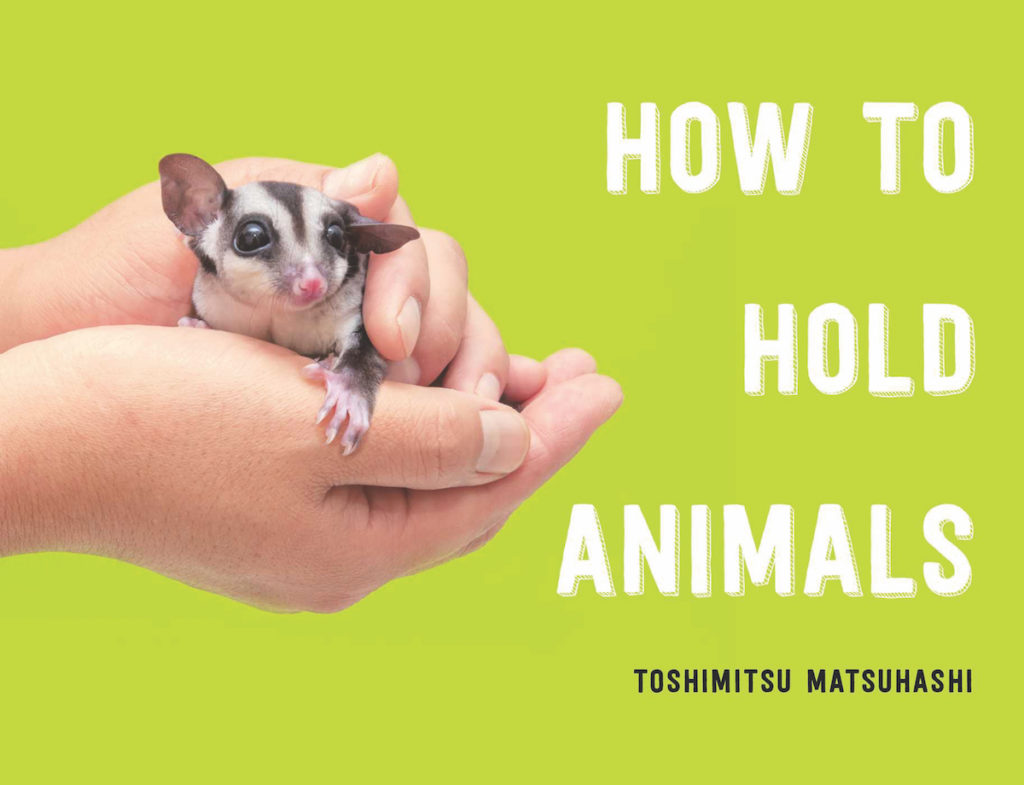

The cover of Toshimitsu Matsuhashi’s How to Hold Animals features an adorable sugar glider, a bug-eyed mouse-like creature, gently cupped between two human hands. Readers might therefore expect the book — elegantly translated by Angus Turvill from the Japanese, and published by Scribner in November — to be adorably kitschy in the manner of Sanrio’s Hello Kitty. But betwixt its rectangular, avocado-green covers, this delightful small book abounds with wonderful photographs, practical advice, and disarming humor — not a bit of kitsch.

Matsuhashi was a keeper at one of Japan’s largest aquariums before becoming a professional animal photographer. An avowed lifelong animal lover, he advocates for children’s direct interaction with the natural world. He has found, over the years, that educators interested in wildlife conservation frown on children catching wildlife. “Instead of talking loftily about animal protection,” he writes, “I’d rather pick an animal up, show it to children, and give them some practical advice.” The trick to opening minds and developing a reverence for nature, he reasons, is in knowing a thing or two.

Though children will love looking at the many wonderful color photographs in the book, they aren’t Matsuhashi’s target audience. He has written the book to educate older readers in correct holding techniques, mostly with an eye towards avoiding being bitten, stung, scratched, or squeezed to death. Matsuhashi interviews and photographs three experts — a veterinarian, pet shop owner, and reptile shop owner — whose insights he includes in addition to his own.

In each of the four sections, an expert models and describes handling techniques, offering nuggets of wisdom. For example, Tokyo veterinarian Kenichi Tamukai says that about 80 percent of his job is knowing how to keep animals still. He relies on what he calls “Hold Spirit — a state of mind that helps me keep an animal still and safe in an appropriate way.” Matsuhashi advises against picking up anything and everything, because some creatures just aren’t safe. “Admitting you’re not sure is sometimes the brave thing to do,” he writes.

If readers don’t want to pick up a certain creature just because it is stinky or slimy or scary, Matsuhashi creates scenarios intended to encourage. Take cockroaches, for example. He writes, “ ‘No way am I picking up one of those,’ you may say, but then how are you going to protect your home from these noxious pests?” Then there are the hypotheticals, a key element of which seems to be fear of shame. “Imagine you’re in love with someone who works in a pet shop,” Matsuhashi writes. “You’re in there one day pretending to browse, when a chinchilla escapes. Your crush asks you to catch it…. Obviously you want to look cool and competent. So be prepared. Now’s your chance to learn how to handle a chinchilla.” He provides similar admonitions when it comes to hamsters, tarantulas, and all manner of lizards and snakes.

Many of these animals are, not surprisingly, difficult to catch and handle. Lizards, for example, are not “morning people.” Matsuhashi advises readers to be on the lookout before 7 a.m. in the summer and before 9 a.m. in the fall and spring, when the creatures venture out to warm themselves in the sun. They are relatively slow as they warm up, making them easier to grab and hold. But what to do once you’ve captured it? There are step-by-step instructions, with close-ups of hand and arm holds.

There’s advice about plenty of creatures Outer Capers will encounter throughout the year, including grasshoppers, crabs, turtles, terrapins, snakes, slugs, chipmunks, beetles, butterflies, dragonflies, and praying mantises. As for the last, Matsuhashi describes mantises as particularly “tough” and “uncompromising.” Though they may look cool and elegant, their kicks pack a punch. “If it were the size of a cat, you wouldn’t stand a chance,” he writes. “If it were the size of a human, it would rule the world.” How to avoid injuring mantis or man? Hold the thorax and leg joints at the same time.

Matsuhashi suggests readers carry his book with them wherever they go, because, well, you just never know when you might need to capture an owl that’s flown inside a building. Or when you might need to clip a hedgehog’s nails. Or get a brightly colored, screaming gecko out of your expensive vacation rental in Southeast Asia. I am imagining my own hypothetical, which includes a paperback version, a suitcase in which to tuck it, and a destination far, far away. For now, I’ll just use the helpful index to prepare.