Last summer, I received an intriguing Instagram message: “Hi, my name is also Saskia, but that’s not why I’m messaging you. I was Googling and came across your article on my great aunt, Thelma.”

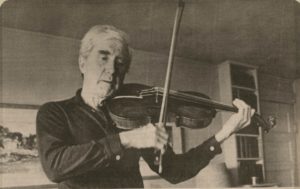

This was nearly a year after I wrote “Discovering Thelma Given, Provincetown’s Paganini” for the Independent. The genesis of the article was a rare recording on the Provincetown History Preservation Project’s website. I learned how Thelma Given, once a violin prodigy, made a name for herself as a female soloist during a time when that was exceptional.

It’s not every day that I meet another Saskia, so, when she was visiting family on the Outer Cape, we had tea. Saskia van Vactor, an artist and teacher, told me how both Thelma and her grandfather Eben, an artist, were “larger than life.” They spun a lot of tales, probably not all true.

For example, Saskia told me Thelma’s version of a story related somewhat differently in my earlier article. Thelma claimed that when she was studying with Leopold Auer and the Russian Revolution broke out, she wrapped her violin, purported to have belonged to Paganini, in baby clothes and escaped to England on a dog sled. I thought of that scene in The Living Daylights when James Bond and Kara Milovy escape on a sled made from her cello case.

When doing research, it’s easy to forget that historical figures were once living, breathing people.

When I was writing “Provincetown’s Forgotten Symphony Orchestra,” Nancy Dickinson told me she remembered her father, the conductor Joseph Hawthorne, recording performances of the Provincetown Symphony in town hall with a microphone. I hoped such a recording would turn up.

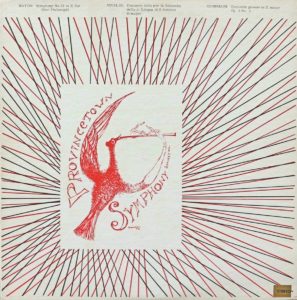

Sure enough, soon after the article ran in November 2020, I received an email tip from Independent reader Will Walker, who told me his friend Dana Berry had found an LP of the Provincetown Symphony years ago at the Orleans thrift shop. (This turns out to have been a steal, as the same early 1960s recording is selling for $400 on eBay.) The two grew up being dragged to Provincetown Symphony concerts by their parents.

After a handoff, I was able to finally listen to the orchestra play an ambitious program: Haydn’s “Philosopher” Symphony, a concerto in D major by Vivaldi, and Francesco Geminiani’s Concerto Grosso in E Minor. The recording, though scratchy, reveals world-class playing.

The adagio first movement of the Haydn has a good tempo, dignified without getting bogged down. The presto second movement is sprightly, whereas the minuetto third movement sounds a little too deliberate. The horns sound superb in the presto finale.

The Vivaldi is far from historically informed, though there is a harpsichord. The steely bass section sounds dark and murky, but very of its time. Violin soloist Gerald Tarack is agile and resonant in the allegro first movement. There are some cello intonation problems in the largo second movement, but the whirring allegro third movement has a great violin cadenza.

Geminiani is an unusual choice. The adagio first movement, leading to the fugal second movement, sounds ponderous. There are interesting harmonies in the yearning adagio third movement. The allegro fourth movement is full of energy. And while the orchestra seems more comfortable playing Haydn than the Baroque composers, the programming is admirable.

When I wrote my article on the Provincetown Symphony, I didn’t know of any surviving members. Since then, I’ve found one: Philip Dunigan, a flutist, now in his late 80s and living in North Carolina. In the 1960s, he was living on Cape, having married into the Malicoat family. (His daughter is the artist Breon Dunigan.)

Dunigan was able to confirm that the orchestra brought in ringers from New York City. He says the series started off as a couple of summer concerts in the summer before expanding. Dunigan remembers fondly playing a Boccherini concerto with renowned cellist Bernard Greenhouse. There was also chamber music at the Provincetown Art Association.

“Jo Hawthorne was a wonderful musician, but not a gifted conductor,” Dunigan admits. “You see, there are conductors, and there are instrumentalists. We had great respect for him and would do everything we could to help him out.

“Even so, he got better results than a lot of people who looked really good waving a wand,” Dunigan continues. “He knew an awful lot and was really ace at programming.”