WELLFLEET — On Tuesday evenings in February and March, nine Wellfleet citizens — and one Independent reporter — attended the citizens’ police academy at Wellfleet Police Dept. headquarters on Gross Hill Road.

For three hours, officers led lessons and simulations on police functions, including use of force, strategy, and compliance tools such as tasers and BOLA wraps. The curriculum was modeled on the 800 hours of training every police officer goes through, said Det. Nick Daley, who led the class with Sgt. Paul Clark.

The purpose of the academy was to “create a stronger partnership between the police dept. and citizens of Wellfleet,” according to the course packet. The purpose was not “to train its students to become police officers,” the document said.

During the first class, Chief Michael Hurley said he hoped to demonstrate “what we do, how we do it, and why we do it. In our society and across the country, there are a lot of questions about policing,” he added. “We want you to ask them.”

Participants who spoke to the Independent said they had positive views of the police before going to the class and that the class affirmed those beliefs.

“I am a law-and-order guy,” said participant George Zebrowski, who for many years after college wrote for a Springfield newspaper and was “stuck on the late-night police beat,” which allowed him to develop positive relationships with local police, he said. “I feel strongly that police are getting a bad rap nationwide.”

Bonnie and Will Tegen, who are new to Wellfleet, said they participated in the class “to know what the police are involved with, and who our policemen are,” Bonnie said. Will said that “many people paint poor pictures of the police when they don’t know what really goes on.”

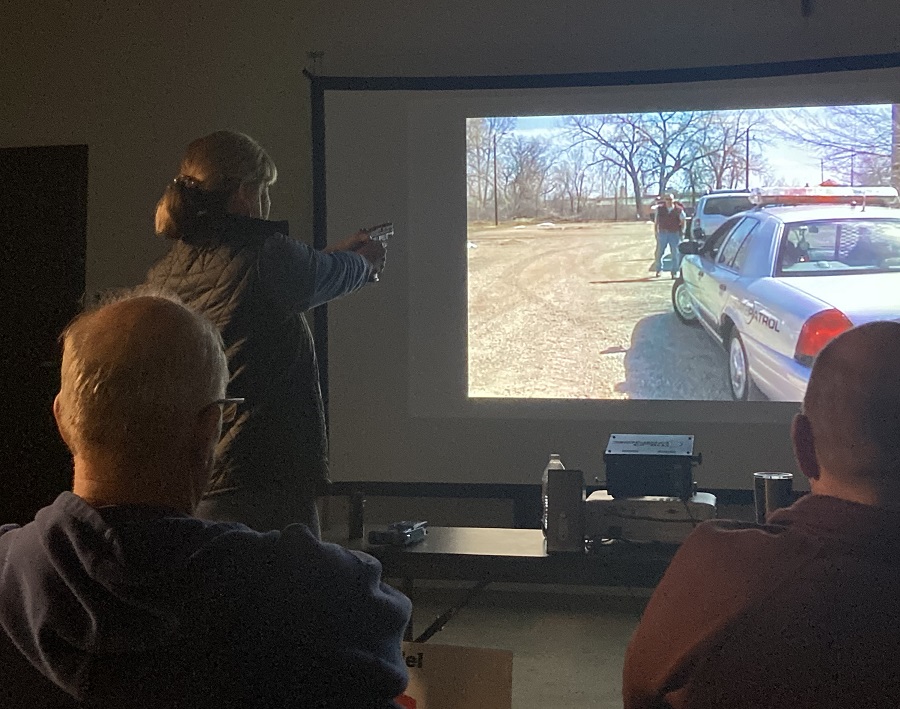

Participants identified a March 21 lesson on use of force and firearms as “a real eye-opener,” Zebrowski said.

During the class, students took part in a simulation that calibrated potential risk in fictional scenarios against the level of force officers are meant to respond with. Participants were offered the choice of using a toy gun or a Glock pistol retrofitted to fire carbon dioxide cartridges. All participants chose the toy gun.

In virtual scenarios of armed robberies, domestic disturbances, and suicides, citizens were tasked with deciding which weapon to respond with based on a model that matched perceived threat with reasonable response. According to the model, a compliant subject should be met with cooperative controls, whereas an assaultive subject should be met with either defensive tactics or deadly force.

“There are a lot of factors that go into an officer’s decision to use force,” said Sgt. Kevan Spoor of Provincetown, who led the workshop. “Officers have to make decisions in split seconds. One of the biggest obstacles police across the country are facing today is that we are not using force enough because of mainstream opinions. No officer wants to be the next one on the news. We are seeing a lot more inaction than action.”

Spoor added that “the news would like to portray the police in a certain way, like people are getting killed by police every day. It’s not that way.”

According to the research group Mapping Police Violence, there have been six days so far in 2023 when police did not kill someone in the U.S.

Spoor said that 246 officers were killed in the line of duty in 2022, and 44 officers have died this year, according to the Officer Down Memorial Page.

Mapping Police Violence lists 1,238 people killed by police in 2022, and 301 killed so far this year.

The Wellfeet police respond with force two to five times per year, and “most of that is low-level force,” according to Hurley. Daley said no officer has discharged a gun during his time at the department, which began in 2015.

Students learned about the use of body cameras, tasers, and BOLA wraps. Wellfleet’s was the first town police department on the Cape to adopt body cameras, in 2022. There are still only three departments with cameras: Wellfleet, Mashpee, and Yarmouth.

Hurley said the goal of the cameras is “transparency and documentation.” He said that the cost of body cameras is the biggest obstacle for departments that still don’t have them.

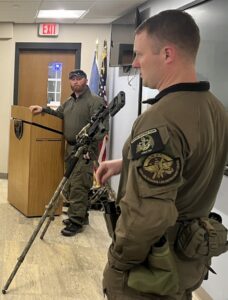

Sgt. Jeremiah Valli demonstrated the use of tasers, which, he said, “changed the face of law enforcement.” By means of neuromuscular interruption, the subject is briefly incapacitated, during which “your eyes flutter, you scream, and your body freezes, causing violent muscle contractions,” Valli said. “Can people be killed with tasers? Yes, it has happened, but it has never happened here.”

Reuters has documented at least 1,081 deaths from tasers since police departments adopted them in the early 2000s.

Hurley said Wellfleet adopted a new technology last summer called BOLA wraps. They discharge seven-foot Kevlar cords that wrap around a noncompliant subject and are a nonviolent alternative to tasers and pepper spray, said Off. Ed Garneau.

“It’s an important tool that does not achieve compliance through pain,” Garneau said. He added that Wellfleet is one of few departments on the Cape that uses them.

The four most common crimes the Wellfleet police deal with, according to Clark, are operating under the influence, disturbing the peace, disorderly conduct, and assault and battery.

Daley said that “almost all of the emergency calls we get deal with mental health in some respect. As police officers, we are held to a higher standard. We are held under a microscope.”

“We take the uniform off,” Officer Laecio De Oliveira said, “but we are still cops wherever we go.”