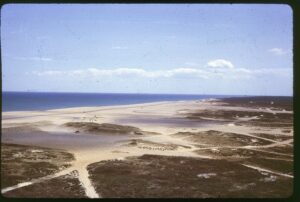

WELLFLEET — Above Marconi Beach, passersby may come across a strange concrete object nudged into the umber dunes, entirely out of place against its pristine natural backdrop.

Every morning at dawn, Wellfleet resident Paul Savage had walked by it — a large cinder block with a corroded metal ring in its center gathering sand and seaweed.

“I’d been looking at it for years, and I never really knew what it was,” Savage says. One morning after a windstorm, Savage saw that the bluff had eroded, and the object had slipped down to the edge of the beach. He took a picture of it to illustrate the effects of erosion. What he received in response was a history lesson.

Retired Wellfleet police officer Marc Spigel told Savage the mysterious object looked like a gun turret base, the kind that dotted the lip of the dunes between Marconi Beach and Marconi Station more than 60 years ago.

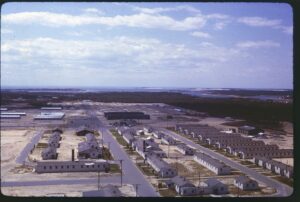

It is a vestige of the Outer Cape’s not-so-distant military past, when 1,738 acres on the shore were used as a U.S. military training ground known as Camp Wellfleet. In its heyday, up to 1,000 Army reservists dropped flour bombs and shot down remote-controlled airplanes over the Atlantic Ocean here.

Now overgrown with beach heather and pitch pine, the area is designated by the federal government as a Formerly Used Defense Site (FUDS). On occasion, a new round of cleanup conducted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers brings its history to light again.

Last month, the town received word from the Corps that the land was due for another sweep.

The 300-Mile Shooting Range

The U.S. government filed a “petition for condemnation” in the Barnstable County Registry of Deeds “for public uses of 1,800 acres of land, more or less, situated in the Town of Wellfleet” on July 26, 1943.

Germany had invaded Poland less than four years earlier, and the U.S. was at war. The Mass. Military Reservation in Falmouth, home to the state’s National Guard, came under the command of the U.S. Army and was named Camp Edwards. Auxiliary sites popped up in Sandwich and South Wellfleet, and by 1943 the Army decided it needed more land.

The federal government’s petition for condemnation of the land in Wellfleet, according to Registry records, was extendable for yearly periods “during the existing national emergency.” There were 32 landowners listed on the deed.

“It was wartime; if the Army knocked on your door and told you they needed your land, you gave it to them,” says Pam Tice, who lived on Old Wharf Road during Camp Wellfleet’s acme and who has written about the camp on her South Wellfleet history blog.

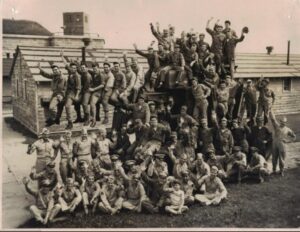

Camp Wellfleet was mainly used as an anti-aircraft center. In 1945, it was briefly turned over to the U.S. Navy as an adjunct of the Hyannis Naval Auxiliary Air Facility and used as a bomb target site. Then it was returned to the Army’s 548th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion to be used as a firing range.

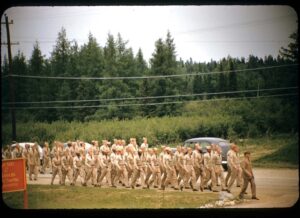

For those who lived on the Cape at the time, the sound of ballistics and military marching was as quotidian as the salt air.

“When I was a kid, you could hear the guns booming in the background all day,” Tice says. “And at night, if the wind was blowing in the right direction, you would hear them playing taps, and you would wake up to reveille.”

For children and adults alike, the legions of young men clad in fatigues — or out of them —was a sight to behold. “Every once in a while, a bus would pull up, and the soldiers were all taken to the beach for a swim,” Tice says. “They would make a big stir.”

But coexistence among Army men and locals wasn’t always copacetic. In 1951, an announcement that the Army planned to expand its firing range to 300 miles along the back shore from Race Point to Chatham shook up townspeople and dominated the news.

