If town records offer little detail about the “fearful and fatal sickness” on Cape Cod during the late winter and early spring of 1816, the cemeteries are a melancholy testament to the toll it took. No town was harder hit than Eastham, and no graveyard bears more headstones from that year than Bridge Road Cemetery, once known as the Herring Pond burial ground, site of the town’s Third Congregational Church (1720-1830).

By early February 1816, newspapers were reporting on the great mortality, several saying that it was “vulgarly called the bastard pleurisy.”

The epidemic in Wellfleet was said to be confined to a small neighborhood, but by April, 40 were reported sick in Truro. In Truro — Cape Cod (1883), Shebnah Rich wrote that church records had named the illness malignant fever, putrid fever, spotted fever, or cold plague, and that 36 had died, the first on March 9 and the last on May 23.

Writing about Eastham in his History of Cape Cod (1869), Frederick Freeman noted that in 1816 the town “was scourged by unusual sickness, the origin of which has never been satisfactorily ascertained. That a township proverbially healthy should, in the short space of about four months, finds its population more than decimated, was an occurrence fraught with much alarm.” By the time the mysterious disease had run its course, 72 had died in Eastham, more than 10 percent of the population. Dozens more who had fallen ill recovered.

The 1844 history of Eastham, Wellfleet, and Orleans by the Rev. Enoch Pratt provides a hint. “The most successful prescriptions that were made,” he wrote, “were powerful emetics and cathartics.” He may have been referring to a botanical healer named Samuel Thomson.

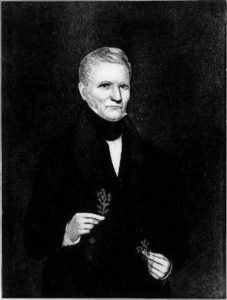

Born in Alstead, N.H., in 1769, Thomson had little formal education and had come by his knowledge of plant remedies by observation and experience. His earliest “treatments,” using herbs, roots, and barks, were conducted on family members, neighbors, and himself, and their success furthered his belief that conventional doctors were poisoning and killing their patients with minerals such as mercury and calomel (mercury chloride) and procedures such as bloodletting.

By 1806 Thomson had developed the Thomsonian System of herbal remedies, to which anyone could purchase the “rights” for $20, thereby becoming their own doctor. Thomson attacked the established medical community and their “caustics.” In turn, university-trained physicians called Thomson a charlatan.

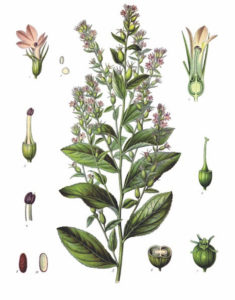

Central to Thomson’s system was the belief that cold was the culprit and that disorders arose from restricted perspiration. Thus, it was vital that the body’s natural heat — the fountain of life — be restored to promote perspiration and evacuate toxins. This was accomplished first with an emetic herb to induce vomiting. Thomson’s plant of choice was Lobelia inflata, also known as Indian tobacco or puke weed, followed by Capsicum, the pepper, to restore internal heat. Additional preparations that rekindled heat by restoring digestion and appetite, as well as external steaming were administered as needed. In 1813, Thomson obtained a patent for a remedy he called “Fever Medicine.”

Thomson first visited Eastham in 1815 to collect marsh rosemary (sea lavender) for use in a preparation. The following spring he returned to gather more plants, only to find that dozens had died from the “spotted fever” or the “cold plague.” Desperate for a cure, the people of Eastham asked to try Thomson’s medicine.

After tending to a handful of cases and leaving medicine with those who had purchased the rights, Thomson returned to Boston only to be called back a week later. During a two-week stay, he treated 34 patients, only one of whom died, whereas 11 of the 12 who were tended by local doctors had died.

In narrating his Eastham experience, Thomson made special note of the need to change the clothes and bedclothes “to guard against taking back any part of what has been thrown off by the operation of the medicine.” Thomson’s story was supported by several distinguished members of the community, including two selectmen and the Rev. Philander Shaw, Congregational minister at Eastham from 1795 to 1838.

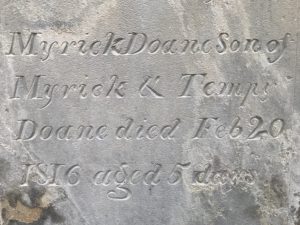

Shaw knew personally the fever’s devastation, having lost two sons, nine-year-old Oakes and three-year-old Joseph, in February. The family of Myrick and Temperance “Tempy” Doane suffered unthinkable loss. Tempy died on Feb. 18 at age 32, three days after giving birth. Over the next three days, four of the Doane children — Clement, William, Maria, and newborn — succumbed.

What caused the pestilence that descended over the Lower Cape, touching virtually every family in Eastham? Shebnah Rich, writing about the “strange epidemic for which physicians could give no satisfactory reason,” noted that it did not seem to be contagious. Its symptoms were chills and pains in the head, chest, side, arms, and legs, and its victims experienced great distress and debility.

Truro church records called the disease by names related to the Greek word typhos, meaning smoke or haze, and applied by Hippocrates to illnesses characterized by mental stupor caused by fever. With a long and deadly history, typhus was originally believed to be caused by a virus. Not until the early 20th century was its cause, the Rickettsia bacteria, isolated.

Rickettsia infections, spread by ticks, lice, mites, and fleas, are divided into two groups, spotted fever and typhus fever. The louse-borne bacteria R. prowazekii is responsible for epidemic typhus, not contagious but spread by infected body lice moving from person to person. Symptoms of epidemic typhus include body aches, fever, chills, stupor, and a spotted rash. Outbreaks in the 18th century occurred during the colder months when people were confined indoors, unable to bathe or wash clothes and bedding. It seems likely that what occurred at Eastham was, indeed, an outbreak of typhus, terrifying then but now uncommon and treatable with antibiotics.

In what seems to be too remarkable a coincidence to overlook, here we are today navigating a pandemic, trying to assuage fear of the unknown while sorting through many of the same questions: What caused the pestilence? What treatment might work? Did the people of Eastham worry about a second wave the following year?

As with the Rickettsia bacteria, a treatment for the virus will be discovered and what was once terrifying will become less so, though the world we knew just a few months ago has been changed.