Jody Johnson is one of those rare people you can turn to when things fall apart. Last February, she was one of the stars of the Wellfleet Fix-It Clinic, saving the day for helpless locals who stood in line with wires dangling around their ankles, bearing an array of no-longer-functioning gadgets.

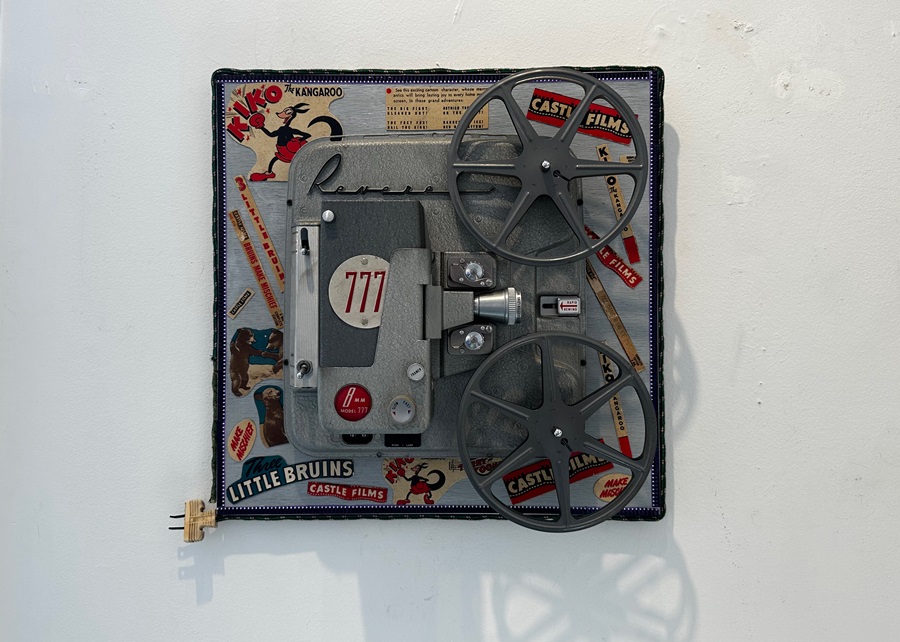

Today she is in her blue overalls repositioning her work — a series of lamps and assemblages made from vintage projectors and their parts — in the Urvashi Vaid and Kate Clinton Room at the Provincetown Commons in preparation for her show, “8mm.” The projectors date from the 1930s to the 1970s. Manuals and electric cords frame the pieces.

“I’ve always had a passion for taking things apart,” says Johnson, who has been making lamps for 20 years.

Johnson zips around the Cape in Skully, a 1997 Honda hatchback that has 297,000 miles on it, looking for castoffs she can repurpose. She bought the car from a friend who left a skull sticker on the inside of the driver’s side door. Johnson’s “mechanical beauties” have been found at Goodwill, Salvation Army, churches, estate sales, and thrift shops. She pulls over when she sees an innkeeper tossing something in the trash: “You giving that away?” she asks. She buys nothing online. She cleans every item she brings home thoroughly, using steel wool, wet sand, and a lot of elbow grease.

For one of her lamps, Johnson used a 1930s Bell & Howell 8mm film projector. She cut down the case and cleaned it up to create the lamp’s base. Johnson chose a burlap shade because it picks up the texture of the case. She found the neck of the lamp at the dump and selected it for this piece because it has a similar tone and texture — she looks to integrate the disparate elements of each finished piece.

“There’s a lot of work that goes into them that people don’t see,” Johnson says. She stays away from power tools and prefers working by hand. As she takes her finds apart, some parts come away with a screwdriver or wrench, but sometimes she has to use a hacksaw. She catalogs the parts with her camera. Reassembling them into her own pieces, she aims for precision, building even, symmetrical sculptures.

Johnson grew up in New Haven and went to work right out of high school as a self-taught machinist. She got her license at 19, she says, and started working on aviation parts at Turbo Motive, an FAA repair station.

But in 2000, after getting a leukemia diagnosis and going through treatment — her brother Mark was her stem cell donor — she decided not to go back to corporate manufacturing. Mark owned a high-end lamp restoration company in Stamford, and she took a job in his service department, overseeing the mechanics while they rewired vintage chandeliers and lamps.

Her brother had clients who wanted their personal items redesigned, and he tapped her to do the work turning things like 1950s kitchen mixers into lamps. “People know me for my Easy-Bake Ovens,” she says. When Martha Stewart wanted her six-foot wagon wheel made into a chandelier, Johnson got right to it. “They had to weld a beam into her farmhouse to support the weight of this thing,” she says.

Johnson moved to Provincetown in 2008. After donating some work to a Christmas show — just some earrings and a couple of lamps, she says — she got an invitation from ceramicist Paul Wisotzky to show her work at his Blue Gallery. “I want everything you make,” he said.

Wisotzky’s gallery was in Provincetown back then, and being shown there was a formative experience for Johnson. “I feel like I owe my career to Paul,” she says. Since then, she’s shown at Woodman/Shimko Gallery, at Trove Gallery in Orleans, and at the Commons, where her current exhibition runs through Oct. 27.

Johnson wishes she lived in a simpler time. She has basic cable and an avocado-green TV from 1974. She doesn’t stream anything. She doesn’t have a smartphone, computer, or internet service.

“You ask me to fix something, and I will dive in,” she says. Johnson leaves fix-it cards at the hardware store. People call her to rewire their clocks. A friend just asked her to repoint a brick wall. “I’ll lay your bricks, I’ll fix your wall, I’ll clean your tub,” she says. “I have no shame! That’s what we have to do — it’s a privilege to live here.”

And she gets phone calls from people who want family heirlooms turned into lamps, some even coming from across the country. Johnson demands complete artistic freedom on commissioned pieces. “I say ‘commissioned,’ but they’re not,” she says. Many details, “even the choice of shade,” she says, “is mine.”

Johnson has no formal training. She doesn’t Google anything. She doesn’t sketch anything. She looks at something and sets to work.

“Once I put the thing on my bench and start pulling it apart,” she says, “I know where it’s going.”

Mechanical Beauties

The event: “8mm,” assemblages by Jody Johnson

The time: Through Oct. 27; opening Tuesday, Oct. 15, at 2 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Commons, 46 Bradford St.

The cost: Free