Stare into Susan Bee’s Eye of the Storm, a painting prominently displayed at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, and you’ll observe bundles of tightly knit red, white, and blue waves ascending into an earth-toned whirlpool; the short end of a yellow triangle points to a watchful eye, staring back. The triangle reveals itself as a large sail. A small orange figure, the painter, sits in the untethered boat. We don’t know if the boat is moving toward the eye, or if the artist in it is a viewer, too, with us, witnessing the scene.

As a teenager summering in Provincetown with her family, Bee took sailing lessons at Flyer’s Boatyard. “I had no aptitude for sailing, really,” she says. “But I always like seeing the sailboats in Provincetown. For me, boats on the harbor symbolize a place to get away,” the artist says, decades after those lessons.

“Eye of the Storm” is also the title of Susan Bee’s solo show at PAAM now through Nov. 17. In it, single-masted sailboats occupied by a lone figure are one of Bee’s recurrent images. Bee’s PAAM show opened on a sparkling late summer afternoon with white sailboats dotting Provincetown Harbor.

Bee painted Eye of the Storm the year her father died, she says, and it is based on a dream. While sea imagery and sailing link Bee and her family to Provincetown, the watchful eye is connected to the kabbalah, a mystical part of Jewish tradition that contemplates the essence of divinity.

“The eye also symbolizes the relationship between artist and viewer,” Bee says. Scenes of calm and turbulence and of the viewer and the viewed recur in Bee’s work.

Late Echo shows a woman sitting calmly on a rocky shore viewing sailboats drifting by. The title, Bee says, was suggested by a John Ashbery poem asking whether there is anything left to write about. Bee’s diverse 40-year body of work on view — for this show she and her curator, poet Johanna Drucker, selected paintings made between 1981 and 2023 — offers an affirmative response. At least, there are indeed things left to paint.

Petunia Pig flaunts a fat paintbrush while giving the side-eye to a seated model in the prominently situated Portrait of the Artist as a Young Pig. In it, Bee is both viewer and viewed. “I am the woman in the nude self-portrait, being scolded by Petunia Pig and urged to paint,” she says. “It is both satirical and personal.”

Bee’s parents, Miriam and Sigmund Laufer, were artists. They lived in Manhattan and began spending summers in Provincetown in the mid-1950s, vacationing while creating and exhibiting artwork. These seasonal rituals were shared with artist friends Chaim and Renee Gross (Gross’s six-foot bronze sculpture Tourists stands in front of the Provincetown Public Library) and Ilya and Resia Schor.

A curious child who started making art at a young age, Bee took drawing classes at PAAM during those visits and painted with printmaker Seong Moy in his studio on Miller Hill Road.

She also tagged along to Provincetown’s openings and parties where questions like “What is art?” dominated adult conversation. Some of the painters were realists, like her father, who showed etchings and color prints in a Madison Avenue gallery, while others, including Bee’s mother, painted more like an abstract expressionist, from a challenging, feminist point of view.

“My mother’s artwork could be fierce,” Bee says. “She could be very in-your-face and had a lot to say.”

Bee remains close to her childhood friends, artists Mimi Gross and Mira Schor. For two decades Bee and Schor collaborated on M/E/A/N/I/N/G, a journal of reviews, opinion pieces, poetry, and artwork. A selection from it was published in 2000 by Duke University Press.

In the 1970s, while earning a master’s degree in art history and art at Hunter College, Bee was making abstract photograms and writing about European surrealists Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy. But in 1980, when her mother died of a stroke at age 60, she returned to painting.

“My photographs were already getting painterly,” she says. “But I went back to figuration and oil painting. It was an emotional choice.”

To the Lighthouse I, which she painted in 1981, is named after the Virginia Woolf novel. Bee notes that the novel is “about the death of the family matriarch and features a woman painter having a vision.” It is also a defense of subjectivity in art. While this particular lighthouse is in Nova Scotia, where Bee spent time after her mother’s death, the loosely scattered houses, puffy clouds, and bluebird sky suggest the Outer Cape’s indelible charms.

