Residents of and longtime visitors to Truro are surely familiar with a grisly, dark chapter of the town’s recent past involving Pine Grove Cemetery. Even now, decades later, just reading about the bloodcurdling events of January 1969 might be enough to dissuade many from venturing into the secluded burial ground. It would, however, be a shame to bypass this tranquil two-acre spot, filled with bird song, and tucked amid the scrub pine of the National Seashore down a dirt road off Old County Road.

Pine Grove is Truro’s second oldest cemetery (Old North Cemetery being the oldest), created in 1799 by Methodists near a church (established 1794) that no longer survives. In 2013, the cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Here you’ll find not only an eclectic mix of stones — from early slate to modern — that memorialize prominent Truro families (the Riches account for nearly one third of the burials) but yet another compelling Truro story from the town’s more distant past.

By all accounts, Sept. 15, 1844 — a Sunday — dawned crisp and clear, a perfect early autumn day. Behind the dune that protected the bustling and prosperous village of 2,000 residents from Mother Nature’s ferocity, townspeople attended church and returned to their homes for an afternoon of quiet reflection before retiring for the evening.

As Monday dawned, crews leaving the Pamet Harbor and heading out to sea saw the mackerel schooner Commerce anchored not more than a mile off the Truro shore. It was assumed that the crew of 10 had come ashore in the longboat during the night. As news spread that the Commerce crewmen were not yet at home with their families, several townspeople reported that they had, in fact, seen the Commerce at anchor early Sunday morning, though none of the crew had been present at church, as would have been customary. Alarmed neighbors rowed out to the schooner and found it meticulously secured, but with no sign of life. The whereabouts of the crew was a mystery.

Despite the devastating loss to Truro of seven vessels and 57 men and boys during the 1841 October gale, the town and its fleet had bounced back, enjoying success on the fishing grounds in the years following. The Commerce, commanded by the respected Solomon Hopkins Lombard, was well known along the coast and had shared in Truro’s success.

But just a year before the mystifying disappearance of the crew, the Commerce had had a tense encounter. Suspected of violating a treaty between the U.S. and Great Britain, the vessel had been seized and the crew detained at Port Hood, Cape Breton, by Her Majesty’s Revenue Cutter Sisters. When it was learned that the Commerce had entered the harbor in distress, having lost her dory and a sail, the Halifax authorities released the vessel and the crew. After three weeks in custody she sailed from Arichat, Cape Breton, to Truro.

On that Sunday morning in 1844 — one of those lovely days when the sea takes on that deeper tint of blue and the goldenrod glows with its deep tint of yellow — the crew of 10 had included Captain Lombard, age 29, and his brother James, 25; father and son Solomon P. Rich, 36, and Charles W. Rich, 12; Elisha Rich, 16; John L. Rich, 13; Thomas Mayo, 23, and the brother-in-law of Solomon Lombard; Reuben Pierce, the eldest of the crew at 39 and the father of seven children; Ezra Turner, 20; and Sewell Worcester, age 30. Eight of the crew had been born in Truro, one in Provincetown (Turner), and one, Worcester, in Boston, though he was living in Wellfleet and in 1839 had married a Wellfleet girl, Pamela Atwood. Four other crew members were also married. The adult crewmen were all members of the Methodist Episcopal Church in South Truro.

Several newspapers carried stories of the mystery, titling their dispatches “Another Melancholy Loss of Life of Truro Fishermen,” “The Lost Crew,” and “The Late Disaster at Truro.” Within days of the distressing discovery aboard the Commerce, the schooner’s longboat, with a plank amiss, was found along the shore in Brewster. Had the longboat sprung a leak and been swamped, drowning all aboard?

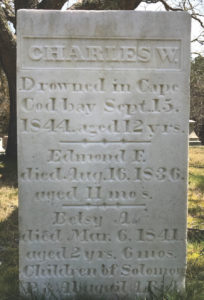

The deaths were entered in the Truro town records by Registrar Barnabas Paine, the date as Sept. 15, and the place of interment as Cape Cod Bay. In recounting the tragedy in his Truro — Cape Cod, historian Shebnah Rich wrote that over the next three weeks the bodies of the 10 crewmen were recovered over a stretch of 30 miles, and that all received the sacred rites of a home burial. Seven were buried in Pine Grove Cemetery.

Time has taken its toll on several of the headstones. That of Capt. Solomon H. Lombard lies in pieces, as does that of his brother, James H. Lombard, which rests against the headstone of the Rev. Benjamin Keith and his wife, Deliverance Atwood, in what is shown on the cemetery plan as the Parish Lot adjacent to the center driveway. As a circuit minister, the Vermont-born Rev. Keith (1788-1834) was instrumental in the organization of Methodism in Truro and was settled as pastor in 1831. In 1840, his daughter Amanda Keith married James H. Lombard. If the light reflecting off the Lombard headstone is just right, the inscription of Lombard’s drowning in Cape Cod Bay is discernible.

The headstones for Solomon P. Rich and his son Charles are yet another poignant reminder that death at sea reached deep into neighborhoods and families and across generations.

Shebnah Rich wrote, “How a crew of ten active men, many, if not all, expert swimmers, could all be drowned in smooth water, so near the shore, probably having the usual complement of oars, thwarts, etc. — how the leak occurred, and why it could not have been stopped, with many other queries, will ever remain a mystery.”

The town of Truro makes plans of its cemeteries available on the cemetery commission page of its website, truro-ma.gov. For the curious, Leo Damore’s In His Garden recounts the events of 1969.