For her fourth solo album, Silver City, Amy Helm had a muse: a young fan. “The first time I met her, she was in the deepest, darkest throes of addiction,” says Helm. The second time was eight months later. “I saw her across the room at a show, and I could tell she had gotten herself together. She was clean and centered. She was very proud of herself — I could see it on her face. She looked beautiful.”

The two took a picture together. About a year later, Helm found out that the woman had relapsed and died of a fentanyl overdose. Helm, heartbroken, wrote a song for her: “Young Katie.”

In the end, that song didn’t make it onto the album. “Conversationally, it didn’t hold the others,” says Helm. “It’s heavy and stark and needs to live in its own place.” But it was the catalyst for the rest of Silver City. While writing it, Helm thought about vulnerability. She thought about overcoming — and not. “Once I wrote that one, the others seemed to rush in.”

“It’s a fascinating thing,” she says, “how an album reveals, to the people who are trying to make it, what it wants to be.”

Silver City is a novel in 10 disparate songs, like chapters. Helm’s voice is a silvery whisper or a soulful cry; it sways with the gentle rocking of piano and guitar or surges forward on the back of a rock-and-roll band. Each song is a story about a woman in Helm’s life or about a season of her own life as a younger woman.

Helm will perform songs from the album on Saturday, Oct. 12 at the Payomet Performing Arts Center in Truro.

Music is a powerful tool for storytelling, says Helm, “because it’s accessible.” A person doesn’t have to be a musician to claim a song for herself, she says. “We can all clap a beat and hum along to something. It’s innate in all of us.”

For Helm, the craft of songwriting can be similarly instinctual. A verse emerges as if out of some inner fog. The chorus reveals itself in one way or another. “It has to feel like something that has enough melodic weight or narrative weight to be repeated,” she says. Sometimes she gets it wrong the first time: “What you think was your chorus is just not.”

She challenged herself with Silver City to complete songs on her own, without guidance. Alone in her living room, she’d work out the melodies.

Helm remembers having a block while writing “Silver City,” the title track. “The beginning of the song came tumbling down and out into my hands and the piano keys, and then I got stuck.” That one was painful to write, she says — it describes the time when she was going through a divorce. She wrestled with the song for a while. Then it came unstuck. “If you surrender to the process,” says Helm, “things seem to drop in.” The finished song is crooning, plaintive, and forward-moving.

She had the same experience writing other songs for the album. She allowed herself breaks and gave the songs some space. “It’s funny how much the writing process needs that,” she says. In those pauses, she would draw “really bad trees” with a pencil on a sketchpad.

Helm grew up in New York City and Woodstock, N.Y. She’s the daughter of singer and songwriter Libby Titus and drummer and vocalist Levon Helm, who played in the Canadian-American rock group The Band, which was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994 and in 2008 received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. The Band broke up in 1999, and Levon Helm went on to a successful solo career, winning multiple Grammy awards in the folk and Americana categories. He died of throat cancer in 2012.

Amy Helm recorded Silver City at Levon Helm Studios in Woodstock, where she lives now. She recorded with two core groups of musicians, both anchored by producer Josh Kaufman on guitar, bass, and keyboard.

Her family legacy has been both blessing and curse, says Helm. “My dad was one of my greatest mentors and a huge part of my musical education,” she says. “He taught me to never take a personal check from a venue and to try to get paid before the gig.”

Now, as the mother of two boys, one of whom is becoming a musician, she thinks of legacy as “something that can force us to accept ourselves for better or for worse.”

And legacy, blessing or curse, is something that must be preserved. Storytelling is one way to do that. In Silver City, Helm preserves women’s voices — some of which have been hidden until now.

“The invitation for women to tell their stories in any capacity, as rulers, housekeepers, mothers, construction workers, botanists — any job and any socioeconomic class and any period of time in the world — has been hugely diminished compared to that of men,” says Helm. There’s often a culture of secrecy among women, she says — “I wonder if it’s fair to say that women’s stories have been guarded in some way.”

A few years ago, she was in Marvell, Ark., performing at the Levon Helm Down Home Jubilee, a concert celebrating a 2019 restoration project that had moved her father’s childhood home from its original place “way out in the country” in Turkey Scratch to the center of Marvell. The home, which in 2018 was added to the Arkansas Register of Historic Places, would become a museum that honored his contributions to American film and music. “There’s an incredible bronze bust of him,” says Helm.

The house itself was a sharecropper’s cabin: long and low. “My family lived this astonishingly difficult life,” says Helm, “with no electricity and no running water. Families were losing kids to something that would be a quick trip to the pediatrician today.”

At the Jubilee, Helm stood on that house’s porch performing songs by The Band. “It’s cool that we’re honoring him,” she remembers thinking. “But on the other hand, I can’t believe my grandmother sat on this porch with six kids and got up at four in the morning and cooked meals for the family before the heat came on too strong. Then she went out and picked cotton for six hours. How did the women do this? There are a whole lot of stories from the women who sat on this porch that are not part of this celebration.”

That revelation on the porch inspired her to write “If I Was King,” a partly fictionalized narrative about her great-grandmother, who married a preacher and started having children at 14. “Her story was lost to the family,” Helm writes in a statement on her website about the album.

It’s an exciting feeling, says Helm, when you know you’ve landed on the heart of a song. “It’s the best evidence for a higher power that I’ve ever experienced,” she says. “It’s completely mystical, and yet it feels completely natural as it’s happening.”

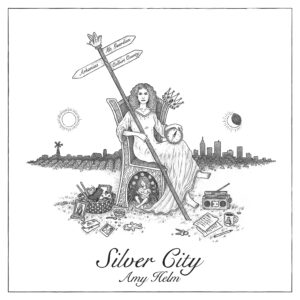

On the cover of Silver City, Helm sits on a throne. The art is by Will Lytle, who lives in Woodstock. Helm is surrounded by the physical evidence of her storied life and other women’s. “There’s a Nintendo controller,” she says. That, among other things, represents her kids. “There are my gig boots, drumsticks, a boombox.” There’s a mug and handwriting on paper.

A little girl sits cross-legged under the throne. Helm seems to protect her, but the girl doesn’t look afraid. She looks happy where she is. The adult Helm, staring steadily forward, holds a signpost in her hand.

Telling Their Stories

The event: Amy Helm performs songs from her newest album, Silver City

The time: Saturday, Oct. 12, 7 p.m.

The place: Payomet Performing Arts Center, 29 Old Dewline Rd., North Truro

The cost: $38-$55 at tickets.payomet.org