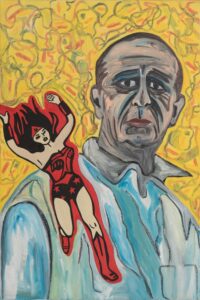

A couple of years later, Bee painted Marsden Hartley Meets Wonder Woman, a sendup of one of her favorite painters. “In my continuing quest for feminist heroines, I featured him,” she says about Hartley, a painter and poet who was in town in 1916. In Bee’s painting, Hartley is “targeted by this bright red superwoman” swooping down over the bewildered painter’s shoulder. “How do you paint what you’re thinking about,” Bee asks, “without being too explicit?”

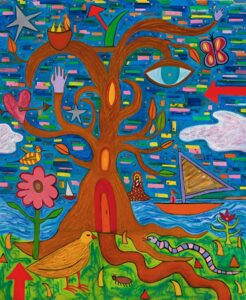

Bee’s mother continues to be a presence in her emotional and creative life. In 2006, Manhattan’s A.I.R. Gallery, an artist-run nonprofit exhibition space where Bee had been showing for more than two decades, exhibited Seeing Double: Paintings by Susan Bee and Miriam Laufer. Bee showed paintings from Philosophical Trees, a series she has continued and which includes Treehouse, a 2022 painting that is in the current PAAM show.

In 2016, PAAM exhibited Views and Vignettes, the Works of Miriam Laufer. “Laufer’s engagement with autobiographical subject matter and frank depiction of the female body,” says curator Drucker, “is unusual for a woman painter of her generation.”

Bee’s Ahava Berlin has a haunting backstory. She painted it in 2012, inspired by a trip she made to Berlin’s Jewish quarter to see the school where her mother lived as a child. Bee’s painting was based on a photo of her outside the war-scarred, graffiti-marred building taken by her husband, the poet Charles Bernstein. Standing close to Ahava Berlin, the viewer sees splashes of red, perhaps suggesting blood — not all the children were rescued. “Ahava” is the Hebrew word for love. Her mother later emigrated to Palestine, where she continued to study art.

Bee and Bernstein met when both were in high school in Manhattan. They continue to support each other’s creative trajectories, which include collaborating with poets. The PAAM exhibit includes two handmade books Bee made with her husband. For Little Orphan Anagram, Bee selected Bernstein’s poems, hand-coloring each page.

“I love the poets,” she says with a smile. “And they are my best audience. They also buy a lot of my work.”

Bee’s Windswept is a one-of-a-kind hand-painted accordion-style book, done in Provincetown during the first summer of the pandemic. Bee calls it “a meditation on the bay and water and sun and lost time.” Its pages are dotted with Bee’s signature metaphors: a sailboat with its lone passenger, a lighthouse, the bright sun.

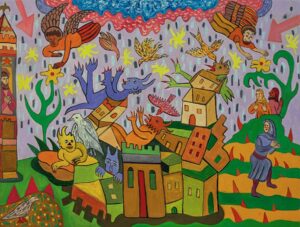

In this show, the painter takes the viewer without apology from such summer idylls straight into the phantasmagoric and even terrifying. Days of Awe, part of Bee’s “Apocalypse” series, is based on a French apocalypse tapestry from the 1400s. It reveals the concerns about perception and the brevity of life that animate Bee, right alongside the impish humor she continues to invest in her shifting cosmos of characters.

“I like the way it conjures up a whole medieval array of devils, demons, saints, and mythic creatures in a fantastic landscape,” she says.

Symbols and Metaphors

The event: Susan Bee discusses her work in the show “Eye of the Storm”

The time: Thursday, Sept. 12, 6 p.m.

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: $15 museum admission; free for members; the show is on view through Nov. 17