People have always felt free to say whatever they want about Britney Spears’s personal life. This was true at the beginning of her career when she was in her teens and 20s and her every move was followed by the paparazzi and fanned out in the tabloids. It was equally true in 2021 when friends, former employees, and anyone who had once brushed shoulders with Spears talked to Fox, CNN, the New York Times, and the New Yorker about Spears’s conservatorship. Because of that conservatorship, the only person who was not allowed to speak freely on the subject of Britney Spears was Britney Spears.

A conservatorship — if you haven’t seen any of the three documentaries on the subject yet — is a legal structure in which a guardian is given decision-making power over another person’s legal, financial, medical, and even personal affairs. In 2008, Spears’s father, Jamie Spears, had her admitted to a psychiatric ward in Los Angeles after a series of public meltdowns that are now widely considered to have been caused by postpartum depression. The next morning, with Spears still in the hospital, her father went to court and, after a 10-minute hearing, was granted a conservatorship over Spears.

Conservatorships are intended for people who are incapable of taking care of themselves because of physical or mental limitations. During the 13 years of her conservatorship, Spears released four mega-selling albums, went on a world tour that grossed over $100 million, and held down a four-year residency in Las Vegas, where she also taught twice-weekly dance classes to children. All the while, Spears was making a lot of money for a lot of people, including her father, who, with full financial control of the Britney Spears empire, took a bigger salary for himself and many others than the “allowance” he gave his daughter.

The three documentaries and a long New Yorker article were contemporaneous with Spears’s first successful attempt at getting the terms of her conservatorship discussed in open court. Spears was an extraordinary victim of conservatorship abuse, a crime that is more common than you would like to think. The filmmakers and journalists were trying to help her tell that story, even though they couldn’t consult Spears herself, who, under the conservatorship, was not allowed to speak to the press without her father’s approval.

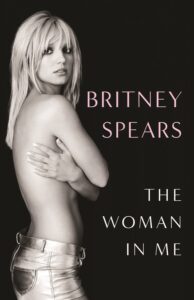

“Seeing the documentaries about me was rough,” Spears writes in The Woman in Me, her memoir, published by Simon & Schuster last month. Outside of social media, the book is her first public statement since she freed herself of the conservatorship more than two years ago.

The Woman in Me is, in many ways, a less detailed account of the conservatorship than previous reporting. Whereas the New Yorker, in thousands of words, explained exactly how the conservatorship was established, Spears spends only a few hundred. She does not offer the ins and outs of how exactly, in 2008, her father gamed the legal system and colluded against his own daughter. But how could she? She was sedated in a hospital when all that happened. The wool was pulled over her eyes. The memoir reader experiences the whiplash of waking up one morning to realize that your life is no longer your own.

Spears learned this harsh news a few days after the conservatorship took effect when her father walked into her hospital room, folded his arms, and said, “I’m Britney Spears now.”

A few days later, back at the house that Spears had bought for her family when she was just a teenager, Jamie told Britney that she had gotten fat and that he would get her a personal trainer and put her on a new diet. Jamie pointed at the TV and said, “You see that TV over there? You know what it’s going to say in eight weeks? That’s gonna be you on there, and they’re gonna say, ‘She’s back.’ ”

Spears is subjected to daily weigh-ins, two-hour training sessions, and calorie tracking. When she wants to try to have a third child, her father won’t let her see a doctor to take out the IUD he had made the decision to implant in the first place. When she first attempts to challenge the conservatorship in court, her father warns her that she will be made to look like an idiot in court: “Trust me, you will not win,” he says.

Spears’s tone is not one of pity for herself but of shock that other people could be so evil. She frequently attests to her Christianity (almost as frequently as she avows her love for the LGBTQ community), and her pity finds its focus not on her past but on the fate of her abusers’ souls.

“It just wasn’t nice,” she writes more than once of behaviors that other people would describe as diabolical, vile, and criminal. Her aim seems not to be retribution but a plea for decency.

Spears’s life has been read, since she was a teenager, as a parable for how a young woman should and should not behave. Her body has been mapped as the battleground where Americans could hash out their feelings about what counted as beautiful, their anxieties about their teenage daughters’ sexuality, if getting breast implants made you a bad person, and what weight counted as healthy. Amid this proliferation of chatter — which took place in magazines, on morning talk shows, around dinner tables, in minivan arguments between daughter and father, and increasingly on the internet — the only person who was not allowed to partake was Spears. Now, she has her chance. And what she has to say is somehow far more graceful than any other commentator has been to date. It leaves you with a hush, both ominous and serene.