Longtime Truro resident Elizabeth Bradfield travels in far-reaching yet compatible directions. She’s a published poet, photographer, environmentalist, and associate professor of English and co-director of the creative writing program at Brandeis University. She spends time every year working as a naturalist and guide in the high latitudes of the Arctic and Antarctic.

And this, too: Bradfield is a collaborator, receiving and spreading energy along the way. She recently worked with visual artist Antonia Contro to create a hand-bound letterpress book, Theorem, published by Candor Arts in an edition of only 30 copies. She describes it as a “conversation between text and image, mapping a journey back in time.”

And Bradfield is the founder and editor-in-chief of Broadsided Press, a monthly collage of literary and visual arts consisting of poems and flash-fiction that are selected from submissions and forwarded to a pool of artists, who create a painting, a sculpture, or a photograph as a visual response. Outer Cape artists Bailey Bob Bailey, Janice Redman, and Karen Cappotto have been contributors. The paired result is a “broadside” — a pdf emailed to grass-roots “vectors” who print and post it where they live.

“It’s like sending out little carrier pigeons,” Bradfield says. “There have been 300 or so broadsides by now.” She plans on self-publishing a “best of” Broadsided later this year.

Bradfield grew up in Tacoma, Wash., and spent three weeks each summer traveling up and down the northwest coast, vacationing with her family. A literature and women’s studies major at the University of Washington, she was all set to go to graduate school when a job as a deckhand came up, so she spent a year on small eco-tour ships, traveling back and forth from Alaska to Baja California.

“That changed me totally,” she says. “For me, there’s always been this parallel course, a real love of boats and natural history, and a love of books and words.”

She eventually got an M.F.A. in literature from the University of Alaska, and after a romance that began when she was a deckhand on a boat in Baja and met the naturalist guide on board who was familiar with the Cape, Bradfield packed up and moved, landing in the wilds of Truro.

You can experience her talents as a poet-naturalist this Saturday morning in a guided walk on the dunes and marsh of Hatches Harbor in the Cape Cod National Seashore in Provincetown, along with Center for Coastal Studies biologist Lisa Sette. Registration is required with CCS.

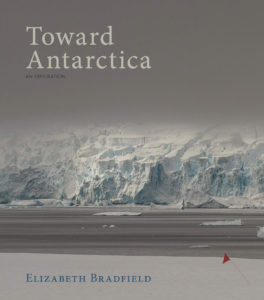

Or pick up a copy of Toward Antarctica: An Exploration at a local library or bookstore. Published last May by Boreal Books, an imprint of Red Hen Press, it’s Bradfield’s 150-page personal travelogue through the frigid yet fertile polar landscape. Readers who enjoy poetry’s associative connections can linger over her approach to the classical Japanese haibun form — diary-like prose combined with short poems. Color photography (she uses a digital SLR with a 400-mm lens, as well as a point-and-shoot camera) supplants the form’s traditional calligraphy.

“I am not a quote, unquote wildlife photographer,” Bradfield says. “My goal was never to publish in National Geographic. For this book, I chose images that were evocative and surprising to me. There’s information, and then there’s emotion. I am very interested in photographs that somehow transcend their digital origins to feel truly personal.”

One of the dangers of eco-tourism is habitat degradation, with humans as the invasive species. “There was never an indigenous human population in the Antarctic, making the place totally unique on the planet,” Bradfield writes, and she describes in the book searching passengers coming aboard for even small things like seeds hiding in the cuffs of pants: “A crew finds a seed in Velcro, plucks it out. Shouts ‘One saved albatross!’ Parka, pack, gloves, hat, walking stick. Ten coats later another grass seed — ‘One saved albatross.’”

In a blue-gray photograph of Point Wild, Elephant Island, penguins preen and nap in the shadow of a monument. “It was on this toenail of land that Sir Ernest Shackleton’s crew waited 137 days for ‘the boss’ to return and rescue them,” Bradfield writes. Though Shackleton was involved in the rescue, the crew was first found by the Chilean captain whom the monument honors.

In another image in the book, a cove is packed with the seals that were once hunted close to extinction for their fur coats. “Today, they are formidable and amazing,” Bradfield says. Given time, and limited human intrusion, nature can rebound.

In response to a question about environmental changes on the Outer Cape, Bradfield says, “Preparing to travel to the Arctic, I realized there is plant life on the Outer Cape similar to what I was to experience. There is the bareness and fragility of the sandy soil. And, of course, there is the fragility of Cape Cod from climate change, causing storms and rising sea levels. It’s a through line everywhere.”

Walking the Line

The event: Guided walk with poet-naturalist Elizabeth Bradfield and Center for Costal Studies biologist Lisa Sette

The time: Saturday, Feb. 15, 10 a.m.-1 p.m.

The place: The dunes and marsh at Hatches Harbor in Provincetown

The cost: $25; pre-registration is required: call Lisa Sette at (508) 487-3622, ext. 101