Nature isn’t always natural, suggests the Fine Arts Work Center’s summer exhibition, “To Move a Mountain.”

Coady Brown, an artist who curated the work by nine former FAWC fellows, writes in the exhibition statement about flowers as romantic symbols. She includes one of her own flower paintings in the show — a simple bouquet against a background the color of a faded yellow highlighter. The synthetic color and Brown’s stylized brush stokes divorce these flowers from nature. Jagged forest-green shapes describe leaves, but they are not a realistic description of foliage. These leaves and flowers belong more to the language of abstraction and painting — the domain of culture.

Of course, many aspects of nature — including flowers, vegetables, parks, and animals — have long been controlled, domesticated, and poeticized by humans. This exhibition highlights that mediation and suggests that when we look at an artwork depicting something from the natural world, we’re not really seeing nature in any pure sense but rather a reflection of our culture.

The exhibition, spread across two rooms in the Hudson D. Walker Gallery, is sparse. Colorful paintings dominate, but there is also sculpture, photography, and drawing. The first room is anchored by two large-scale works, a painting by Dani Levine and a charcoal-and-pastel drawing by Alina Perez. Both works are landscapes, in a sense, but their colors are decidedly synthetic. The landscapes in these paintings are not records of specific places but rather springboards to explore sexuality, kitsch, and abstraction.

Perez’s painting depicts a sleeping mermaid with her head resting in the lap of a nude woman. The setting sun, aqua blue water, and roses in the foreground knowingly evoke a kitschy, sentimental visual language — the sort of thing you might see airbrushed onto a beach towel. Perez’s soft touch and her use of pastels further this association. The idealized curvy figures of the two women belong to a similar world — they’re more pinup girls than observed bodies. The elements of this picture are codes of human aspirations for escape and fantasy.

Levine’s painting is nearly abstract, but there’s reference to the landscape in a patch of blue sky and a shape that arises like a sail. For Levine, the landscape is an armature to explore material concerns — each element of this painting is created with carefully chosen pigments, mediums, and grounds to evoke different qualities of airiness and density.

Like Perez and many other artists in the exhibition, Levine also uses the landscape as a setting for asserting identity. The orange shape rising upward is an abstracted labrys, a double ax adopted as symbol of lesbianism. It’s her sail — or flag — planted in the landscape.

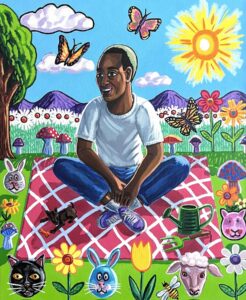

Cheyenne Julien and Lamar Peterson also insert depictions of their communities in bucolic settings, subverting the notion of the pastoral as a white space. Peterson’s painting belongs to a recent series by the artist depicting black men in gardens. In Untitled, a man sits cross-legged on a blanket in the grass surrounded by flowers, mushrooms, butterflies, and images of animal’s heads. Purple mountains lie on the horizon; fluffy clouds and a cheerful sun hang in the cerulean sky. The high-key color, flattened space, and outlined objects suggest coloring books and children’s drawings. In this painting, the garden is a product of the imagination — a cultivated space of innocence and escape — and a cultural domain where Peterson’s African American men can rest, free from any cultural expectation of them as urban and beleaguered.

Julien is an artist living and working in the Bronx. In her figurative paintings and drawings, she uses humor, exaggerated features, and dramatic color to comment on urban life. In her painting in this exhibition, she depicts a curvy woman in a thong bikini from a low angle — basically, a booty shot. She’s painted in black and white, but the background is an explosion of colorful flowers and psychedelic swirls. Like Peterson, Julien is bringing someone from her community into the garden, but the statement here is more uneasy, the connection more tentative and humorous.

In Sno Cones for Us … Sno Cones for You …, Pat Phillips melds a variety of painting and drawing languages in a collage-like composition. Echoing Peterson’s work from across the room, this painting has a pair of flat, cartoonish characters but also realistic renderings of chairs and oversized hands drawn with charcoal. The spirit of collage runs through this exhibition, although none of the works is an actual collage. Widline Cadet’s image of two hands holding a bouquet of flowers uses flash photography and a patterned backdrop to create a stilted, artificial connection between the elements in the image, in much the same way that Brown paints each flower in her bouquet with a distinct gesture, thereby eschewing any sense of a unified whole.

In Phillips’s painting, artifice reaches a climax. We’re in the suburbs here, nature has been eclipsed by the synthetic, and it’s not pretty: the painting, which appears to be made on a stained dropcloth, is littered with images of plastic and metal chairs, empty pizza boxes, a shopping cart, and the ultimate consumerist perversion of anything natural and nourishing: sno cones.

If Phillips’s work is at one end of a spectrum ranging from the natural to the artificial, Raul De Lara and Anina Major are at the other end. Their pieces, more than any other in the show, feel earthy and relatively free from intrusions of human culture. De Lara used walnut and oak to create a sculpture of an oversize leaf. The circular grain of the wood mirrors the leaf’s organic shape, and there’s a clear parallel between the subject and material — both are sourced from trees. But look closely, and you’ll notice the leaf is affixed to the wall with a wooden bolt. Industry can never quite escape the frame.

Major’s ceramic sculpture Solitude hangs about two feet from the ground, suspended by rope and a chain from the ceiling. The spiky ball looks like a giant sea urchin. It’s covered with glazes in earth colors — white, black, grayish blue, and yellow ochre — that drip down the way water might fall from an object arising from the sea. That feeling of it lifting from the sea is also suggested by the rope, which transitions from blue to white as it stretches upward, holding the sculpture like it was caught in a net.

The suspension of Major’s sculpture — both physically and metaphorically — encapsulates the tension between nature and artifice in this exhibition. These objects come from the natural world but can never really belong to it. They’re suspended above it, maybe reflecting something of nature but only through the lens of human culture and creativity.

Unnatural Nature

The event: “To Move a Mountain,” group exhibition of former FAWC fellows

The time: Through Aug. 22

The place: Hudson D. Walker Gallery, Fine Arts Work Center, 24 Pearl St., Provincetown

The cost: Free