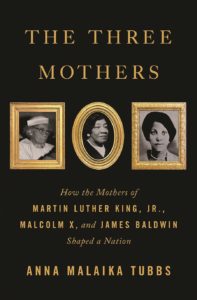

It is easy to pan Anna Malaika Tubbs’s The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation, released last month by Flatiron Books. It is also easy to praise it. Each stance has roots in different academic and activist communities, which may or may not be at odds with one another. It’s hard to know, in this particular political moment of racial reckoning and Black Lives Matter, which one deserves more weight.

First, the pans: Tubbs claims, in her introduction, that she has uncovered “fascinating facts” to “provide incredible new depth” and “invaluable new knowledge” about Alberta King, Louise Little, and Berdis Baldwin, the mothers of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin, respectively. But there is little new to the stories Tubbs tells about each of these three mothers, whose sons shaped the civil rights movement and about whom much has been written.

Unlike Isabel Wilkerson, for instance, whose 2010 history of the Great Migration, The Warmth of Other Suns, won prizes for original research and lyrical writing, Tubbs does not document her historical sleuthing and writes repetitively and blandly. She describes a process drawing on extensive archival research and interviews, but her lack of footnotes makes it impossible to evaluate which discoveries are original. Though she includes a bibliography, there is no separate section for manuscript collections. As a result, when Tubbs refers to letters between mothers and their famous sons, there is no way for readers to find or read the primary sources themselves. Tubbs periodically relies on intuition and speculation. For example, she writes “I like to imagine that” when describing possible experiences of West African ancestors.

Tubbs’s lack of distance from her subjects will make some readers uncomfortable. She begins The Three Mothers with an anecdote about attending Frederick Douglass’s bicentennial celebration with her husband. She writes of the off-white dress she wore, her anxiety around an overdue menstrual period, and a trip to the drugstore to purchase a pregnancy test. She uses the story to explain that pregnancy and parenthood took on new meanings for her as she continued research on Black motherhood for a Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge. Throughout the book, Tubbs uses the personal plural pronoun “we” — as in “we Black mothers” and “we Black women and our children” — to create a sense of intimacy between herself, her readers, and her subjects. She also refers to her subjects by first name throughout. This choice could be political, but without an explicit explanation, it may seem overly chummy.

Now, the praise: Tubbs declares her anger that “the three mothers who birthed and reared” Martin Luther King Jr., James Baldwin, and Malcolm X “have been erased,” especially when historians have credited the fathers for setting the sons on important paths. She aims to give these three women — and, by extension, all Black women — affirmation, especially in the face of generations of dehumanization. Tubbs is careful not to use motherhood as a substitute for relevance. She depicts all three women as intellectually gifted, independent, and capable of self-determination in the face of structural racism, violence, and misogyny.

Alberta King, Berdis Baldwin, and Louise Little were born within six years of one another and gave birth to their famous sons within five. They were smart, fierce, and fearless. Their lives spanned the major moments of the 20th century, including both world wars, the Great Depression, Great Migration, Harlem Renaissance, and Jim Crow. Tubbs uses details from their lives to help narrate movements and events, providing nonspecialists with a good, if general, introduction to 20th-century Black history.

By situating what is known about King, Baldwin, and Little in larger contexts, Tubbs is able to show how these mothers taught their sons to refuse “to acquiesce to the notion of their supposed inferiority.” Their resistance, she explains, escapes historical notice without a radical reframing through the lens of Black feminism. “We cannot understand the Littles, Kings, and Baldwins,” she writes, “without understanding African American history as well as the unique backgrounds of both parents heading the household.”

Tubbs makes sure, as she recounts these histories, to tackle negative Black female stereotypes, including so-called “pickaninnies,” “jezebels,” “mammies,” “matriarchs,” and “welfare queens.” Her analysis negates such demeaning and untruthful depictions, which, she writes, are “meant to misrepresent them and ignore the factors contributing to their victimization.”

There is a tendency, in white supremacist culture, “to identify what is wrong” without an “ability to identify, name, and appreciate what is right,” Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun write in Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change. One antidote, they explain, is to “develop a culture of appreciation” where people’s work and efforts are respected.

A book critic’s job is to contextualize so that readers can appreciate an author’s accomplishments as well as her missteps. Given that Tubbs writes that she is working to dismantle white supremacist culture, it’s hard to know whether academic standards of supposed objectivity and documentation are relevant. Readers searching for a purely scholarly treatment may find Tubbs’s book wanting. But readers, especially younger ones, looking for an accessible celebration of Black motherhood in spite of American racism and sexism may take great pleasure in learning more about the lives of these three remarkable women.