EASTHAM — In the hierarchy of Cape Cod shellfish, the story of the clam is often forgotten in favor of the glamorous Wellfleet oyster. Across the country and the world, menus boast oysters hailing from the Outer Cape. Why not give the clam its moment in the sun?

shellfish

AQUACULTURE

‘Use It or Lose It’: Making Way for New Shellfish Grants

Lottery set for two Egg Island plots, with two more on Indian Neck soon to follow

WELLFLEET — When Nancy Civetta was hired in 2017 as the town’s shellfish constable, she was given a clear directive: “enforcement, propagation, and communication,” she said. Civetta took it to heart.

“I have been poring over the regulations ever since,” she said, which has “taken a long time and a lot of work.”

One of the two legal ways a person can lease a $25 per-year per-acre shellfishing grant — a plot of bayside bottom on the flats — is through a lottery. The rules state that a lottery is to be held to reallocate a grant that becomes available when a shellfisherman either gives back or forfeits his or her license to the town, which owns the flats that comprise 135 grants in all.

The catch is that, historically, lotteries have been rare. Before Civetta was hired, “nobody remembers it ever happening,” she said. Instead, as the Independent reported in 2019, grants were passed down to children or coworkers or quietly sold, though officially in such cases grant holders were selling their gear, not the grant itself.

These practices have impeded entry of the next generation of willing shellfish farmers into the industry, Civetta said.

The other way a newer shellfisherman can obtain a grant is by working as an employee of another farmer in the hope that one day the grant will be passed down. Even then, “it’s not a given,” said Civetta.

Gradually, newcomers are finding their way in here. In 2018, the first lottery in over 18 years was held to reassign a three-acre grant on Indian Neck. There were 12 applicants; the grant went to Justin Lynch, who later added Eben Kenny as joint grant holder.

Now, another lottery will be held on Dec. 20 for two 0.92-acre grants on Egg Island. And at the Nov. 29 meeting of the shellfish advisory board, Civetta announced the opening of two more three-acre grants on Indian Neck.

This was a surprise. “I didn’t think any would come up in the future,” advisory board Vice Chair Tom Siggia said. “Then all of a sudden, here are two from Egg Island and a couple from Indian Neck.”

The reason, said Town Administrator Rich Waldo, is enforcement. “The town has been doing a better job of enforcing the regulations than it has in years past,” he said.

One regulation in particular has led to the forfeiture of underused grants. The Evidence of Productivity clause, also known as the “Use It or Lose It” rule, requires each grant holder to spend $1,000 on seed and gear during the first three years of holding a license and to produce a minimum of $1,000 worth of shellfish per year per acre after that.

According to Civetta, if an oyster goes for 50 cents a pop, “that means you have to sell 2,000 oysters a year,” which is “very reasonable.”

“It’s practically nothing,” said shellfisherman Andrew Jacob. “You could meet the requirement in one week.” He added that “a lot of grants have just been sitting there.”

When a grant holder does not meet the minimum, the shellfish dept. sends a letter. An appeal hearing may be requested within two weeks.

But the previous holders of grant #95-15 on Egg Island, which is in the Dec. 20 lottery, never appealed. Luene and Schooner Grady had not been meeting the minimum for more than a decade, and the shellfish dept. began warning them in 2017. At a June 7 hearing, the select board voted for forfeiture.

The other grant on Egg Island, #95-16, has never been used. Civetta discovered it sitting empty while visiting the Gradys’ grant.

One of the two grants on Indian Neck was previously leased by the Dennis-based Aquacultural Research Corp., which was forced to give up the grant after the select board determined last summer that it did not meet the domicile regulation, which requires all grant holders to have lived in Wellfleet for at least a year.

The other available grant on Indian Neck was forfeited because of the minimum productivity requirements, Civetta said. It had been held by Buddy and Allison Paine.

Some see the regulations as unfair. William “Chopper” Young, who works two three-acre grants on Indian Neck, said that Civetta does her job “very correctly. Some might say she does it too correctly.”

Young has also been cited by the shellfish dept. for failure to meet the minimum. He was allowed to keep his license on the condition that he increase productivity.

Others think change is long overdue. “Nancy has done a really good job to get new opportunity for young people that are trying to make a living,” said Andrew Jacob. “It’s really challenging as a young person to make it out here. It seemed like they gave all the grants away in the ’80s. The word around town was that they weren’t making any new ones.”

Securing his 1.5-acre grant near Blackfish Creek six years ago was life-changing, Jacob said. “The second I got an oyster farm, I had stability,” he said, “and I was able to buy a house a year or two after that. It was a game-changer. You can make a living off an acre. Even half an acre. Most people who have a big oyster farm are only using a small portion of it.”

Siggia agrees that enforcing the rules is important. “We want to make sure we’re keeping the young adults here in Wellfleet by giving them an opportunity to start a business,” he said.

At press time this week, the town had received four complete applications for the Egg Island lottery. But Civetta said she thinks more would be submitted before the deadline on Dec. 7.

The shellfish dept. will announce the lottery for the two Indian Neck plots after the shellfish advisory board makes its recommendations on grant sizes and the select board establishes them.

