Picture yourself taking an unhurried walk through a wildflower garden with a small child. You slow down as the child examines the curve of a leaf, the shape of a blossom, and you crouch down as she observes the peculiar dance of a tiny, shiny bug. This is the kind of measured vision that Nancy Ekholm Burkert brings to her children’s book illustrations.

Burkert, who lived in Wisconsin before moving to Orleans in 1998, received the 2019 Society of Illustrators Lifetime Achievement Award, an honor shared by such luminaries of children’s literature as Maurice Sendak, Theodore Geisel, Eric Carle, Chris Van Allsburg, and Tomie dePaola. At a time when many Outer Cape parents are at home, educating and entertaining their kids, the Independent decided to catch up with Burkert, a major figure in our midst.

Best known, perhaps, for her pen and ink illustrations for Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach, published in 1961, Burkert spent as much as a decade on each of her meticulously researched and intricately drawn projects, which often celebrate uniqueness in nature.

“There are no two leaves alike in the world,” she says. “One of my goals was always specificity of form. I think of it as a way to help children identify the variety in nature, and in doing so, also to grow their interest in preserving the natural world around us.”

Burkert believes in never dumbing down to young readers — and quotes the English illustrator Arthur Rackham, whom she admires: “Nothing but the best is good enough for children.” And for others, too: Burkert’s books, like all great children’s literature, offer as much or more to the adults who read them aloud.

Burkert’s illustrations, most of which were done in colored inks and watercolor, often include the hidden likenesses of notable figures and people she knows. Her illustrations in James and the Giant Peach, for example, include the faces of author Roald Dahl as well as publisher Alfred Knopf.

Burkert’s daughter, Claire, was the model for Snow White in her illustrations for Snow-White and the Seven Dwarfs: A Tale From the Brothers Grimm, a Caldecott Medal winner in 1973, for which Burkert traveled to Germany to study the flora of the Black Forest.

“I often put family members and friends in my books,” Burkert says. “In a way, I was making up for the time I couldn’t spend with my children when I was working. So, they were there, with me, present in my books.”

Burkert’s son, Rand, a musician, children’s book author, and passionate organic gardener, who now shares the family’s Orleans home — Samuel Sparrow’s 1820 farmhouse — with his mother, grew up recognizing himself in her illustrations. “I was born just as my mom was finishing the last pictures for James, so I appear as a squalling baby in the parade when the peach is going by on a Mack truck,” Rand says with a laugh.

Rand was also his mother’s inspiration for the main characters of 1989’s Valentine & Orson, Burkert’s favorite of her own books. In this medieval tale, the text of which Burkert herself adapted into the form of a verse play, a pair of twin brothers are separated at birth. One is raised as a prince, the other as a wildling. When they meet by accident, they fight almost to the death.

“I saw a print by Bruegel that shows the wild man, so I looked up the story and was led to this text,” Burkert says. “I am a Quaker and, as such, deeply committed to peace and peace activities. The thing that struck me, and the whole reason I did this book, was the rapprochement between the two brothers. They’re going to kill one another, but then they have this sense of their common humanity and they stop.”

In the images of himself as a young man in Valentine & Orson, Rand says his mother saw aspects of him that he had not yet discovered: “She recognized something about me that is maybe true of everybody: that we have a civilized side and we have a wild side. And they need each other.”

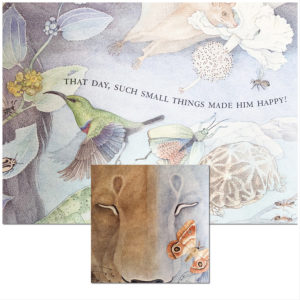

Burkert’s most recent illustration project was Mouse & Lion in 2011, an adaptation by Rand of the Aesop fable. (Since then, Burkert devoted herself to caring for her husband, the artist Bob Burkert, who died last year.) This ancient story underscores another timely message about humanity, Rand says: “The lion, who represents the powerful, gradually recognizes that he is indebted to a smaller, weaker creature — someone he initially humiliates. We want our leaders to be worthy of us: to be calm and wise, and to be humble and listen. This tale embodies that.”

Mouse & Lion was a stylistic departure for Burkert — her art continues to evolve.

“In the beginning of my entry into the field,” she says, “the American picture book was all about the flow of the words with the images. They intermingled. Children’s books were judged by how well the words and images worked together. Having come from a fine art background and training, I felt that the words interfered with the integrity of the space for the art, so in many of my books, the images are separate from the words. Mouse & Lion was the first book where I let them flow more or less together.” She adds, “I’m really happy with how it worked out.”