TRURO — Like many men of his generation, my father was not much of a cook. He was good with burgers and steaks and made a fine tuna salad. But when it came to smoking bluefish, he worked magic.

His recipe went something like this:

Catch a bluefish at a Truro beach, preferably during a blitz, and filet it on the deck of the house, washing away the blood and guts with a garden hose. Prep the filets with some mysterious ingredients and crank up the smoker. Let the fish smoke for hours — long enough to take a shower and have a nap on the living room couch, and for the tide to come in and fill the Pamet marsh like a lake.

The result was uniquely his — not too smoky, not too fishy, and nothing like the dark, hard, salty smoked bluefish you could buy in the market. Pale, moist, and with a delicate brininess, his version was even better than the pricey kippered salmon we ate with cream cheese on bagels back home in New York. Feasting on the smoked bluefish before dinner was a summer ritual when I was a kid, and long after I’d grown up. We all loved it, from the youngest grandchild on up.

With a breeze off the bay coming through the screen door, Dad would sit in his favorite chair, his legs on the ottoman, a tumbler of Glenmorangie in one hand and the jaunty clarinet of Benny Goodman on the radio.

“Who’s going to make me a cracker?” he’d say, and a grandson would jump to slather a cracker with cream cheese and spread some of the soft fish on top.

Dad grew up poor. One summer, his father ran a burger joint in a beach town in Connecticut. Dad spent long hot days at the grill with his mother, flipping burgers for the teenagers relaxing at the shore. For my father, who put himself through college and law school, summers were for working. Beach houses and lazy days spent fishing were for rich kids.

Dad was proud of his success, for traveling far enough in life to have a summer house on Cape Cod. But I don’t think he ever relished the satisfaction of being a good provider as much as he did when we devoured the fish that he caught and smoked himself.

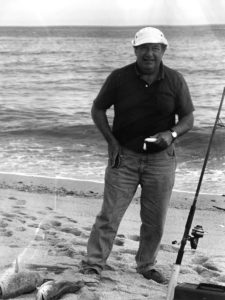

But then my father got sick. He had trouble breathing, so the smoker stayed in the shed. His time at the beach was limited to the occasional drive in his old Jeep Cherokee, portable oxygen tank in tow, to look at the water.

The summer Dad died, I didn’t have much appetite for anything. That was five years ago. A friend promised that, in time, I’d be able to remember him and smile. I didn’t believe it.

Two summers passed. My mother and sisters and I were ready to dispose of Dad’s ashes. We went to Truro’s Coast Guard Beach, where he loved to cast for blues and pray for a blitz. We walked across the sandbar and into the surf and poured the ashes into the sea. A fish jumped. We watched the gray cloud of ash roll in and out until the water was clear again.

By the following summer, we’d grown used to Dad’s absence. On the Cape again, my husband and teenage sons went fishing for striped bass. And when my younger son, Johnny, caught a small bluefish, he moved to throw it back in. My older son, Joe, stopped him.

“Keep it,” he said. “We’ll smoke it.”

In college then, Joe already loved to cook. He surveyed the family to figure out Dad’s recipe.

“It was a wet brine,” my husband said.

“Definitely a dry brine,” my sister said.

“I remember him squeezing limes on the filets,” I said.

“No limes,” my mother said.

Joe soaked the filets in a wet brine that included peppercorns, bay leaves, and soy sauce.

He found the smoker in the shed, covered in cobwebs, and beside it a bag of woodchips with just a few handfuls left. The bottom bowl of the smoker had rusted. Joe jerry-rigged a new bottom with some heavy-duty tin foil. He soaked the chips, wrapped them in foil, and put them over the bed of stones in the smoker. After drying the filets, he put them on the rack. From time to time, he checked the fish, not really knowing what he was checking for.

By late afternoon, the filets had turned a buttery brown. Joe took them off the smoker and let them cool. I went to the store to buy crackers and cream cheese.

The sun began to set. The windows of the houses across the marsh reflected the light like fire. Johnny put some jazz on the stereo. My husband poured the Scotch.

As Joe prepared a cracker with just the right amount of cream cheese and fish for each of us, a breeze blew across the living room, over my father’s empty chair. We tasted the bluefish and, one by one, smiled at each other in recognition. It was perfect — not too smoky, not too salty. Moist, tender, and with the faintest taste of the sea.

What follows should rightly be called “What Might Be My Father’s Smoked Bluefish Recipe.”

Smoked Bluefish

2 bluefish filets, about 2 lbs.

A quart of water

1/4 cup soy sauce

1/4 cup brown sugar

1/4 cup kosher salt

3 or 4 bay leaves, crushed

A handful black peppercorns

Catch a bluefish and filet it.

Make a brine by combining in a bowl the water, soy sauce, brown sugar, kosher salt, crushed bay leaves, and peppercorns.

Marinate the filets in the brine in the refrigerator for at least 4 hours or overnight. You can go much longer — up to 24 hours — but the longer it brines, the drier and saltier the fish will be.

Remove the filets from the brine and dry them by patting with paper towels. Set them on a baking rack (over a platter or baking pan to catch any juices) for a few hours to thoroughly dry them out.

Put the filets on the rack of a smoker (both hickory and mesquite chips work well) and let them smoke for about 3 hours at 150 degrees. When it’s brown and shiny and seems done, it’s done.

Karen Dukess is the author of the novel The Last Book Party, set in Truro in the summer of 1987. She lives in New York and spends as much time as possible at her family’s house in Truro.