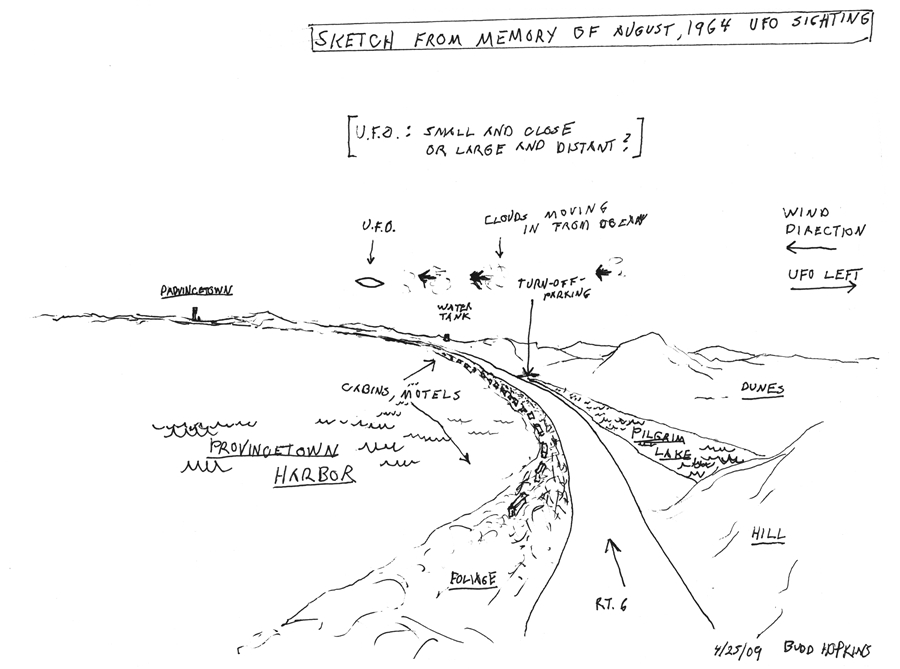

If you’ve driven down Route 6 from Truro to Provincetown, you’ve experienced that breathtaking moment when Cape Cod Bay emerges all at once and the dunes raise their sandy heads along East Harbor. At that exact spot on an August day in 1964, the soon-to-be father of the alien abduction movement saw his first UFO.

Budd Hopkins was on his way to a cocktail party at art collector Hudson Walker’s home in Provincetown. Hopkins (1931-2011) was a successful Abstract Expressionist painter whose circle of friends and mentors back in New York included Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, and Willem de Kooning.

In the car with Hopkins was his first wife, Joan Rich, and their houseguest Ted Rothon. As Hopkins wrote in his 2009 memoir, Art, Life and UFOs, the three had been having an animated conversation when were they shocked into silence. They had seen a “small, lens-shaped object in the sky” that “appeared to be circular and utterly without details — no lights, wings, doors, windows, or protuberances of any kind.” It flew directly against the wind at the speed of a small airplane before disappearing behind a cloud bank, he wrote.

When they arrived at the party, Hopkins told some of the artists there what he had seen on the drive into town. According to Hopkins, several others at the party — including painter Giorgio Cavallon, photographer Molly Cook, and poet Mary Oliver — said that they had seen similar things around the Cape. Hopkins recorded the questions he asked himself that evening: “What is going on? Were these experiences actually widespread, an underground phenomenon that no one discussed, even though they might be of potentially great importance?”

Hopkins began to study stories of unidentified flying objects and gradually became persuaded that “these craft-like objects, which behaved as if they were under intelligent control, could be extraterrestrial in nature.” But it wasn’t until November 1975 that Hopkins’s extraterrestrial career began in earnest.

George O’Barski, proprietor of a liquor store near Hopkins’s home in New York City, approached him with a story of an alien landing he had witnessed in North Hudson Park, N.J. O’Barski’s story led Hopkins to conduct an investigation that became an article published in the Village Voice in 1976. (It was later reprinted in Cosmopolitan.)

According to Eddie Bullard, an expert in the field of ufology and author of UFO Abductions: The Measure of a Mystery, after Hopkins published the article he became a go-to person for others who were haunted by memories of alien visitation. Bullard describes how these people often had a sense of missing time when recounting these experiences, leading Hopkins to “team up with a psychologist to hypnotize these haunted individuals.” Hopkins later did the hypnosis on subjects himself. The process led many people — or “victims,” as Hopkins referred to them — to unearth supposedly hidden memories of alien abduction.

