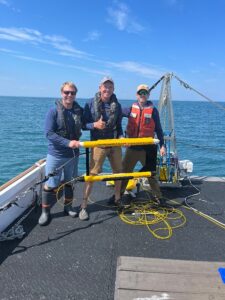

PROVINCETOWN — At first, the three men on the 40-foot F/V Heidi Lyn didn’t see any signs of debris on their consoles. Since being launched at MacMillan Pier, sonar scanners had yielded only images of grainy sand. Then the lobster boat’s captain, Chris Townsend of Truro, glanced at a second monitor.

He saw structures “like keels or backbones of boats,” he said. “A few were distinguishable as boards or logs.” The debris was what his two passengers, Stellwagen National Marine Sanctuary project manager Mike Bailey and sonar engineer Ben Roberts, called “hits or anomalies” — possible remnants of marine heritage on the seafloor.

It was May 2024, and Townsend was one of four fishing captains participating in the first year of the Stellwagen Mapping Initiative, which uses modified sonar technology to map the seafloor of Stellwagen Bank, a federally designated marine sanctuary just north of Provincetown. Sanctuary staff contracted with local fishing captains for the mapping trips, hoping to take advantage of their long experience on the bank.

“It’s like surveying the moon, and we’re looking for the lunar lander,” said Calvin Mires, a shipwreck archeologist and member of the Stellwagen Bank Advisory Council who helped coordinate the project. “These fishermen are out there every single day, and they know where more wrecks are than anybody else.”

Last year, four previously unknown shipwrecks and two other possible remnants were discovered on Stellwagen Bank, Sanctuary Supt. Pete DeCola said. The Marine Sanctuary announced the discoveries at its public advisory council meeting on Feb. 12 and provided more detailed descriptions of the sites to the Independent.

Only one of the six wrecks has been positively identified so far: the F/V Flip Out, whose name and home port of Buzzards Bay are clearly visible on its stern. The 33-foot commercial fishing vessel, which is recorded in Div. of Marine Fisheries records as having fished for Atlantic mackerel and striped bass, is believed to have sunk in 2023 with no known loss of life, Bailey said.

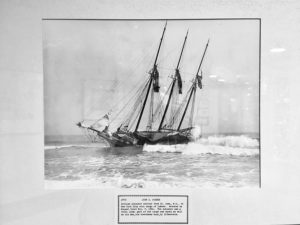

About 200 ships are known to have sunk within the boundaries of Stellwagen Bank, according to historical records, DeCola said. Since Congress authorized the sanctuary in 1992, archaeologists have located and identified 47 of them.

Those 47 wrecks represent “a 30-year haul,” said Mires. “Finding potentially six new sites within 10 days kind of blows that out of the water, pardon the pun.”

The new wrecks were found on only three trips: one from Provincetown in May, one from Gloucester in July, and one from Scituate in September. The vessels scanned uncharted areas of the seafloor, making some detours to visit locations where fishermen suspected wrecks to be.

“In fishing, those are called hangs, meaning there’s a wreck or a rock on the bottom,” Townsend said. Replacing fishing gear caught and lost on a “hang” can be costly, and many times, fishermen believe they know precisely which wreck has snagged their gear.

“I’ve always told everybody I’m a pirate by trade,” said Townsend. “For me to tow that thing around and imagine all of the stuff that had gone on in the history of our oceans was just like a childhood dream.”

Sonar Advancements

There are several reasons to map the seafloor, DeCola said. “Under the National Historic Preservation Act, it’s our job to find cultural resources underwater in national marine sanctuaries when resources allow.” The wrecks can also become vibrant ecosystems for marine life and hazards for fishermen.

Between 1992 and 2024, NOAA surveyed less than 19 percent of the National Marine Sanctuary’s seafloor, Bailey said. The new mapping initiative covered another 3 percent in just three trips.

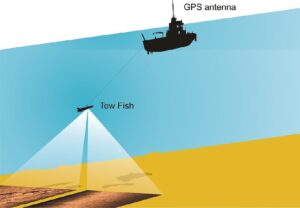

Seafloor mapping used to be done by specialized research vessels with high costs and lower image quality, Bailey said. With towable “side-scan sonar” that sits below the surface, researchers can get better images in rough water.

Sonar imaging works like an “acoustic camera” on the seafloor, collecting data on the basis of sound-wave feedback. In 2018, Roberts developed a neutrally buoyant towfish with lightweight cables that could absorb sea surface motion and be easily mounted on smaller vessels.

In November, the sanctuary partnered with Evan Kovacs of the Bourne company Marine Imaging Technologies to use a remotely operated vehicle to take photographs rather than some of the wrecks that had been identified by sonar.

The mapping initiative was funded by a one-time $1.1-million Congressional earmark sponsored by senators Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey in 2022, Bailey said.

It is not funded through NOAA’s operating budget — which the Trump administration has announced will be radically cut later this summer.

Details of the Wrecks

The Flip Out was discovered last September less than a dozen miles north of Provincetown on the mapping initiative’s Scituate trip with Capt. Phil Lynch. They were searching near the spot where Lynch’s old boat, the F/V Kathy Elizabeth, had sunk in 2006.

“Here we were looking for some 20-year-old shipwreck and instead we found a brand-new fishing boat, a complete surprise,” Bailey said.

The sanctuary reported the wreckage to the U.S. Coast Guard in Boston in October, Bailey said, but received no further details on how or when it could have sunk. The remotely operated vehicle footage identified the boat and home port.

The DMF records the Flip Out as belonging to Philip Torrance Jr. of Carver, whom the Independent was unable to reach by phone. On April 14, his sister Donna Leahan confirmed that Torrance is alive and well and owned the Flip Out when it sank.

The other wrecks are more mysterious.

According to the marine sanctuary’s shipwreck logs, “Unidentified Shipwreck — Target #11,” discovered on Oct. 4, 2024, is a “mostly intact and upright” vessel, approximately 25 meters in length. Photos from Kovacs’s submersible robot show multiple fishing nets caught on the wreck; gilded plates and cups gleam among broken wooden planks. The sanctuary has not located any records tied to the wreck, and its identity is dubbed a “mystery.”

Mires thought the design of the tableware suggested a 20th-century wreck, but he said that’s only a hypothesis. The boat “might very well be 19th-century,” he added, “when we get down there and really look at it.”

“Target 4,” another unidentified ship composed largely of scattered debris closer to Provincetown, could be the F/V North Sea, which sank nearby in 1980 with no loss of life, according to the sanctuary’s shipwreck logs.

“Target 7,” meanwhile, has a “semi-intact wheelhouse” that is now populated with fish, anemones, and other marine life.

Mires noted that each discovery is a record of loss — of livelihoods, and sometimes of lives. “This program is not just looking for shipwrecks for the sake of looking for shipwrecks,” he said. “There’s somebody’s life under the sea.” The aim is “exploration and understanding where we came from, both far back in the past and our recent past.”

Shipwrecks help serve that purpose as “relics, artifacts, and memorials,” he added.