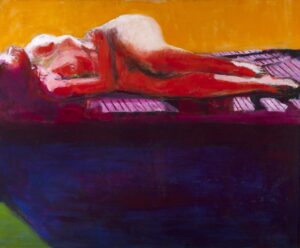

Walking into the Shirley Gorelick exhibition at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, one is “knocked out with color,” as exhibition curator and PAAM CEO Christine McCarthy puts it. Many of the paintings are grounded in observations of the figure, rendered in loose, painterly gestures. The colors range from moody, dark blues to vibrant reds and oranges.

Gorelick was born in Brooklyn in 1924. In high school, she studied with Chaim Gross, Moses Soyer, and Raphael Soyer. Later, at Brooklyn College, she studied with architect Serge Chermayeff. As a college student, Gorelick was rebellious and often pitted herself against her teachers’ ideas. In one instance, Chermayeff insisted that her painting should be in a “crisp, clean” frame. “And I felt the frame had to conform to the painting,” Gorelick told Dorothy Sees Seckler in a 1968 interview. “So, I textured it. And we had a big fight. And he said, if you don’t take the frame off, you can’t hang it. And I refused.”

Later, she would become Chermayeff’s assistant.

When Gorelick arrived in Provincetown in 1946, she was still defining her artistic sensibilities, she told Seckler.

“I knew that I wanted to do the human figure,” she said, “I just couldn’t find a style that did it for me. I was searching for a long time.” Some of that search is evident in the exhibition. The paintings on display pull from different 20th-century stylistic movements including cubism, realism, and abstract expressionism.

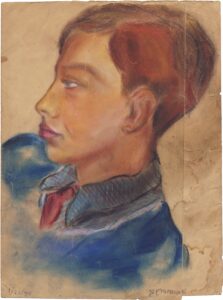

The exhibition includes paintings from the late 1930s to the 1980s. The earliest work, Jack Fishman, is a pastel portrait of her brother done in 1939, just six days after Gorelick’s 15th birthday. Works from the late 1940s, some done in Provincetown, show Gorelick experimenting with geometric forms observed in architecture.

Gorelick maintained a relationship with Provincetown after studying with Hans Hofmann. Along with a group of artist friends, she owned a place in the back of Lands End Hardware on Commercial Street. The group included Ed Weiner, a prominent jewelry designer, and his wife, Doris Weiner, an art dealer. Gorelick witnessed the debates between abstract artists and realists that defined the dialogue among artists of her era. “It was a small enough artistic community that you could actually have a debate, and all the participants were right there,” says her daughter, Jamie Gorelick.

By the 1950s and ’60s, which is the emphasis of this show, Gorelick settled into work influenced by abstract expressionism and Hofmann’s ideas about color. Some of these works are purely abstract, but in paintings like Blue Seated Figure she merged abstraction and representation. In Fragment III, a painting from 1984 of the Gorges du Verdon in France, Gorelick created a highly detailed landscape painting with a brush the size of an eyeliner pencil, but even here the focus on topography and the cropping of the landscape introduce elements of abstraction.

Fragment III is an outlier in the exhibition, but it represents a visual language she adopted later in life. Gorelick wouldn’t stay settled in the language of abstract expressionism for long, although an interest in the figure remained with her throughout her life. In the late 1970s, she painted highly realistic, penetrating psychological portraits of subjects rarely depicted in art at the time — middle-aged women, a biracial family, older couples. The portraits were often large in scale and incorporated multiple figures.

When Gorelick died in 2000, Jamie says, she “had no idea what this legacy was or how to deal with it.” In recent years, the art world has been reconsidering that same question — for Gorelick and a growing cohort of female artists who struggled for recognition. Though her art was exhibited widely and praised by reviewers during her lifetime, her legacy has taken on new life, especially after the Eric Firestone Gallery in New York City decided to represent her. The gallery specializes in uncovering under-recognized artists, many of them women. Gorelick had a major posthumous show at the gallery in 2022, and she has an upcoming solo exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in 2026.

“In the past, I couldn’t get into galleries because I was a woman,” Gorelick wrote in an undated artist’s statement. “But today, more attention is being paid to female artists, and many women are being involved in projects they never dreamed they could be.” The situation has only improved since she wrote those words.

For McCarthy, Gorelick’s movement from style to style wasn’t just to figure out what she liked best. It was reinvention. Gorelick’s later realism isn’t her “best” work — it’s the work that received the most attention. “I really admire an artist who’s not afraid to take risks,” says McCarthy. “I see Shirley as someone who’s bold and fierce.”

After a period of “reading and watching and digesting and thinking,” McCarthy visited Jamie’s house in Wellfleet to see Gorelick’s paintings in person.

McCarthy did not choose any of Gorelick’s psychological portraits for this exhibition. “I think the portraits are extraordinary,” McCarthy says. “But I don’t think enough people have seen this piece of her, and that’s what I wanted to show.”

Despite her fierceness, Gorelick had great anxieties. The night before shows were always stressful. Once, she redid an entire painting.

“Shirley chose artistic integrity over commercial success, but she also sought recognition from the art community,” Jamie said the day after the opening at PAAM. “Many of those who were there last evening used phrases like ‘previously unrecognized.’ She would have loved being seen in the way that she was last night.”

Director’s Choice

The event: Shirley Gorelick in Provincetown

The time: Through Sept. 1

The place: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St.

The cost: General admission, $15