PROVINCETOWN — Almost 160 people, including many of Provincetown’s nightclub owners, bar managers, and hotel and restaurant staff, came to town hall on June 3 for an unusual kind of civic meeting: an “Active Shooter Attack Prevention and Preparedness” training session given by FBI agents from offices in New York City, Boston, and Lakeville.

The session was organized in the wake of a May 10 alert from the FBI and Dept. of Homeland Security on a “heightened threat environment” from “foreign terrorist organizations and their supporters” against LGBTQ gatherings and venues, especially during Pride celebrations in June.

That warning was not specific to Provincetown, the agents said. It cited a recent increase in anti-gay recruitment language from the terrorist organization ISIS; the eighth anniversary of the mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla. in June 2016; and the arrest of three ISIS sympathizers who had planned to attack a Pride parade in Vienna, Austria, last summer.

Assistant Town Manager Dan Riviello told the Independent he has periodically heard from business owners worried about safety since arriving in town in September 2022, so after the May 10 warning he reached out to friends in the FBI to see if they could arrange a training session.

“I knew the FBI was doing walkthroughs and training for gay venues in New York City,” said Riviello.

Special Agent Anthony Grecco Jr., who is gay, came from the FBI’s New York field office to deliver the attack prevention training. He also walked through 10 Provincetown venues on June 3 and 4 to help them assess their safety plans, he said.

“We talked about their security plans, their exits, their medical response plans,” Grecco said. “We don’t tell people what to do, but we do have a conversation about best practices.”

Run, Hide, Fight

The town hall session focused on a “Run, Hide, Fight” paradigm that Grecco said has largely replaced earlier guidance that focused on “locking down” a room and remaining silent.

“There is no single best course of action — everything is dependent on your situation,” Grecco said. “If you have escape routes and you have mobility, you probably want to take those escape routes, even if that is through a window or over a fence.

“Some of the staff here in Provincetown have pointed out to me that they have exits behind the bar that you might not know about,” Grecco said. “Make sure you’re looking for every possible option of getting out.”

If you’ve hidden in a room with a closed door, barricading it with thick objects and silencing phones is important, Grecco said.

Grecco said that “lockdown” strategies had led to some bad outcomes.

“If you’re treating it like the old nuclear bomb drills, ‘Everybody under a desk,’ you can reach some worst-case scenarios if the attacker is already inside or can shoot out the locked door,” he said. “People are stationary and helpless; they don’t have a plan, and each shot from that firearm can potentially create another victim.

“Fighting is only a last resort — but if it comes to that, look for improvised weapons like broken bottles or fire extinguishers and try to coordinate with two or three other people and make a plan,” Grecco said. “You’re trying to get the shooter’s arms to their sides, get them on the ground, and get on top of them and fight for your life.”

Another group of slides titled, “Debunking the Firearms Myth,” proposed ways a potential victim might overcome a shooter and be able to jam an assault weapon or stop the hammer of a gun from hitting the firing pin. A slide showing an AR-15-style rifle pointed out that a shooter would have to reload after 20 or 30 shots and suggested where one might grab an assailant’s assault rifle: not by the muzzle, because it will be hot.

A question came from the second row: “Is it ever a good idea to play dead?”

Grecco said he couldn’t rule that out entirely — but that at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando the shooter had time to “revisit” his victims and kill survivors. “Playing dead might be your only option, but you should constantly be looking for an opportunity to escape,” Grecco said.

A fourth priority, Grecco said, was to immediately address major bleeding in people you might be sheltered with.

“The number one cause of preventable death in active shooter situations is blood loss from the arms and legs, which can actually be addressed by people nearby,” he said. “There used to be a lot of apprehension about tourniquets, but we strongly recommend having them on hand because they can significantly increase the likelihood that someone will survive a gun or knife wound.”

FBI agents passed around about 20 combat-grade tourniquets for audience members to handle.

“You want to place the tourniquet high on the limb and very tight,” Grecco said, as people experimented with the devices on their neighbors.

Reporting Hate Crimes

After the audience was done trying on tourniquets, special agent Matt Ott from the FBI’s Lakeville office spoke about federal hate crime laws and the definition of illegal threats.

“A hate crime is a crime where the motivation for committing the crime is based on bias against a protected class,” said Ott. “To prosecute as a hate crime, we are looking for a specific articulated threat to commit unlawful violence.

“Political hyperbole, like ‘I’m going to shoot everyone who votes for so-and-so,’ wouldn’t count,” Ott said, “but once it’s specific, and it’s physical harm, that’s where you can get to federal hate crime charges.”

The federally protected classes are race, color, national origin, religion, disability, sexual orientation, familial status, sex, gender, and gender identity, Ott said.

All threats to harm someone can be criminal, Ott said, but threats to harm someone based on their identity in a protected class can be prosecuted under federal law in addition to state law. He invited the audience to send tips to the FBI’s anonymous online form, tips.fbi.gov.

Many in the audience asked questions specific to their workplaces. Grecco said he couldn’t answer every hypothetical, but the overarching idea was to keep moving and making new plans.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on June 6, incorrectly identified an FBI agent’s first name. It is Anthony Grecco Jr., not “Michael.”

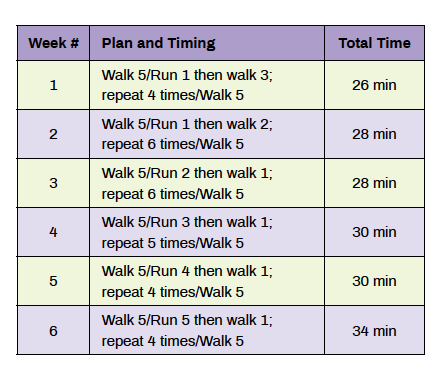

If you find the workouts too easy, you can progress more quickly. If they’re too difficult, go back a week or repeat a week until it feels manageable. Listen to your body; you’re looking for moderate exertion, say seven or eight on a 10-point scale, not an all-out effort.

If you find the workouts too easy, you can progress more quickly. If they’re too difficult, go back a week or repeat a week until it feels manageable. Listen to your body; you’re looking for moderate exertion, say seven or eight on a 10-point scale, not an all-out effort.