If you haven’t heard the term passive house, Bob Higgins-Steele would like a word with you. As a member of the Truro Climate Action Committee, he is trying to spread awareness about this climate-conscious building philosophy.

Its goal is simple, says Higgins-Steele: build a home that is practically airtight and thus drastically more efficient to heat and cool than a traditional house. Given that most of a building’s energy consumption goes towards controlling its temperature (55 percent, according to the U.S. Dept. of Energy), passive homes have huge emissions-slashing potential — and therefore value in the battle against the climate crisis.

Finding one of these houses on the Outer Cape, however, is not easy. Passive House Massachusetts is a membership organization that promotes the approach, but its directory lists only two such homes on all of Cape Cod, both in Falmouth.

Jay Gainsboro, 68, a high-tech and consumer products entrepreneur, says he asked Wellfleet builder Robert Bacon to incorporate passive principles in his house, which went up near Mayo Beach in 2014. What Gainsboro was looking for was a house that would use virtually no power from the grid. The house is actually “net positive,” meaning it produces more electricity from its solar panels than it uses, even with an electric car drawing power from the system.

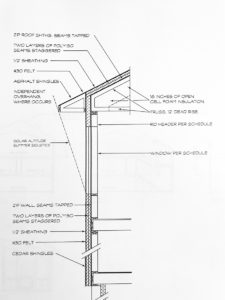

A tight building envelope is the main reason his house is so energy efficient. Windows are triple-paned. The doors, made by Schüco, lock onto their frames from the top, bottom, and side. With virtually no pathways for air to leak in or out, passive houses maintain temperatures exceedingly well. Gainsboro shows off the fact that the whole 2,000-plus-square-foot house is heated and cooled with three wall-mounted mini splits.

There’s also a heat recovery ventilation system in the basement to bring in fresh air. The home’s seal is so tight you could theoretically use up all of the oxygen inside, the owner notes.

Why aren’t there more passive houses around here? One issue is cost. According to the Passive House Institute, a nonprofit that trains and certifies builders, passive houses cost around 5 to 10 percent more to build than conventional houses. Up-front costs stand to rise anyway, though, as the state’s recent climate law, passed in March, will push the building “stretch codes” all four Outer Cape towns have adopted in the direction of net zero.

The other problem, Bacon says, is that while the approach makes sense with new construction, bringing an existing house up to passive standards “is nearly impossible.” While he’s done retrofits, he says the investment required for such an intensive project is out of the price range of most renovators.

So where does this leave most of us?

Higgins-Steele says there’s nothing wrong with adopting an incremental approach to supporting passive heating and cooling.

Energy efficiency at Gainsboro’s house is certainly aided by design. One time-tested example: a wall of large triple-paned windows faces due south, the optimal direction for maximizing sun exposure. In the summer, an overhang above the windows blocks the rays from entering the room, keeping it cool. In the winter, when the sun sits lower in the sky, sunlight pours in, bringing the room up to 80 degrees just by virtue of solar gain.

Higgins-Steele suggests making a long-term plan for your house. “Ask yourself, ‘What do I do when my water heater breaks down?’ ” he says. Then take inspiration from Gainsboro’s mini splits. Or his heat-pump hot-water heater — it’s two or three times more efficient than the conventional electric kind.

Maybe you won’t achieve airtight perfection. But, Higgins-Steele says, “You won’t miss big chances to do something meaningful for yourself and the climate.”