Sometime in the last year, as one does in a pandemic, I began cleaning drawers. Among the items that I found were unopened packets of seeds. Columbines I’d bought when visiting family in Colorado. Carrots and green beans from a seasonal kiosk at the Provincetown Stop & Shop. A paper envelope with the following written in my own hand: “TOMATO SEEDS. JIM. 2016.”

A gifted organic gardener, Jim had shared his delicious heirloom tomatoes with me. He told me to save the seeds, dry them on a paper towel, tuck them away, and plant them next year. I didn’t forget about those seeds, but I didn’t plant them.

Like so many, I aspire to grow a garden, but I never seem to get very far, especially when it comes to things to be eaten. Coming across the seed packets this year — the envelope of Jim’s tomato seeds in particular — made me want to try again. I ordered five packets of hearty varieties by mail: French breakfast radishes, bok choy, a mustard hybrid, napa cabbage, and shiso (also known as perilla green). And then I froze.

As is often my strategy, I turned to research. “If I just knew more,” I thought to myself, typing the terms “low-maintenance,” “raised bed,” “easy,” and “beginner” into the search bar on the Wellfleet Public Library website. I collected brown paper bags full of requested volumes. Low-maintenance turned out to be anything but. Some manuals dove so deep that I feared I’d never emerge. Others intimidated me with their assertions of competence, polish, and expertise. I was on the verge of stowing seeds in a drawer yet again.

And then I opened Jessica Sowards’s The First-Time Gardener: Growing Vegetables, published in March. Sowards diagnosed head-on my gardening (and life) hang-up. Like her, I was suffering from “analysis paralysis.” More than once, she explained, the condition — as much as blossom-end rot or cabbage moths — had deep-sixed her gardens, because she didn’t plant the seeds “for fear of doing it wrong.” She learned to throw caution to the wind and simply try. “A planted garden,” she writes, “is always better than a perfect plan for an unplanted one.”

Sowards suggests a radical embrace of failure and learning as an antidote to such paralysis. A garden can be a classroom, a place to be imperfect, messy, inexact. Seeds want to grow, so all we really need to do is harness their energy. Her refreshing approach and the book’s unfussy layout beckoned me to get out of my own way.

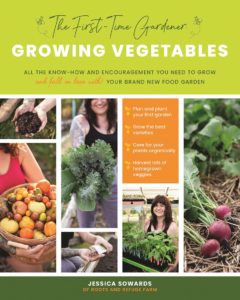

The book is divided into eight succinct chapters, as well as an introduction and conclusion. Large color photographs showcase the vegetables that Sowards, her husband, and their six children grow on Roots and Refuge Farm in central Arkansas. Each chapter begins with an encouraging quote, such as this one from Rudyard Kipling, at the beginning of the chapter “The Nitty-Gritty of Garden Management”: “Gardens are not made by singing, ‘Oh, how beautiful and sitting in the shade.’ ”

A natural teacher, Sowards simplifies concepts such as soil management, growing season lengths, distinctions between heirlooms and hybrids, and organic pest control methods. She evaluates the relative merits of raised-bed versus in-ground gardening, giving pros and cons. Her publisher, Cool Springs Press, specializes in heavily illustrated how-to guides. Sowards has included easy-to-read charts, bulleted lists, and plenty of two-page spreads showcasing specific steps. How to get sprouted seeds into the ground without killing the plants? Photos of Sowards’s tattooed arm and earth-covered hands demonstrate hardening and transplanting seedlings into the welcoming, dark soil.

Sowards is also a gifted writer. Her words bring the many acts and facts of gardening to life and illustrate her principles as vividly as her photographs. Don’t follow seed packet or garden store rules about planting dates, she advises. Instead, figure out what works in the particular spot you happen to be gardening. She broke those rules and planted early, noticing that when others were tilling and preparing plots, “I already had rows of peas climbing a makeshift trellis, radishes crying out to be picked, and happy bunches of kale stretching their arms to the sun.”

Sowards is open about her Christian faith and its role in her life and gardening. A self-described “vlogger,” she has a popular YouTube channel where she frequently shares content about her marriage, her church, and her agricultural pursuits. She also contributes to Do South, an online magazine, where she calls herself a “homesteader” and “regular Arkansas girl.” A 2017 article on “hipsteaders” in Bon Appétit magazine identified Sowards as part of a movement of Instagrammers who “steer clear of politics and current events on their accounts, except to imply that their lifestyles are an antidote to everything that’s wrong in the world.”

I haven’t sampled enough of Sowards’s media content to evaluate whether this is true. But I am uplifted by her desire to share an approach that puts the fragility of people and planet at its center. She focuses on the ecumenical possibility of choosing to begin again: “As we part ways at the end of the pages, I offer you one last piece of advice: Repeat after me, ‘There is always next year.’ If you want to really drive it home, say it with a shrug of your shoulders. … There will always be another garden as long as you choose it.”

Even as I type these words, my husband is laying down pea gravel and setting up hoses so our new raised bed will stay damp while we come and go from Wellfleet. The seeds are going in the ground mid-May. I will plant them.