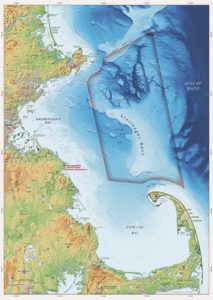

PROVINCETOWN — The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, which manages the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (SBNMS) — an 842-square-mile stretch of ocean three miles north of Provincetown — has drafted an extensive game plan for the next 10 years.

Since the last management plan was issued in 2010, “we’ve had advances in science and changes in environmental issues,” said Anne Smrcina, the education and outreach coordinator at the SBNMS.

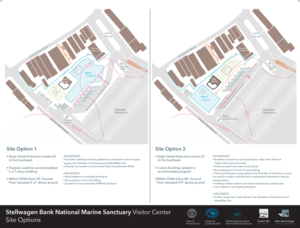

The new plan outlines 15 areas for action, including the development of a visitor center proposed for MacMillan Pier. “Provincetown is a key gateway to the offshore sanctuary,” said Pete DeCola, SBNMS’s superintendent. “Most of the whale watching trips head out from there, and we’re mindful of what the sanctuary can do to promote a healthy environment and a strong ‘blue economy.’ ”

SBNMS has invited public comment on the plan through Jan. 21. Smrcina said the sanctuary is hoping to hear from fishermen, biologists, U.S. Coast Guard members, and other stakeholders.

Other key areas include action on climate change, whale conservation, and shipwrecks. Climate change became a more urgent focus of sanctuary research after a 2015 study found that “sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Maine increased faster than 99 percent of the global ocean.”

The plan touches on familiar obstacles to whale conservation, like entanglements in fishing gear and ship strikes, but it also takes on a newly recognized threat: noise. In particular, the plan proposes to look at how humpbacks and North Atlantic right whales fare in the sanctuary’s noisy underwater environment.

Historic shipwrecks got their own section, too, since nearby scallop beds are set to reopen in April 2022. A concern is the possible effect of dredges and bottom trawls, which may very well chug right into those sunken schooners.

The Whales’ Soundscape

Large domestic and foreign-flagged vessels crisscross the waters of Stellwagen Bank, following designated shipping lanes to and from the Port of Boston. Tankers ferrying liquefied natural gas and oil also join the mix, along with barges, cruise liners, and container ships. Amid all this traffic, whales in the sanctuary are at risk of fatal ship strikes.

Over the past 10 years, NOAA has been trying to keep vessel operators abreast of nearby humpbacks and right whales. They’ve rolled out WhaleAlert, an app that offers the operators maps of whale management areas, recommended routes, and real-time warnings. The Right Whale Corporate Responsibility program also kicked off in 2010, recognizing top shipping companies who slow down to comply with speed regulations in management areas. And SBNMS has been promoting gear modifications to prevent entanglements.

SBNMS’s draft plan aims to tackle how noise disturbances degrade the sanctuary’s “acoustic habitat” and how that affects whales and other soniferous species — animals that depend on sound for communication, mating, and spawning, among others behaviors.

A NOAA and National Park Service study that began in 2016 compared sound levels in Stellwagen Bank and three other national sanctuaries: Gray’s Reef off Georgia, the Florida Keys, and Flower Garden Banks in the Gulf of Mexico. It found that Stellwagen Bank had the highest sound levels of the four.

Scallops and Shipwrecks

Ship strikes threaten not only humpbacks and right whales but also wrecked coal schooners, like the Palmer and the Crary.

In 1902, the Frank A. Palmer and the Louise B. Crary, each loaded with 3,000 tons of coal, departed from Newport News, Va. But as they neared Boston, they encountered a five-day nor’easter. The Crary rammed into the Palmer, and both ships sank to a depth of more than 300 feet, where they have lain for more than a century.

Stellwagen Bank is home to 47 shipwrecks — seven of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places (both the Palmer and Crary made the list). “There could be more out there,” DeCola said. “We just haven’t found them yet.”

SBNMS’s management plan identifies these wrecks as “time capsules” of the region’s maritime heritage. But an “emerging issue” looms for this cultural resource, according to DeCola. Modern-day scallop dredges and bottom trawls could kick these sunken ships while they’re already hundreds of feet down.

About four years ago, scallops bloomed on Stellwagen Bank, and soon a derby-style commercial fishery converged on the area, surprising the sanctuary’s ecologists. “It hadn’t been on our radar,” said Alice Stratton, a sanctuary marine ecologist and permit coordinator, who helped put together the plan.

“People were getting out and catching as many scallops as they could,” DeCola added. “That ended up being a free-for-all.”

Dredges dragged the bottom, raking up shellfish and also skimming close to the ships. “If a scallop dredge makes contact with a shipwreck, well, the shipwreck is going to lose about every time,” DeCola said.

The Stellwagen Bank scallop fishery has since cooled, after shellfish surveys detected a plunge in harvestable-size stock. After the initial bonanza, the New England Fishery Management Council closed the area from 2020 to 2021, to allow time for smaller scallops to grow.

That hiatus also allowed the sanctuary to develop a shipwreck avoidance program, which aims to notify fishing captains of the locations of wrecks relative to the scallop beds. SBNMS has also worked with groundfish sector managers such as the Greater Atlantic Regional Fisheries Office, which issues permits, to give fishermen a heads up.

This year, the pilot program will be put to the test. The Stellwagen Bank scallop beds are slated to reopen on April 1, 2022, according to a NEFMC press release.

The public comment period on the new sanctuary management plan ends Jan. 21. The plan and instructions on how to comment can be found at https://stellwagen.noaa.gov/. Comments may also be sent by email to [email protected].

Caitlin Townsend contributed reporting for this article.