In Tessera C. Knowles’s painting Saltine at Egg’s Isle, Provincetown’s drag mistress of political satire sits in a chair on the sand behind the Julie Heller Gallery surrounded by an imaginary beachfront garden made of tiny circles, squiggles, and jots. It’s a sort of pointillist landscape of olive beach grasses, shards of blue sea glass, and the bits of things that make up the wrack line, with the harbor and sky behind.

The painting reveals Knowles’s way of seeing this place and its nature in colorful, whimsical detail — a talent she is now using to transform the landscapes of Provincetown with a delicate blend of art and horticultural know-how as a garden designer.

Knowles arrived on a whim in 2013 — a college friend persuaded her to share a bed in Harry Kemp’s shack on Tasha Hill for a summer after they graduated from the University of Vermont. After that summer, Knowles traveled to Germany and Iceland before returning to the U.S. for a job in social work. She says she burned out quickly.

“I left that job with the romantic idea that I would visit my friends in Provincetown for a couple of weeks and then go on a solo road trip to the Southwest and be an artist in Santa Fe,” Knowles says.

But Provincetown had other plans for her, and she never made it to Santa Fe. The landscape drew her in. “I’d never felt more connected to a place than I felt in the National Seashore,” she says. She enrolled in a natural science illustration class at the Center for Coastal Studies and developed her painting practice, trying out a few different day jobs: if you’re a coffee drinker, she might have made you a cortado at Kohi; you might have noticed her byline in these pages.

It wasn’t until she started working with landscaper Gunter Leirer that she really felt rooted. “It was the first job I ever had that I enjoyed and that didn’t exhaust me or leave me emotionally drained,” she says.

Her interest in landscaping was fertilized two years ago with a new opportunity to work with the landscape designer Sam Spiegel. He had seen her detailed hand-drawn illustrations of carrots on a tote bag and wondered if she might make perspective drawings for his clients. Knowles had already started taking garden design classes, and the collaboration came easily.

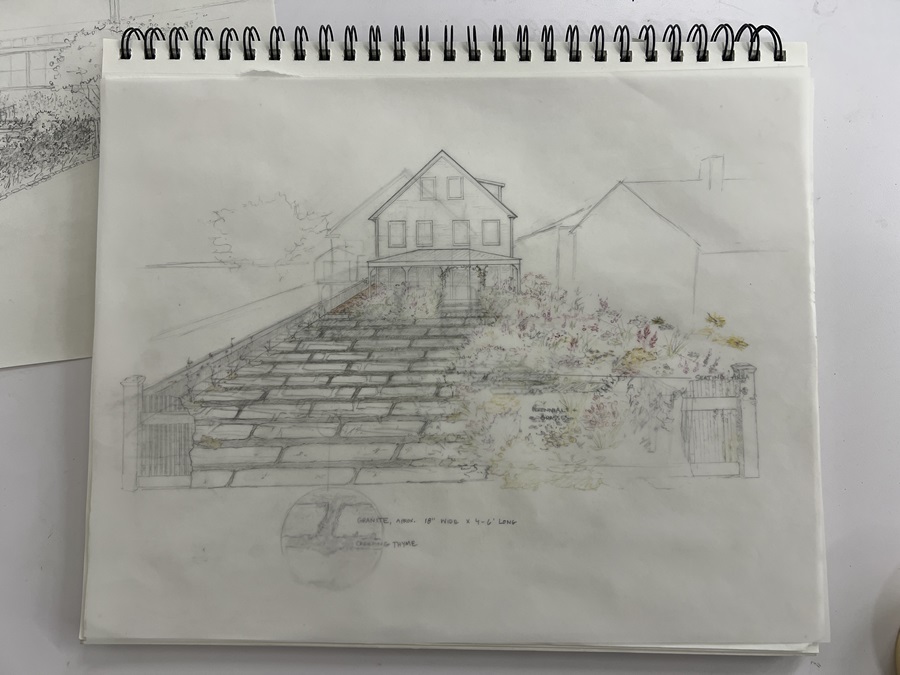

They would meet with clients together and discuss ideas about plants and aesthetics, with Knowles giving the vision shape on a sketchpad afterwards.

