Henry David Thoreau arrived in Provincetown on his third visit to Cape Cod on July 5, 1855. He had sailed from Boston on the schooner Melrose, and the next morning he took the stage to North Truro, where he boarded with Keeper James Small at Highland Light. There, the ever-curious Thoreau made observations in his journal and enjoyed the company of many Truro inhabitants.

One local whom he wrote about he called Peterson, though that was not a common surname in Truro. On July 9, Thoreau noted, “Peterson brings word of blackfish. I went over and saw them. The largest about fourteen feet long.” On July 12: “Peterson says he dug one hundred-and-twenty-six dollars’ worth of small clams near his house in Truro one winter, twenty-five bucketfuls at one time.”

Peterson was John Peterson, born in Boston in 1801. A carpenter by trade, he was in Truro by the summer of 1821. That’s when he married Elizabeth “Betsy” Gross Lombard, from one of Truro’s well-known families. She was the widow of Thomas Lombard, lost at sea in 1819 and with whom she had three daughters. With John Peterson, she had five more children, Thomas Lombard, John, Emily, who died in infancy, a second daughter named Emily, and Elisha.

When Thoreau arrived, Truro was likely still abuzz with news of a heroic rescue two days earlier. On the morning of July 4, 1855, a sailing party of two young boys and six young girls had been run down by another boat, the crash spilling the eight children into the water. Among those on nearby boats were 22-year-old Elisha Peterson, who was, like his father, a carpenter, and John Shay. Both dove into the water. Newspapers reported that “almost by superhuman exertions,” the two succeeded in saving all eight children, three of whom were rescued from the bottom. Later that year, Elisha married Sarah Atwood.

For John and Betsy Peterson, it was a bright moment after some dark times. In February 1829, the Petersons’ one-year-old daughter, Emily, died. A year later, a second daughter whom they also named Emily — a common practice at the time — was born. She married Joshua Small Jr. in February 1847. Their infant daughter died in March 1848. Then, in early 1850, Emily died of consumption (the bacterial infection we now know as tuberculosis). A month after that, Joshua drowned. In October 1850, their eight-month-old son, Joshua, died, also of consumption.

Nine years earlier, in 1841, Truro families grieved the loss of 57 men and boys during an October gale. The Petersons shared that grief, having lost their 17-year-old son John aboard the schooner General Harrison. Thoreau had visited the obelisk in the Congregational Cemetery that memorializes the lost mariners, recording its inscription in his book Cape Cod, and one might wonder if, after making the acquaintance of John Peterson, he had spoken with him of the tragedy. Thoreau seemed to anticipate such speculation, writing that he “found that it would not do to speak of shipwrecks there for almost every family has lost some of its members at sea.”

The eldest of the Peterson children, Thomas Lombard, was born in August 1822. In May 1847, he married Ruth Atkins Hughes, the daughter of Atkins Hughes and Jerusha Dyer. (After Atkins Hughes was lost at sea in 1828, Jerusha married James Small, the keeper of Highland Light, with whom Henry David Thoreau had lodged.)

Thomas and Ruth welcomed their first child in 1848, a daughter they named Emily.

Ledgers from the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital, a floating hospital on the Thames at Greenwich, England that provided medical care to merchant seamen from across the world, show that Thomas Lombard Peterson was admitted in March 1849 for 10 days with a fever. The record indicates that Peterson, then only 28, already had 13 years of merchant service.

He must have recovered fully, because between 1851 and 1856, Thomas and Ruth had three more children together. Then, in July 1858, Thomas’s life took a baffling and scandalous turn.

Newspapers reported the “elopement” of Thomas, then 36 and still married to Ruth, with an 18-year-old Truro girl named Huldah Atwood. The daughter of Richard and Tamsen Atwood, who were described in the papers as respectable parents, Huldah was said to be quite pretty and had “hitherto borne a character for extraordinary steadiness and sobriety.”

Complicating matters for the Peterson family, Huldah was the sister of Thomas’s brother Elisha’s wife, Sarah.

Thomas had raised money on a promissory note endorsed by several of the “solid men” of Truro, and with it, he’d left town with Huldah, bound for California.

Both Thomas and Huldah apparently came to their senses after a time. They returned to Truro, where Huldah would later marry. By December 1861, Thomas and Ruth had welcomed their fifth child, Alice. Just a few months later, in April 1862, Thomas Peterson enlisted in the Union Navy, his merchant service qualifying him as an acting master, a temporary commission for volunteer officers to meet the wartime demand.

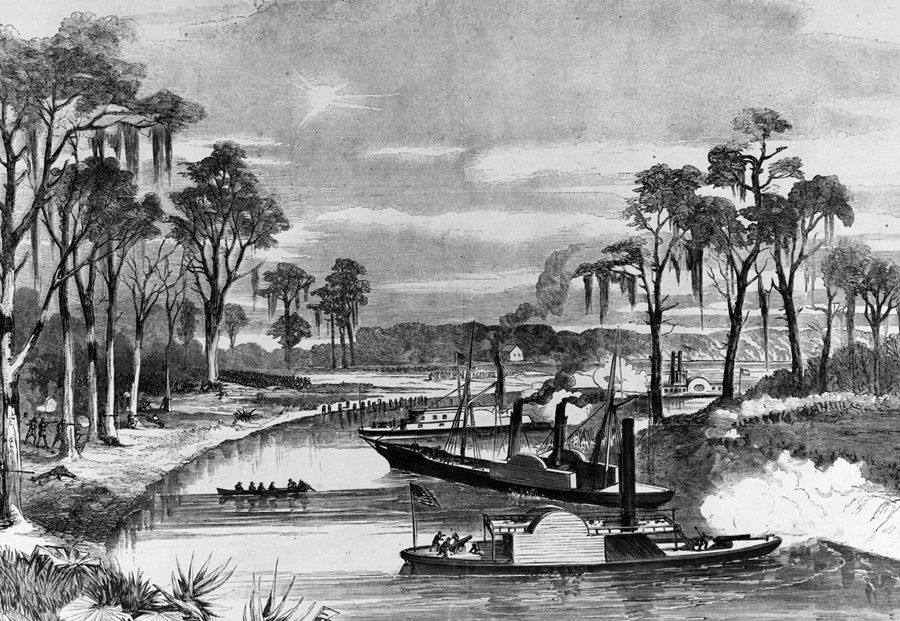

On March 1, 1863, Thomas Peterson became commander of the USS Diana. Originally a civilian sidewheel merchant steamer, the vessel was captured by the Union Navy at New Orleans in April 1862. First used as a transport on interior waters, she was later outfitted as a gunboat and took part in engagements with the Confederates, notably at Corney’s Bridge on the Bayou Teche waterway in Louisiana in January 1863.

On March 28, 1863, while on reconnaissance, Diana was disabled by Confederate shore batteries on the Bayou Teche at Pattersonville and recaptured. Among the six who were killed during the engagement was Thomas L. Peterson. His headstone in Snow Cemetery remembers his Civil War service, though Truro historian Shebnah Rich suggests that Peterson was buried in Morgan City, La.

Elisha Peterson, who had heroically saved the children on that Fourth of July morning, was the only child of John and Ruth Peterson to outlive his parents and live to old age. Widowed in 1874, he lived for many years in Portland, Maine, where he established himself as an expert cabinetmaker and skillful billiardist. He died in 1922, survived by three of his five children, and is also buried in Snow Cemetery.