Usually, Studio Lacombe, located in the Whalers Wharf at 237 Commercial St. in Provincetown, exhibits the work of Gaston Lacombe. But opening Friday, Aug. 6 and running through Aug. 16 is “Landscapes,” a show of paintings by Benji Weinryb Grohsgal. The 20 small acrylics in the show are semi-abstractions of lollipop trees and quasi-figurative forms. The colors are flat and punchy, the shapes lumpy and long — a graphic dream world of ambiguity and longing. “Through this work, Benji is trying to preserve his own moments of joy in the face of entropy,” says the gallery announcement. “In his mind, these are the last clumps of matter and memory as we approach the heat death of the universe.” There will be a reception on Friday, Aug. 6, from 7 to 9 p.m. The gallery is open Thursday through Monday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Studio Lacombe

MIXED MEDIA

Gaston Lacombe Comes Full Circle

His Words of Power series moves past photography

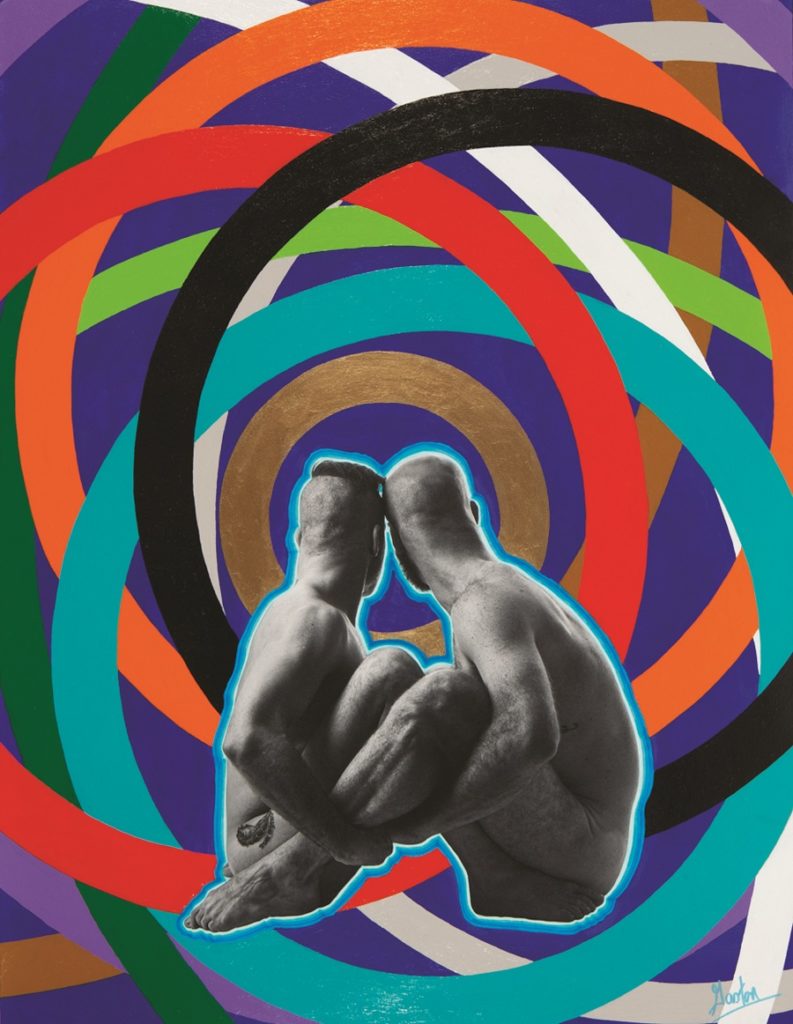

Walking into Gaston Lacombe’s studio in Whaler’s Wharf feels like stepping into a rainbow. Brightly colored works hang on every wall, competing for attention. Many juxtapose black-and-white photography with incandescent backgrounds — mixed-media celebrations of the male nude and queer experience.

