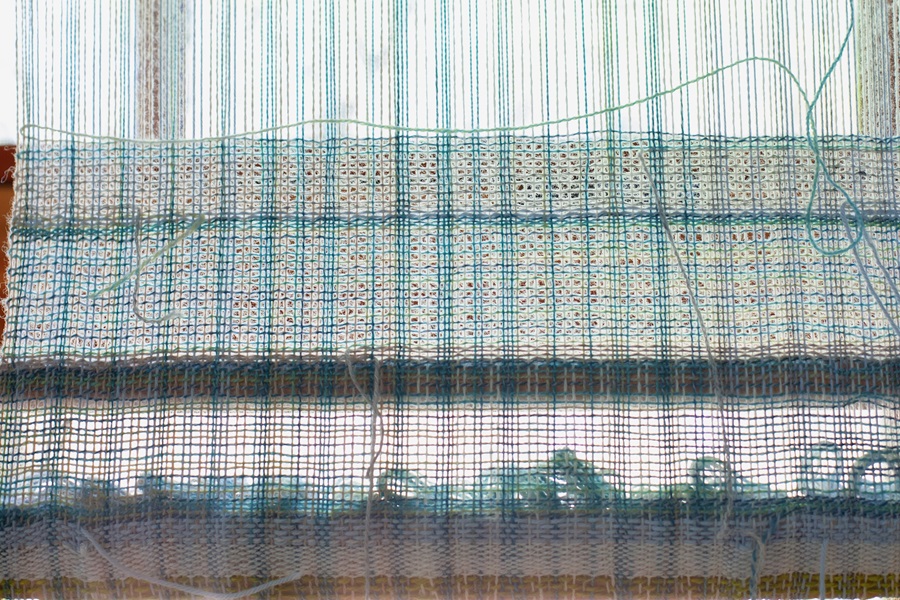

A friend had a significant birthday recently, which is to say that one day she turned a decade older than she used to be. By “recently” I mean over two years ago. I’m not trying to be imprecise — it’s just that in my decade one begins to count tectonically. Anyway, it was a birthday that warranted something special, that is, handmade and time-consuming, so I decided to make her a long, wide scarf. I’m an on-again, off-again weaver, but things like significant birthdays get me going, so I set up my very basic loom with a bunch of blues that were a riff on my friend’s eye color.

I went at it hard for about a week, and the thing looked pretty damn good, if I do say so. I don’t remember what intervened, but two years later the shawl is still on my loom, and my friend is now heading to the middle of her current decade at an alarming rate. Wherever she is, I hope she is not reading this and ruining her birthday surprise.

