800s, preserved in Harvard University’s Comparative Biology Museum, provides evidence of Smith’s theory.

No matter how long or short a salter’s lifespan, two of its characteristics have gotten fishermen’s attention: these fish are extremely prolific breeders, which explains their persistence in Fresh Brook for years after the river’s flow was restricted last century; and as sport fish they are nothing short of magnificent. Not only do they fight extremely well but they are also elusive targets for fly fishermen casting for them in narrow, log-filled streams surrounded by dense vegetation.

Still, those who have successfully restored other salter streams know that a lot more is needed to bring these fish back than simply restoring Fresh Brook’s two-way flow. Smith and others will have to find appropriate breeder fish. Then, as always, things will take their time.