The largest wall in Lacombe’s space, however, shows a bold interplay of circles and seemingly random abstract patterns. A closer look reveals hidden letters spelling out what Lacombe calls “words of power.” This new series of the same title will be featured at Studio Lacombe through June.

The inspiration for Words of Power came when Lacombe was asked to participate in a fundraiser of artwork that included the word “hope.”

“At first, I replied, ‘I don’t do words!’ ” Lacombe says, “but I had a vision and decided to go with it.” Before the auction, he hung the piece in his studio window. Dozens of passersby stopped each day to look.

He decided to start a series depicting words with a personal meaning “beyond the dictionary.”

“I abstract the letters into the piece, so the word is not obvious,” he says. “I want viewers to spend time with the work, reflect on the word and wonder: ‘Why is that word on the wall?’ ”

Words of Power represents a bold step into an artistic style Lacombe has been covertly drawn to since childhood. “I have been so deeply associated with photography that people come in here and expect it,” says Lacombe, “but from a very young age I didn’t want to reproduce reality. I have drawings from when I was five, six, seven years old that are all abstract. I would work on a single piece for days, finding such liberation in letting shapes flow as they came out of my brain.”

The adults in Lacombe’s life didn’t encourage his art, so he took the more conventional path of studying history and political science. It allowed him to move to Ontario, finally stepping away from the small, conservative town in New Brunswick, Canada where he grew up.

His history studies inspired him, in 1992, to move to Latvia, where he spent 16 years. “That was a strange detour in my life,” he says, “and it had a lot to do with the fact that Latvia as a nation has an extremely vibrant cultural identity. When they finally broke from the Soviet Union in 1992, the Latvian people were free at last to express themselves.” And so was Lacombe, not yet as an artist, but as a gay man. “At that time, Latvia was very open to anything. I came out when I was there, and nobody cared about the fact that I was gay — it was a new world.”

The post-Communist openness did not last. Lacombe and his then-husband received death threats and eventually fled to the U.S. Unable to work because he was not yet a citizen, Lacombe went back to school to study photography. “I had a camera since I was a small child,” he says. “Photography wasn’t something I was deeply passionate about, but it was a step toward art.”

He became a photojournalist for National Geographic, the Smithsonian, and the World Wildlife Fund. But by 2015, he felt the need to “be myself again, to actually learn who I am.” He left his successful career and his husband and moved to Provincetown to create art.

Photographing male nudes prompted the “unraveling of my identity, of my orientation, of who I am,” Lacombe says. “I grew up in a very conservative Christian environment where the act of just looking was very strongly condemned. Working with models, I was giving myself the permission to look, not necessarily lasciviously, but just to explore bodies, because for 40-some years I had willingly or subconsciously completely shut that out of my life.”

Then, in January 2020, Lacombe showed fellow Provincetown artist Pete Hocking an abstract piece he had created for himself. “Pete asked me why I don’t do more of this kind of work, and I replied that these were just some silly lines and circles I’d been doing since I was a child,” Lacombe says. “He told me to run with it, that it would eventually mean something. He unlocked that part of me.”

During the pandemic, because working with models in his studio was not safe, Lacombe focused on these new, introspective paintings. “The pandemic gave us a lot of time to experiment, and it forced me to develop a unique voice,” he says. “While photography was about viewing another, I am very conscious that every piece I’m doing now is literally putting a part of myself on the wall.”

Lacombe is now working on a newer series combining metallic paint pen with nude photographs. The result evokes halos and Christian icons. “I’ve experimented with every type of art I can think of,” he says. “Photography was one of these on my trajectory, but not the only one. My new work is not a deviation — it’s all part of a natural progression.

“There’s this great word in Latvian,” Lacombe says, “which doesn’t exist in English, but it translates to ‘all-permissiveness.’ I love this concept of there being no boundaries imposed by society. You can explore who you want to be, and that’s what Provincetown is to me.”