WELLFLEET — The town’s long-awaited targeted watershed management plan, which involves building a sewer system for the central district and applying new septic system rules to most other properties, was discussed at the select board meeting on Feb. 25.

The board declined to send the plan to the Mass. Environmental Policy Act Office, however, where the draft would have been reviewed with a 20-day period for public comment. Instead, at the end of a long meeting with occasionally raised voices, vice chair Michael DeVasto, who chaired the meeting in John Wolf’s stead, suggested that a public hearing to discuss the plan was necessary before the state review.

Wolf, who attended the meeting remotely, told the Independent that he expects that public hearing to take place in the next couple of weeks.

“This is the largest municipal project that this town has ever engaged in and will ever engage in,” DeVasto said. “The select board has never deliberated about the targeted watershed management plan. I want to spend the time necessary.”

The presentation was preceded by years of discussion of the state’s new requirements for protecting watersheds from excess nitrogen, which can worsen water quality, increase harmful sediment and algal blooms, and damage eelgrass habitat.

Though fertilizers and runoff can contribute to excess nitrogen, the primary source on Cape Cod is nitrogen-rich human wastewater, which leaches from septic systems into the water table and then into ponds and embayments like Wellfleet Harbor.

The targeted watershed management plan, which was authored by consultants Scott Horsley and Anastasia Rudenko, has been in development since 2022 and includes input from the state’s Dept. of Environmental Protection. Failure to implement a management plan could lead to the imposition of much more stringent septic rules by state regulators.

The watershed management plan is “a 20-year plan with five-year check-ins,” Horsley told the Independent. At the end of each five-year phase, the town would meet with the DEP to discuss progress and changes in nitrogen data.

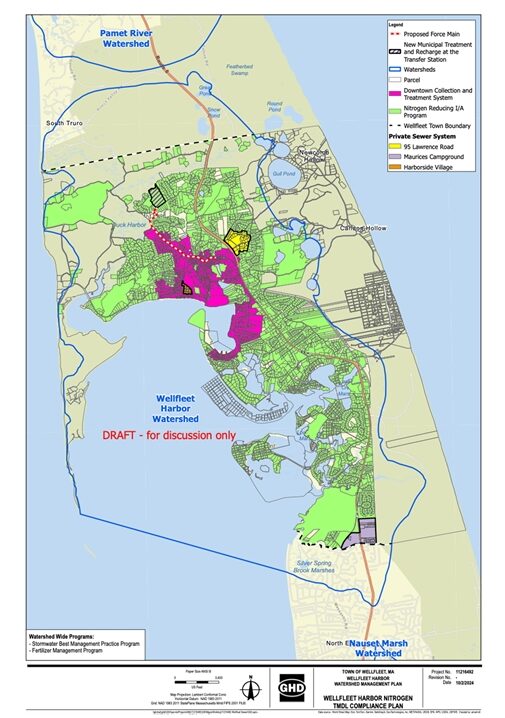

The “preferred” hybrid plan, called “Scenario A,” includes the downtown sewer system and the installation of enhanced Innovative/Alternative (I/A) septic systems in homes outside the sewer area, as well as smaller cluster systems for housing developments at Lawrence Hill and Maurice’s Campground.

A contingency plan, “Scenario B,” involves a larger sewer collection area and wastewater treatment plant. According to the plan, the estimated total cost of Scenario A is $210.2 million, while the contingency plan would cost at least $100 million more than that.

Nonetheless, board members DeVasto and Ryan Curley said that they disputed the plan’s preference for Scenario A, citing the cost of upgrading to enhanced I/A systems for such a large portion of Wellfleet’s housing stock.

“I propose that we accept the contingency district,” DeVasto said, adding that he preferred a larger sewer district and a smaller zone for enhanced I/A systems, which would be more in line with Scenario B.

Board member Sheila Lyons said that state funding for the town’s wastewater efforts could become less available with further delays.

“You need to get moving, and once you start, your story starts to unfold,” Lyons said, referring to a series of future opportunities to adjust the plan. “There’s really not a reason not to approve what’s here, knowing that this is subject to change.”

DeVasto, Curley, and Wolf said there was a need for more discussion on how the town could support homeowners who must pay for septic upgrades.

“The town is in a much better borrowing position than individuals,” Wolf said, and could negotiate more favorable terms.

The plan states that for an average single-family home, I/A septic upgrades are “slightly less than half the cost of connecting a home to centralized sewering and treatment.” The estimated cost of installing an I/A system is $53,924, the plan says, compared to an estimated $108,794 to connect to a downtown sewer.

Sewering does provide better nitrogen reduction, Horsley said, and can be attractive for other reasons: “It’s convenient, and maybe it increases the value of your home.”

DeVasto said he worried that the proposed sewer district could expand again in the future, which he said could lead to a double charge if some homeowners were to install an enhanced I/A system and then be required to pay again to connect to the sewer.

The sewer district in the management plan is the same one that was posted by the health dept. on Dec. 11 and published in the Independent on Jan. 16.

Board member Barbara Carboni said that a public hearing could be helpful, as the state’s public comment period would not support the kind of thorough public discussion that she believed was still needed in Wellfleet.

Some alternative strategies for nitrogen reduction, such as shellfishing and the Herring River restoration, were not included in the final draft, Horsley said, because the amount of nitrogen reduction that could be credited to those strategies was difficult to know without further monitoring. If their benefits were further established, the town could perhaps reduce the extent of future phases of sewering and I/A upgrades, Horsley said.

Although affordable housing projects are often controversial when it comes to wastewater, Horsley told the Independent, the cluster systems that are proposed for 95 Lawrence Road and Maurice’s Campground will actually improve water quality over the status quo in those areas.

“I do a ton of affordable housing work around the state,” Horsley said, including “on 40B projects, which tend to be controversial. The incredibly cool thing about 95 Lawrence and Maurice’s Campground is both of these projects are going to get the town a lot of affordable housing, and — I would capitalize, in underline and bold, the word ‘and’ — improve water quality.”