Hopkins claimed there was a plethora of evidence for the validity of these abduction stories, including recurring physical marks on people’s bodies; ground traces at UFO landing sites; and the recurrence of certain motifs across stories. The experiences described under hypnosis by the purported alien abductees generally involved aliens probing their naked bodies and removing cells, sperm, or eggs. Hopkins speculated that these extraterrestrial visitors could be conducting a eugenics program through crossbreeding with humans. In 1989, Hopkins founded the Intruders Foundation to support victims of abductions and raise an alarm about the phenomenon.

His findings led to a series of books on the subject, including Missing Time (1981) and the New York Times best-seller Intruders: The Incredible Visitations at Copley Woods (1987). Intruders told the story of Kathie Davis, an Indianapolis woman who claimed to have experienced serial abductions and borne a hybrid alien-human child.

According to Bullard, Hopkins’s writings spurred greater interest in alien abductions in the 1980s and ’90s and helped attract scholars — such as Harvard psychiatrist John Mack — to the field. The movement reached its peak in 1992, when a miniseries based on Intruders debuted on CBS and an abduction study conference was held at M.I.T.

But Bullard says that interest in alien abductions gradually began to wane, mainly due to evidence that repressed memory therapy through hypnosis can create false memories. Most of the supposed physical evidence of abductions has since been scientifically dismissed as well. It’s likely the stories Hopkins gathered were similar because he asked “leading questions,” says Bullard, and “subjects willing to believe played along.”

While the Outer Cape is best remembered in UFO lore as the place where Hopkins’s interest in the subject was first piqued, for Hopkins it was also a second home and a place of community that supported his art throughout his life. Hopkins first came to Provincetown from New York in June 1956 after being hired by Nat Halper as an attendant at his HCE Gallery at 461 Commercial St. He met Joan Rich on the ferry back to Boston that summer, as well as several influential artists. Hopkins writes in his memoir that he “returned to the Cape virtually every summer” following that first visit, building a studio in Truro and then a house in Wellfleet. (Both were designed by architect Charlie Zehnder.) In 1977, he became one of the 12 founders of Provincetown’s Long Point Gallery, a celebrated cooperative artist-run gallery that operated for more than 20 seasons.

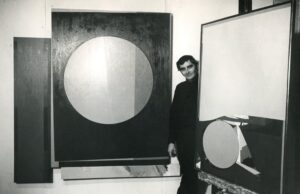

His daughter, Grace Hopkins, an artist herself and director of the Berta Walker Gallery in Provincetown, lives in the Wellfleet house that Hopkins built. She says it is her father’s art, more than his association with ufology, that interests her. His paintings, which are in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art among other institutions, were often characterized by shapes overlaid with interlocking flat sheets of color. Circles were a recurring motif, as in Black Sun, which depicts a black circle within an interlacing mesh of multicolored rectangles.

Grace Hopkins says that, despite claims to the contrary, the circles in her father’s paintings do not represent UFOs. In his memoir, Budd Hopkins writes that the shape represented both an entranceway and a dead end, simultaneously invoking “an imperious, controlling solid and a mysterious void.” Although there may not have been an intentional link between the circles in the paintings and the 1964 UFO sighting, Hopkins writes in his autobiography that he was “susceptible as anyone” to unconscious influences.

Grace does admit that her father’s later work — in particular, his “Guardians” series, large geometrical sculpture-paintings — is connected to UFOs to some degree. “He saw [the paintings] as protectors of the people,” she says, adding that he made her a small three-dimensional guardian and taped it to her car dashboard to keep her from having an accident.

Whatever extraterrestrial influence may or may not have affected his work, Hopkins was truly his own artist. The simple colors and sharp lines of his paintings invoke primordial feelings of strength, surrender, and wonder.

Whether it involved a UFO over Route 6 or a canvas in his studio, Hopkins was always sure of the truth of his work. Hopkins writes in his memoir that he spent much of his adult life answering the same question posed by UFO skeptics: “Is there really something to it?” It’s a question he heard in his life as an artist as well.

“In a way, this basic question about the UFO phenomenon is a bit like the hoary old chestnut, ‘What is Abstract Art all about?’ ” he wrote. “Or, more personally, ‘What do your paintings mean?’ Try answering any of this in 25 words or less.”

Berta Walker, who knew Budd Hopkins and now represents his work in her gallery, says that he was utterly original. “He has a genuine, long-lasting place in the history of American art,” says Walker.

Wellfleet artist Bob Henry agrees, saying that his old friend “ventured into color combinations” that were way ahead of his time. While Hopkins’s interest in alien abductions eventually distracted him from his painting career, Henry says that Hopkins was always regarded as a cherished member of the art community, both on the Cape and in New York.

“We don’t reject people because of what they are,” says Henry. “We’re a bunch of misfits anyway.”