According to Cape Codder articles from that time, the Corps of Engineers put notices of the plan in post offices across the Outer Cape, stating that it would turn the back shore into an exclusive “gunnery range for anti-aircraft firing practice and for air-to-ground phases of aerial gunnery on a day and/or night continuous basis.”

There were no public hearings scheduled, and objections were to be filed in triplicate in Boston by Sept. 4, less than two weeks after the initial announcement on Aug. 23, 1951.

On the Cape Codder’s front page that week, a headline “warning to Outer Cape” in all capital letters stated that the plan “threatens the whole structure of life on the Outer Cape. Fishing, recreation, and real estate business is gravely threatened by the plan.”

Town meeting resolutions, petitions, and public letters poured forth. In an Aug. 30 article, the Cape Codder reported that Orleans, Chatham, and Eastham discussed the issue at special town meetings, “with a handful of non-resident taxpayers allowed to take part in the voting.”

The federal government heard Cape Codders loud and clear: the Army Corps held a hearing on Sept. 27 at Wellfleet’s Legion Hall on Commercial Street. According to the Cape Codder’s report, the hearing drew 500 people and lasted for “five lunch-less, smoke-less hours.”

As is Wellfleet tradition, local fishermen and politicians “minced no words and showed no feeling of being impressed by braided uniforms.”

The Army eventually surrendered, sort of. In December 1951, it announced concessions “that would offer the least interference to all parties concerned,” the Cape Codder reported, including direct telephonic communication between fishing boats and range officers at Camp Wellfleet, firing schedules posted weekly, and sunken targets recovered so as not to interfere with navigation.

The Army’s 548th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion used the firing range until 1956, when the base was abandoned; the land was conveyed to the National Seashore in 1961.

Cleaning the Scraps

Former Town Administrator Rich Waldo wrote to the select board on Jan. 2 that he received correspondence from the Army Corps of Engineers detailing its plans to “minimize exposure to explosive hazards” at the former Camp Wellfleet site. It appeared that traces of the outpost remained.

Because Camp Wellfleet is one of more than 10,000 formerly used defense sites across the country, hazard mitigation at the site falls under the purview of the Army Corps.

Since the 1990s, the Army Corps has conducted three rounds of cleanups, according to David Crary Jr., the retired fire management officer for the Seashore who served as the Park’s liaison for those projects. Surveys of the land via magnetometer-equipped helicopters in 1999 detected 80 sites with possible unexploded ordnance, Crary says. In the first two cleanups, the Army Corps recovered over 3,541 pounds of munition debris and 5,109 pounds of scrap metal, according to an Army Corps document. Those items included smoke grenades, bazooka rounds, dove missiles, and an inert 250-pound bomb.

According to an Army Corps press release from 2003, groundwater sampling in 2000 did not identify any contaminants above action levels in seven monitoring wells.

This time, says Army Corps spokesman Bryan Purtell, the planned cleanup is limited to “land use controls,” like sign postings to guide site inspectors, Park personnel, and passersby to report any old military equipage they might come across. This will likely be the last of the remedial work to be done on the Camp Wellfleet FUDS, according to the project plan.

Still, every so often local agencies get calls alerting them to strange metal objects poking up from the sand, says Wellfleet Police Chief Kevin LaRocco.

In 2008, the National Seashore found fuse containers protruding from the dune, and in 2009, about 30 .50-caliber rounds were found, according to an Army Corps document. In 2014, the state police bomb squad, the agency tasked with recovering ordnance, evacuated Marconi Beach after a fisherman found a 14-inch projectile washed ashore. The state police detonated it onsite.

The Independent previously reported on the discovery of nine World War I-era bombs in a Wellfleet man’s back yard in 2020, which the U.S. Navy and state police bomb squad detonated in the town’s sand pit.

“Someone dropped a mortar off in my office years ago,” Crary says, an addition to the list of recovered ordnance. But he adds that in the 60 years since Camp Wellfleet was turned over to the Seashore, there have not been any injuries from unexploded ordnance.

“We can never say for sure that our site is free of munitions,” Army Corps project manager Gina Kaso wrote to the Independent. “We want to educate people to make sure that they know what to do if they encounter something that might be a munition.”

Kaso reminded the Independent of an important dictum for finding traces of the old Camp Wellfleet:

“Recognize, Retreat, Report!”