PROVINCETOWN — Olga Shpak is as surprised as anyone that she became a war volunteer.

Growing up in Soviet Ukraine, Shpak had a hard time collaborating with other kids. She swore she would never get a job that forced her to work with people. Her teachers blamed her parents, accusing them of raising an individualistic child. “In the Soviet Union, that was the worst thing ever,” she said.

Shpak had no trouble relating to biology, however, and was keen on working with marine mammals, especially whales. She left Ukraine as a young adult and moved to Moscow for graduate school to pursue that passion.

For 25 years, she devoted herself to studying and protecting marine mammals around Russia, particularly in the Sea of Okhotsk in the far east. She became an authority on the country’s marine mammals and was a researcher at the prestigious A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, part of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

But when Russian forces on the Ukrainian border near her hometown of Kharkiv seemed poised for invasion in February 2022, she packed a small backpack and went home, leaving her life as a marine biologist behind. She now serves in a network of volunteers who are integral to Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s invasion.

The war has been “a series of discoveries of what I was capable of,” Shpak told a crowd of scientists and Provincetown locals at the Commons on Feb. 3. She was doing a series of talks and meetings across the U.S. to drum up support for the organization she now directs, Assist Ukraine.

This was not Shpak’s first time in Provincetown. She worked as an aerial observer for the Center for Coastal Studies Right Whale Ecology Program in the winter of 2015. Returning after two years on the front lines felt like a “switch from one planet to another,” she said. “I don’t know how I’ll talk about war among these beautiful paintings,” she said, gesturing to the art on the walls.

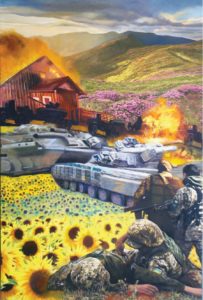

On Feb. 23, 2022, Shpak joined her mother, her brother, and his children in Kharkiv. That night, they awoke to the sound of bombs. The invasion had begun.

According to Shpak, no one in Kharkiv was surprised by the invasion. People had been making plans and preparing go-bags for months. But there is only so much preparation one can do, she said. She likened the invasion to preparing for a flood: no matter what you do, no one is ready to wake up in knee-deep water.

If those bombs were the rumblings of thunder, the tanks that rolled into Kharkiv a few hours later were the deluge.

As Ukrainian forces arrived in the city to head off the Russians, Shpak’s brother and his children fled. But her 84-year-old mother refused to leave, and Shpak decided to stay, too. It wasn’t long before she headed to the aid station in Svobody Square, the city’s main square, to start giving supplies to troops. “I didn’t have much of a choice,” she said.

That February’s incursion was the beginning of a six-month occupation of the Kharkiv region by Russian troops, which mostly ended in September 2022, though bombing continues.

The situation in the city was often dire. Shpak described one day when the Russian line came within a few blocks of Svobody Square, and a woman she was working with told her, “If Russians pass through those blocks, we’re doomed.” She told Shpak that if the volunteers were captured, “we’ll pray for a quick death.”

Shpak said she didn’t believe the woman at first. But in August, Ukrainian soldiers pushed Russian forces out of Kharkiv and began searching areas that had been occupied. They found mass graves and basements where soldiers had been tortured.

“War makes everything around you black and white,” Shpak said. “You either help one side or you let it die.”

Shpak first got involved with Assist Ukraine when Art Davidson, an author and activist from Colorado who cofounded the charity, contacted Shpak and sent her money. She remembers him telling her, “Don’t ask me if you can spend money on this or that.” That would be up to the people on the ground.

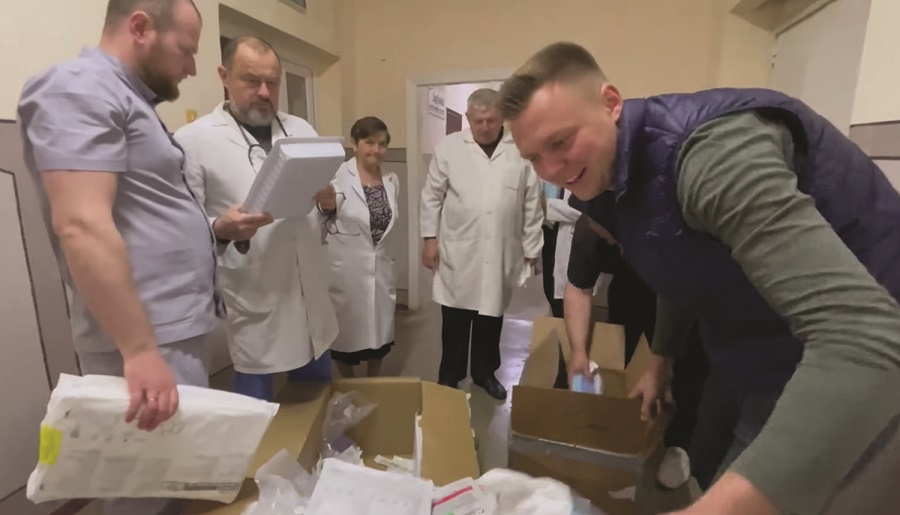

Medicine, tourniquets, generators, and thermal drones all played their part in keeping Ukrainians alive. Shpak reached out to her former marine mammal biologist colleagues, including at the Center for Coastal Studies, to see if anyone could donate old binoculars or radios. She got loads of supplies back. She said the soldiers loved learning that their binoculars came from whale biologists.

Shpak’s role at the organization has grown. She began handling the procurement of valuable supplies and driving truckloads of gear across the country to the troops at the front lines. These trips, she said, are dangerous, but she always has “a line of people who want to go with me.”

Volunteering has given Shpak a new set of skills. She said she learned to read prospective volunteers’ faces in seconds to assess their trustworthiness. Since volunteers will have access to details about troop locations and plans and to each other’s personal information, “You put your life in fellow volunteers’ hands,” she said.

The war also enables volunteers to do things they never would have tried to do before, Shpak said. “We can eat less, sleep less, do more, carry more stuff,” she said. “You learn things you didn’t know existed in you.”

In spite of these optimistic words, Shpak also said the experience of war has left her and the rest of the volunteers traumatized. “For two years, no one in Kharkiv went to bed without thinking they might not wake up,” she said.

The city is so close to the Russian border that air raid sirens usually went off after the bombs had already hit. “Every time you pass a ruined building, you think, ‘I could have been in there.’ Everyone is traumatized now,” she said. Ukraine is a “PTSD country.”

Shpak has found that the best way to survive is helping however you can. “My prescription is work, work, work,” she said. “The more you do, the less you have time to think and contemplate.”

But helping in this way is also incredibly rewarding, Shpak said. “The emotions you get when you help people,” she said, “is something that is never enough.”