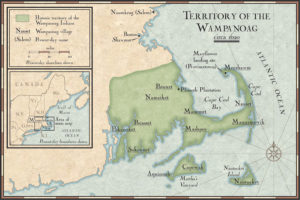

A federal judge ruled in favor of the Wampanoag Tribe of Mashpee on June 5 in a suit the tribe filed against the Dept. of the Interior, which had attempted to take the tribe’s land out of trust in late March this year.

In his opinion, D.C. District Court Judge Paul Friedman wrote that the Secretary of the Interior’s decision was “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, and contrary to law.” He remanded the Dept. of Interior to reconsider its decision by applying a legal test “correctly this time.”

The Dept. of Interior’s strategy was to argue that the Wampanoags must prove they were under federal jurisdiction in 1934 to have land held in trust by the federal government.

The tribe had presented various forms of evidence documenting that the Wampanoags were under federal jurisdiction before 1934. But Interior dismissed that evidence.

In his ruling, Friedman wrote that the tribe’s evidence does indeed prove it was under federal jurisdiction. Wampanoag students attended the Carlisle School, a boarding school for Native American children, for decades. The judge ruled that this fact, along with census reports from the early 1900s and other reports conducted by the federal government, were proof of the tribe’s status.

In a June 5 online statement, Mashpee Wampanoag Chair Cedric Cromwell wrote that maintaining tribal land is vital to protecting tribal sovereignty, culture, and traditions, and celebrated Friedman’s ruling.

Cromwell warned, however, that the “work is not done. The Dept. of Interior must now draft a positive decision for our land as instructed by Judge Friedman. We will continue to work with the Dept. of the Interior — and fight them if necessary — to ensure our land remains in trust.”

Observers of the current president’s moves on this issue believe this attempt at disestablishment was motivated by casino interests. As the Independent reported on May 28, the Trump administration has close ties to casinos in neighboring Rhode Island, which expect to face competition from a casino on the Wampanoags’ Taunton land.

David Silverman, a professor of colonial and native history at George Washington University, said, “I don’t think you can separate this from the fact that Elizabeth Warren is a champion of Mashpee,” Silverman said. “Personal vendettas and financial interests are now the drivers of federal policy.”

In order to prevent future challenges of this kind to tribal sovereignty, Congress would need to pass legislation that fixes the complex legal definition of “Indian.”

Two such bills are currently stalled in the Senate. The first, introduced by Rep. Bill Keating, would clarify the Wampanoag reservation’s status and prevent future legal challenges. The second would more broadly reaffirm tribal sovereignty across the U.S. and strike the 1934 requirement.