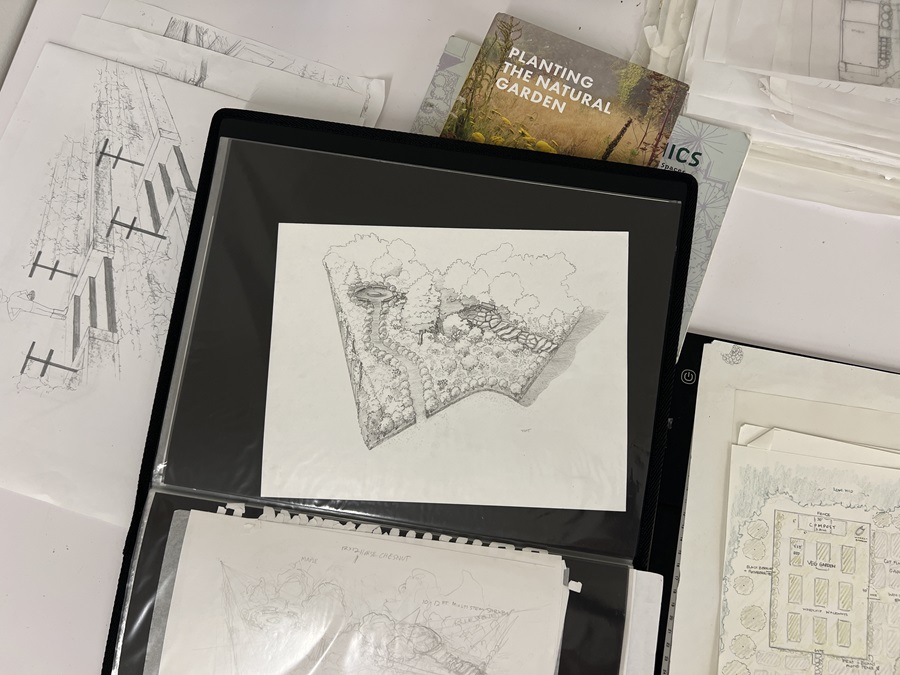

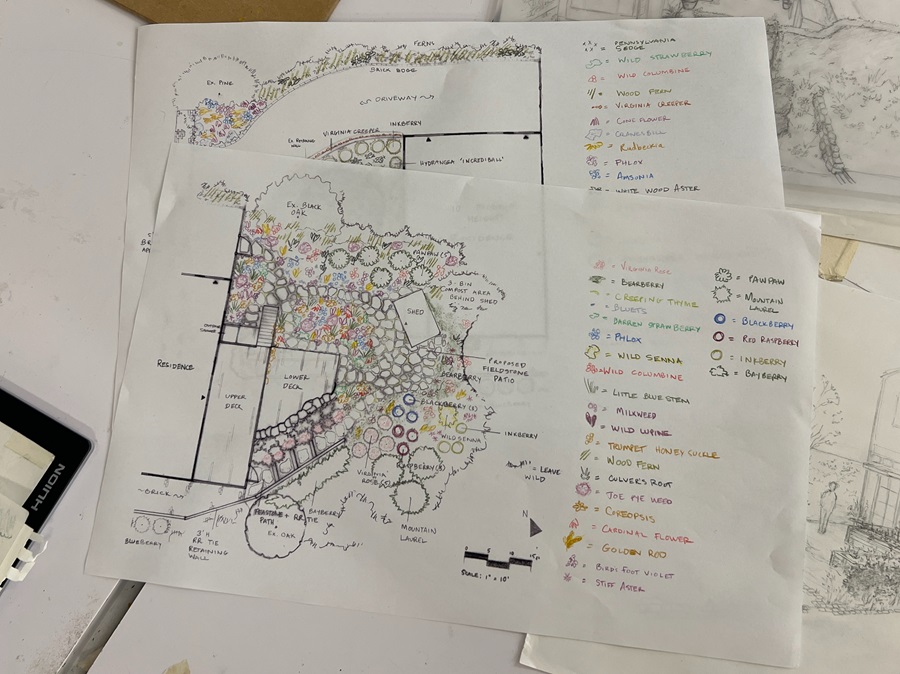

Knowles always starts a sketch by hand, using graphite and colored pencils and then goes into Photoshop “to clean things up a bit” before presenting a design to a client. Most times the drawing is accompanied by a list of potential plants to incorporate based on a combination of her knowledge and intuition and the client’s preferences. She keeps drawers and folders full of draft sketches and notebooks documenting past designs in her studio at the Provincetown Commons.

“In my ideal world, each garden I design would be like a painting,” Knowles says. “But the reality is that clients sometimes have different ideas than I do.” Arriving at a design is like editing a canvas but with both designer and client bringing their views to the table.

“You think about Provincetown gardens from a historical perspective,” says Spiegel, “and it’s mostly cottage gardens and English gardens. Tess melds the old style with the New Perennial movement” inspired by Dutch garden designer Piet Oudolf, whose approach is more naturalistic and structural than decorative.

That means she combines the aesthetics of English gardens — trellises, stone paths, and swaths of roses — with Cape Cod native species like goldenrod, bayberry, and wild lupines. She hates lawns.

Knowles took over Spiegel’s business in February and renamed it Meristem Designs. “I think she really gets the relationship between nature and art and gardens,” Spiegel says. “That’s rare in this field.”

Considering this new chapter, Knowles is quick to point out what she’s learned both from Spiegel and Leirer, two bosses who became friends and mentors, and from the broader community of landscapers on the Outer Cape including arborist Eugene Khukau and plantsman Tim Callis, who designed many of the gardens she worked in with Leirer.

Knowles says that in every garden she works on, she tries to plant an invitation to slow down and look closer. In this idea there is something of the essence of Knowles herself. She admits to a predilection for small things.

“When I’m in nature, walking and exploring and crouching down with my camera, I feel like I get into this meditative state,” she says. “I get to empathize with the little things that get overlooked.

“I’m the person who will join to watch a sunset, but I’ll likely end up squatting on the ground looking at the tiniest little broken seashell instead,” she says.

She likes volunteers, like violets, “that grow between stones or in the driveway,” she says. “Happy accidents,” she calls them. “I think that’s something I’ve really tried to also embrace in my life and artistic practice.”

She and Spiegel visited Great Dixter last year during a trip to the U.K. for the Chelsea Garden Show. It’s the place where the late Christopher Lloyd expanded his family’s fabled and, Knowles says, “funky, whimsical, and huge” garden. “It’s my absolute dream to create gardens that borrow little pieces of that,” she says. “There is so much color, yet certain weeds are allowed to grow.”