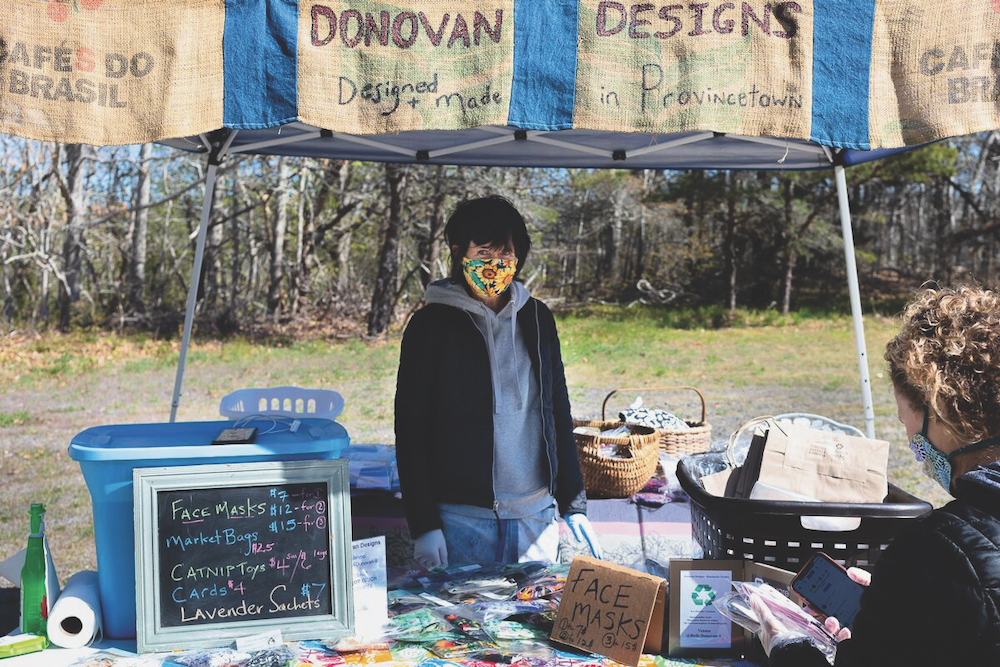

This is all to say that I probably have no business starting any new projects right now, by which I mean I have no business buying yarn. But one hazy late-summer morning at the Wellfleet Farmers Market, I wandered over to the Biltmore Wool Barn, whose sign has an intriguing logo of what seems to be an alpaca.

The wool there is gorgeous and alluring, even in the summer heat. Yarns range in thickness and texture (chunky, curly, fine) and come in an array of colors, some bright and funky, some cool and earth-toned, all hand-dyed and spun in Brewster by husband and wife Mark Stephens and Kathy Mealey. I lingered, chatting with Stephens about his triangle loom, all the while hoping the conversation wouldn’t prompt me to go home and order one.

I asked him whether alpaca was strong enough to weave with. Warp threads — the ones that go the long way — have tension on them, and not all yarns can handle it. He told me he knows a number of weavers who have used it successfully.

Stephens and Mealey have been raising alpacas for over 30 years. It all started when Mealey, a knitter, began spinning her own yarn. When you spin your own yarn, Stephens says, you have to buy fleece, and when you have to buy fleece, you end up buying sheep, and eventually alpacas, which have much more luxurious wool. Sheep, it turns out, are a gateway animal leading to alpacas.

This whole thing felt like a cautionary tale for me. Our Wellfleet place is in town. And I started to imagine what my New York Coty coop board would say when I brought up the idea of housing sheep, or alpacas, in the bedroom that used to be my son’s.

I wouldn’t need many. There were once 50 alpacas at Biltmore, but now they’re down to just two. That’s because alpacas live on average 27 years, Stephens tells me. He pauses, kindly, to let me do the math, which is this: if you’re at an age where you’re thinking about the passage of time tectonically, you have to consider who’s going to take care of the creatures you leave behind. I’m going out on a limb to say that most people don’t want to inherit an alpaca.

Their story did make me a little anxious that Biltmore Wool Barn could run out of wool before I finished the scarf that’s occupying my loom. But Stephens says they have 400 pounds of wool on hand and tells me the fleece-to-yarn ratio is one-to-one, which is to say that four hundred pounds of fiber equals four hundred pounds of yarn. Most people buy yarn by the ounce.

I tried to resist the urge to buy anything from Stephens that day, but it crossed my mind that, out of service to a fellow human being, taking some wool off his hands would be an act of generosity. And there was one skein of blue that was so perfectly smoky that I couldn’t bear to leave it behind. I could use it to finish my friend’s scarf while weaving in something of the moment.

When I got home that afternoon, there were many other things I was supposed to be doing, which is of course when the internet pulls you down and alpacas become deeply fascinating.

As a result, I can now tell you, with the confidence of a newly informed Wikipedian, that alpacas know how to set boundaries (something I am still working on). I also learned that they make a variety of sounds (humming, snorting, grumbling, clucking, screaming, screeching, and, according to a 2017 article in the Provincetown Banner, orgling). Further: alpacas spit. Wikipedia says that the word is somewhat euphemistic: “occasionally the projectile contains only air and a little saliva, although alpacas commonly bring up acidic stomach contents (generally a green grassy mix).”

I read that there are two kinds of modern alpacas, one with curly wool and one with straight wool. When I called Stephens to ask him about it, he said that he prefers the curly wool, which is produced by Suri alpacas, to the straighter wool produced by the Huacaya breed. Perhaps needless to say, the following week I bought a skein of the same smoky blue yarn in the curly variety — for texture.

I’m grateful to the alpacas of Brewster, because aside from reminding me about boundaries, they gave me a jump start on getting that shawl going again.

Once it’s off the loom and delivered to my mid-decade friend, maybe I can finally get going on the orange scarf I want to make to go with my pink coat, because orange and pink is the perfect combination, and it reminds me of those women on mopeds in India who don’t seem to feel confined to stodgy colors as they enter big number decades, and because “pink is the navy blue of India” — at least that’s what Diana Vreeland once said. One of these days I need to Google her.