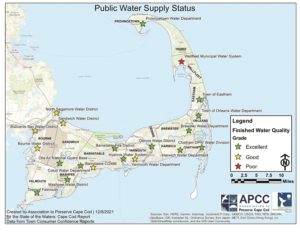

WELLFLEET — A report issued in late December by the Association to Preserve Cape Cod (APCC) singled out Wellfleet’s municipal water system as the only one among 20 on Cape Cod with “poor” water quality. But that conclusion is inaccurate and unfair, according to town officials, who said Wellfleet’s town water is “outstanding.”

The “poor” rating, published in what the nonprofit Dennis-based APCC calls its annual “State of the Waters” report, is flawed, according to Wellfleet Water Commissioner Jim Hood, because it is based on one incident of contamination found during routine testing and quickly remedied.

The rating, said Hood, “is not fair to us and the work we’ve been trying to do to improve the water supply here in Wellfleet.” None of the town’s water commissioners had heard of the report before being contacted by the Independent to comment on it.

The APCC report states that Wellfleet “received a grade of ‘Poor’ due to violations in 2020 of two drinking water standards, E. coli and total coliform bacteria, as well as several violations which required the town to issue a ‘boil water order’ to protect public health.”

The APCC’s drinking water rating, according to Executive Director Andrew Gottlieb, relies entirely on the annual consumer confidence report submitted by the town’s water supply company to the Mass. Dept. of Environmental Protection. He said the rating reflects the fact that a problem requiring remediation occurred. “That’s our definition of ‘poor,’ ” Gottlieb said. “We had no reason to expect Wellfleet’s rating. Nothing had been found in two prior years,” he added.

Nonetheless, Gottlieb said, “I believe the rating is fair.”

The APCC’s report was issued Dec. 22, according to Gottlieb, and a press release went out on Jan. 3. Asked why it took a year to issue the water system ratings, Gottlieb said that it takes his organization that much time to compile all the data it needs for its report, which extends beyond drinking water to include conclusions on pond and estuary health as well.

Hood objected to the reference to “several violations” in the APCC report, saying that multiple incidents did not occur.

“There was one event,” Hood said. That event was widely reported, including in the Oct. 1, 2020 issue of the Independent.

In September 2020, during routine flushing of lines, done to clear debris, the town’s water system operator, Whitewater Inc. of Charlton, found E. coli at the Coles Neck well field just north of town, Hood said. Measuring for coliform in drinking water is important because one specific form of the bacteria (E. coli O157:H7) can be dangerous, causing diarrhea, dysentery, and hepatitis, according to the CDC.

While the source of the problem was being investigated, the state issued an order to the occupants of the 290 homes served by the system, requiring tap water be boiled for at least one minute before drinking, washing dishes, or brushing teeth with it. Restaurants were required to boil water for five minutes.

A cracked wellhead cap found at the Coles Neck well field had allowed bacteria to get into the water there.

“Unfortunately, the town’s water supply company had not sealed off the water line,” said Hood and, as a result, bacteria traveled from the well field down to Coles Neck Road, he said. Tests indicated two properties near the top of that water line were affected.

The boil-water order was lifted four days after the bacteria were detected, after the water was treated with chlorine and subsequent samples reported to the state Dept. of Environmental Protection confirmed the system was clear, Hood said.

“The incident covered a weakness in the system that was addressed promptly,” said Water Commissioner Curt Felix. “The DEP was satisfied. The bottom line is Wellfleet’s water quality is outstanding.”

Whitewater Inc. General Manager Stephen Donovan would not respond to questions about the APCC’s report, saying that “the town of Wellfleet has asked we forgo responding until after the board of water commissioners has met and had an opportunity to discuss.”

The water commissioners planned to meet on Tuesday, Jan. 18 to discuss the report. Town Water Clerk Karen Plantier did not respond to multiple voicemail and email messages.

At their Oct. 5, 2021 meeting, the commissioners discussed positive tests for coliform bacteria in the municipal water system in September and again in October. Regular testing of the system’s water supply is required. When coliform bacteria are found, Felix said, the town follows DEP procedures, retesting the water for other contaminants.

“Coliform bacteria are ubiquitous,” said Felix. “It’s not dangerous. Everything in nature that’s consuming food and digesting it is producing these bacteria. Naturally, they’re more present in the soil.”

Hood referred to a 2017 nationwide tap water report by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group. Wellfleet was reported to have the lowest contaminant levels in Barnstable County, he said.

“That was the first time we ever had an event like that,” Hood said of the Coles Neck contamination. Even before the detection of E. coli there, the Coles Neck well field was not used regularly. “Right now, the Coles Neck Road well field is all sealed off,” Hood said.

The town mainly uses two wells at the Boy Scout Camp well field, near the Council on Aging on Old County Road. “That’s our primary water source and it has been since 2010,” Hood said. Two wells at the Coles Neck well field are at least 30 years old, with one redone in 2004 or 2005. “There are repairs that need to happen in conjunction with the installation of the new water main there.”

The town is installing a new $3.8-million water main at the Coles Neck Road well field that will enter town along Briar Lane, bringing the system’s secondary water source into compliance with DEP requirements for a redundant water supply. The town received a $2.5-million state grant for the project. Work is expected to start next week.

Hood said his largest takeaway from the 2020 incident had to do with the fact that, while most Cape Cod towns chlorinate their water routinely, Wellfleet does not. The contamination was an example of why it might have been a better decision to add chlorine to the town’s drinking water to kill parasites, bacteria, and viruses, he said.

“If it had been chlorinated, Whitewater would never have found this,” said Hood. “That decision was made well before my time,” he added. Hood has been a member of the board of water commissioners for 10 years.