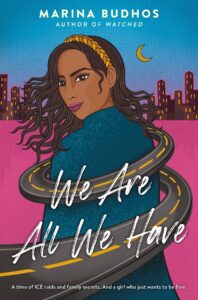

You don’t expect a book about a teenage Pakistani asylum seeker, separated from her mother by the capriciousness of U. S. immigration authorities, and an unaccompanied refugee from gang violence in Mexico to take you to Wellfleet. Neither did its author, Marina Budhos, who will be reading from and discussing her latest novel, We Are All We Have, at the Wellfleet Public Library on Tuesday, August 1.

We Are All We Have (2022) is the third of Budhos’s novels to weave classic adolescent coming-of-age themes into narratives that explore the cultural and political challenges of immigrant families from Muslim-majority countries in post-9/11 America. Though marketed as “young adult” titles, We Are All We Have and its predecessors, Watched and Ask Me No Questions, feature plots, issues, and prose compelling enough to appeal to readers of all ages.

A journalist and author of novels and historical nonfiction for adults as well, Budhos grew up in Queens, the daughter of an Indo-Caribbean immigrant father and a Jewish American mother whose own asylum-seeking parents had crossed from eastern to western Europe and finally to America.

“I’ve come to understand,” Budhos says, “that this sense of crossing over, of mixture, permeates my way of seeing the world. And it drives my writing, too. I am an adult author who crossed over into young adult; a fiction writer who frequently crosses over into nonfiction; and a writer who loves to create worlds that capture these cultural complexities.”

Budhos’s literary crossover to young adult fiction was prompted by a journalistic project that culminated in her 1998 book Remix: Conversations with Immigrant Teenagers. After 9/11, the documentary motive of Remix took on new urgency, particularly with regard to the plight of Muslim immigrants in the U. S., and Budhos conducted interviews with both documented and undocumented seekers of U.S. residency and representatives of relevant government agencies, advocacy groups, and immigrant support services.

“The journalist in me thought I was going out to get a story I wanted to report on,” she recalled, “but then the novelist in me wanted to go inside these young people’s experiences and render them on the page both for readers who might identify with them and for young American readers who might never have thought about these things.”

In We Are All We Have, a minor character speaks a line that perhaps encapsulates the central insight and organizing principle of all of Budhos’s fiction: “This country, it makes it so hard to be a family.” Budhos has confided that this sentence spoke itself in her mind before she wrote the scene in which it appears. And she believes it may resonate beyond the struggles of the kinds of binational or bicultural families, caught up in a frequently cruel and dysfunctional immigration system, that populate her novels. For even the most privileged among this generation of young people and their parents, she says, “there is an anxiety that’s humming beneath everything, and maybe it’s not an anxiety of immigration status but it is an anxiety that erodes and corrodes the capacity to just be family.”

Budhos concludes her acknowledgements at the end of We Are All We Have by thanking Wellfleet for providing “sustenance, inspiration, and family rejuvenation for years.” Though she, her husband, and their two sons regularly spend one summer week a year on the Outer Cape, her novel wasn’t supposed to go there at all. Originally entitled Sanctuary, the book set out to portray the experience of its 17-year-old protagonist, Rania, and her young brother, Kamal, who are taken in by the activist congregants of a rural synagogue after their mother is arrested in an ICE sweep of their Brooklyn apartment. But as the restless and resourceful Rania began to chafe at her confinement “under the watchful and kind eyes of the congregation,” Budhos became dissatisfied with the static setting of her novel. So, she scrapped her first draft and put Rania on the road.

“I let her lead me where it was going to go,” Budhos says. “I didn’t know it was going to go to Wellfleet.”

Finding a motivated traveling companion and hesitant first love in the street-smart Carlos, who is drawn to a painting of a lighthouse at “the edge of America” that he has seen on the internet, Rania discovers “that windswept bit of land” between Wellfleet and Provincetown offers a perfect summer refuge. There, the teenage fugitives blend in among the other young international transients who serve the Outer Cape’s tourists. Communal housing among the Czech, Bulgarian, and Macedonian J-1 visa-holders and off-the-books motel and restaurant employment allow Rania and Carlos temporarily to evade Homeland Security agents and sustain their freedom-seeking odyssey.

“Perhaps writing is often a pursuit of the Other,” Budhos muses in an essay entitled “From Village to Global Village.” But, as Walt Whitman says in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” one of Rania’s literary touchstones, self and other are intimately, inextricably bound — each of us “forever held in solution” with “the certainty of others, the life, love, sight, hearing of others.” We are, indeed, all we have. The question is how far that “we” extends and what are the costs if the answer is “not far enough.”