Whether you’re an early riser, twilight stroller, nighttime stargazer, Moon lover, planet fan, or meteor enthusiast, there’s something for you in the night sky this summer. Here’s a suggested itinerary, starting with the Summer Triangle, our constant summer companion.

The Summer Triangle is an asterism (a pattern of stars that isn’t an official constellation) that’s easy to see after dark from June through August. (You’re probably familiar with another asterism, the Big Dipper, which is part of the much larger constellation Ursa Major, the Big Bear.)

Step outside on any night in summer, face east, and look up. The prominent star almost directly overhead is Vega. Direct your gaze a short distance to your right and a little down and you’ll strike another bright star. That’s Altair. Finally, look for a slightly dimmer star to the left of Altair and below Vega. That’s Deneb. Imagine lines connecting all three stars and you’ve got the Summer Triangle.

Next, try identifying the three different constellations that each star is part of. A star map can help — there are printed and app versions. Deneb resides in Cygnus, the swan, an easy constellation to make out and a favorite of mine partly for the black hole that lurks there. Vega is part of Lyra, the lyre, a stringed instrument of ancient Greece. Altair’s home constellation is Aquila, the eagle. The name Altair comes to us from ancient Arab astronomers, who called this constellation al-nasr al-tair, the flying eagle.

Our next celestial sight is very date-specific. At dusk on Aug. 5 there will be a lovely close pairing of the crescent Moon and the bright planet Venus. Look west just after dark. The Moon will be a beautiful slender crescent; the brilliant blue-white star that’s almost close enough to touch it is Venus.

Things get more challenging with the annual Perseid meteor shower, which peaks in the early morning hours before dawn on Aug. 12. Every year in August, Earth plows through the debris trail of Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which consists of specks of ice and small rocks ranging in size from grains of sand to pebbles. As we collide with these fragments at over 132,000 miles per hour, the heat generated by friction in the upper atmosphere vaporizes them; we call the resulting fiery streaks of incandescent gas shooting stars or, more properly, meteors.

From our perspective on the ground, this debris trail lies across the constellation Perseus. If you trace the path of Perseid meteors, you’ll find they all originate in the constellation Perseus, for which they are named.

You can see meteors every minute or two on any night of the year. But these are known as sporadics: random space debris not associated with any comet and appearing from all directions. They’re also not usually as bright or long-trailed as a Perseid. In good years (and 2024 could be a good year) observers under fairly dark skies like the ones we have on the Outer Cape might see 50 to 100 bright, long-trailed Perseid meteors per hour during the peak.

Here’s the hard part: set your alarm for 4 a.m. on Aug. 12 and head outside while it’s still dark. Any clear patch of sky will do. Just get comfortable and keep your eyes on the sky.

Finally, as summer wanes, a beautiful sight awaits the strong-willed early riser. An hour before sunrise on Aug. 27 the Moon and the planets Jupiter and Mars will draw close together high in the southeast. The Moon is easy to spot. Jupiter is the bright gold-white star. Mars is, of course, the red star. The three will form a neat triangle. If the weather is bad that morning, they will still be fairly close on the next day at the same early hour.

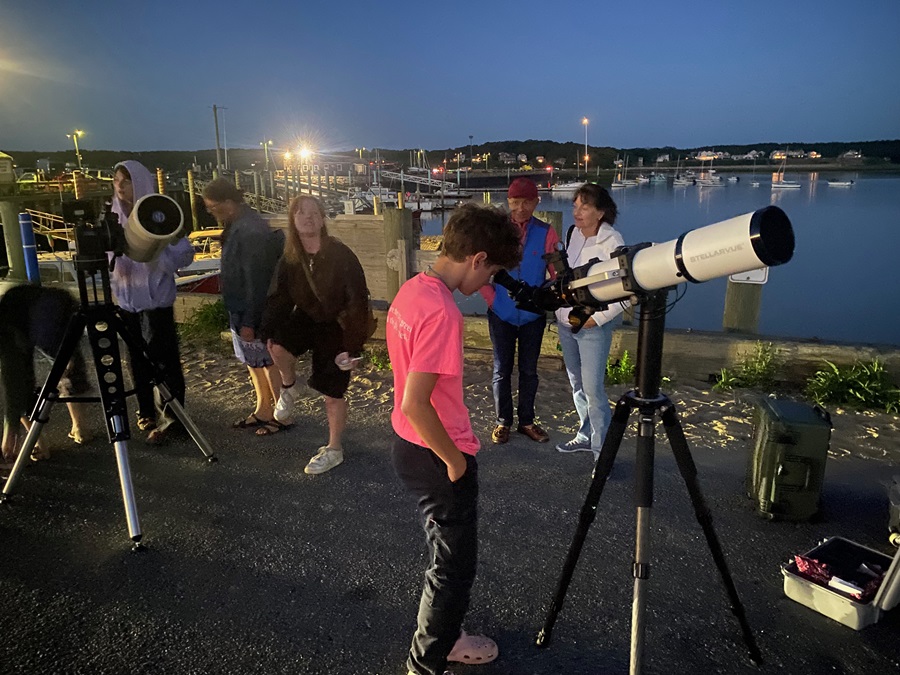

I hope you’re able to see one of these celestial events this summer, and maybe I’ll see you some evening at the beach. Clear skies!