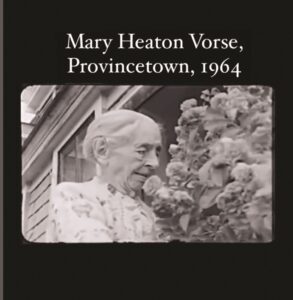

The black-and-white footage zooms in on an elderly woman, her white hair tied back and a soft smile on her face, as she prunes an explosion of flowers beside her house.

“Why do I like this scrubby, sandy country more than any other?” the woman asks, a sea breeze swirling around her. “Perhaps it’s the effect of light. There’s a peculiar light around Provincetown.”

The woman is Mary Heaton Vorse, labor journalist and author of Time and the Town: A Provincetown Chronicle, published in 1942. She was 90 in 1964 when she appeared in the fourth episode of the short-lived National Educational Television series America’s Crises.

In the clip, Vorse offers a bit of town lore appropriate for this season. “I’ve lived in this house fifty-six or -seven years,” she says. “It belonged to a whaling captain named Kibbe Cook. I have his rocking chair here and I have his logs and his writing material. His ghost walks. He does. He paces the halls. He’s a harmless ghost. We all call it ‘Kibbie Cook’ because it sounds like a captain slowly pacing his deck.”

This film clip from the past, posted on Instagram, has received almost 15,000 “likes.” It is one of 674 entries on @provincetownarcheology, an account curated by Stefan Anikewich that highlights the history of Provincetown and has more than 18,000 followers.

Anikewich, who splits his time between Provincetown and New Rochelle, N.Y., says he has been discovering the hidden history of the town since he was a child. “I’ve been a beachcomber since I was 12 years old,” he says.

Walking the shore from Race Point to Long Point, he says, he occupies himself “looking for fragments of our history: pieces of porcelain, shards of bottles that were discarded, items from the whaling industry, Indian artifacts — not taking it, just observing it.”

He started his Instagram account in the summer of 2021, posting a picture of a shard of porcelain he found on the beach. Within a few hours, he had 45 followers, and the photo had 30 likes. That’s when he realized: “Here’s my opportunity to share my passion about Provincetown.”

Anikewich’s posts appear the same way a beachcomber’s artifacts do — gems from nearly every corner and decade of the town’s history surface with a strangely pleasing refusal to submit to an orderly timeline. There’s an 1898 photo of Provincetown taken from the harbor, a 1970s photo of a woman with a soft sculpture of the Pilgrim Monument in her bike basket, 1957 footage of a stroll down Commercial Street, and a 1916 photo of students in Charles Hawthorne’s Cape Cod School of Art painting on the wharf.

The Library of Congress, David W. Dunlap’s Building Provincetown: The Provincetown Encyclopedia, and state, city, and university archives are sources Anikewich turns to for material. He spends “hours upon hours sifting through archives, looking at pictures, and reading their descriptions,” he says, then cross-referencing the information to correct errors so that each posting is accurate.

Anikewich also taps his personal collection of memorabilia for ideas. It used to consist of things acquired at auctions and estate sales. These days he also gets messages from people in the community who want to send him things. He’s glad people want to support what he’s doing because, for him, the account is not just for entertainment, it’s a necessary tool in the fight for preservation of Provincetown’s past. Learning the town’s history, Anikewich says, “awakens the mind, the imagination to how important this place is.”

The past mingles with the present at times in Anikewich’s Instagram posts, as does fact with opinion. He has advocated for local families in their ongoing fight with the Cape Cod National Seashore over changes in the dune shack leases. “To just uproot these people and replace them with strangers who have no concept of how to take care of these lands is absolutely ruthless,” he says. “We have to protect these families because they protect our lands.”

His posts convey his worries about the future, too, with some highlighting the displacement of families because of the soaring price of real estate in town and the need for affordable housing solutions. He says sharing the history of Provincetown’s past and activism for its present go hand in hand.

Anikewich’s place is near the land on Nelson Avenue that the town has been considering purchasing for the creation of affordable housing. He’s all for it. “We can’t say, ‘Oh, it’s in my back yard; this is a problem.’ No, we have to say, ‘It’s in my back yard, and I’m doing what I can do to save Provincetown.’ ”

Every day, Anikewich receives messages from people saying his account brings back memories of lost loved ones and of joyous days and years spent here. “We have to get back to more of that,” he says, “appreciating this place.” The way he sees it, “We’ve been a beacon for people for a long time.”