“It’s important that our cultural heritage is passed down and that new opportunities open up,” Civetta said. “The lottery process is our ticket to that.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, published in print on Dec. 8, incorrectly stated that an aquaculture grant was awarded by lottery in 2018 to Justin and Melissa Lynch. The award went to Justin Lynch alone. The earlier version also incorrectly reported that the shellfish dept. would establish grant sizes before the next Indian Neck lottery; the select board will make that determination.

AQUACULTURE

A Bad Year for Shellfish Seed Sows Discontent

Facing shortage, shellfishermen question Wellfleet's revocation of A.R.C. grant

WELLFLEET — Shellfisherman Bob LaPointe is grateful he will be able to grow half his usual crop of oysters and clams this year. That’s because Island Creek Oysters, one of only two hatcheries in the state, canceled its seed sales altogether, while the other, Aquacultural Research Corp. (A.R.C.) of Dennis, offered only limited quantities after losing two seed sets earlier in the year.

ENVIRONMENT

Searching for Alternatives to ‘Beach Nourishment’

Oystermen say ‘sacrificial sand’ is burying their shellfish grants

WELLFLEET — To preserve eroding property and maintain beaches, thousands of cubic yards of so-called sacrificial sand is piled on coastal banks and bay shores here. It does not stay put. Local shellfishermen say finding new ways to fight erosion is urgent because the sand that has been piled along 36 waterfront properties from Indian Neck to Blackfish Creek is burying their oyster grants and smothering native grasses.

“We’ve watched them, year after year, bring truckload after truckload of non-native sand to fill this hole,” said shellfisherman Brad Morse, pointing to an eroding cliff off King Phillip Road. “With the next set of high tides, it’s gone.”

Morse, who has a shellfish grant near the tip of Field Point, and Kurt Graham, who has a neighboring grant, have been attending conservation commission and select board meetings to let leaders know that the “sand is ruinous.”

“My grant used to be a steamer grant before I got it,” Graham said. “You don’t see steamers down here anymore.” Graham has tried seeding both steamers and quahogs, but the sand “covers all the clams and kills everything,” he said.

Morse said he’s been trying to grow oysters on his grant since he got it in 2009, but “it’s almost impossible there,” he said. “They always get covered in sand and die over the winter.”

Select board member Michael DeVasto has a shellfish grant next to Morse’s. On a recent morning, DeVasto walked across an expanse of sand to reach a buoy he uses to mark the row of racks that hold the bags of oysters he is raising. Because of sand accumulation, the usable flats are farther from the shore than they used to be, he explained, as he dug down through a foot of sand to reach the pipe that anchors his buoy.

It Started With Revetments

The practice of dumping sacrificial sand is called “beach nourishment,” and it began as a response to problems posed by the construction of revetments — stone or concrete walls — meant to protect properties along the shore from erosion. Now, the sand — including 2,000 cubic yards dumped on the coastal bank at the Blasch house on Chequessett Neck Road in 2019 — is also being used in an attempt to prevent structures from collapsing over cliff edges.

By the 1970s, it was clear that revetments were altering natural sedimentation, leaving beaches with sand deficits and increased erosion and destroying habitats needed by piping plovers and diamondback terrapins, said Health and Conservation Agent Hillary Greenberg-Lemos.

That’s when scientists got together and worked with the state to come up with the Wetlands Protection Act, according to Barnstable County Coastal Process Specialist Greg Berman. “The idea was, if revetments continue, we’re not going to have beaches, dunes, marshes, and shellfishing areas,” he said.

The act barred the further construction of revetments. It also requires property owners who have old revetments to add sand to the surrounding banks according to an equation that, Greenberg-Lemos said, takes into account the height of the bank, the size of the revetment, and the erosion rate, which is difficult to calculate year to year.

The owners of each of the 36 properties along the Indian Neck to Blackfish Creek stretch of shore typically have to apply between 80 and several hundred cubic yards of sand each winter, theoretically replacing what has been lost because the natural sedimentation processes were interrupted by their revetments.

The theory isn’t proving to be correct, Berman explained, because sacrificial sand doesn’t have any vegetation or roots that might slow down erosion. It moves swiftly, and, in the Field Point area, for example, aided by existing revetments, it is pushed down to the end where DeVasto’s, Morse’s, and Graham’s grants are.

‘Catch-22’

The Wetlands Protection Act can be a fairly blunt tool, Berman said, “so we have to get a feel for how we can live with what’s being affected by these structures.”

“It’s a catch-22,” Morse said. “If they had never allowed walls, the sediment would be natural.” Morse and other shellfishermen argue that, in some places, including along the King Phillip Road properties, it would be better to allow the walls to be finished.

The problem is “tricky,” with competing stakeholders, Greenberg-Lemos said.

In her view, “Sand is the best solution because there’s no structure. It’s natural. It ebbs and flows.” But she sees its effects on both shellfishing and boating and agrees further evaluation of the problem is needed.

Gordon Peabody, director of Safe Harbor Environmental Services in Wellfleet, has volunteered to gather data that should help such an evaluation. He proposes to record the shifting elevations along the coast.

“It’s a tidal and storm-driven process,” Peabody said, adding that it’s important to know more about how the sand moves from one area to another. “It’s up to us to figure it out,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Wellfleet Conservation Commission is working “to try something new,” Greenberg-Lemos said, though possible alternatives are just starting to be explored.

One solution could be to try adding less sand and transition the King Phillip Road site to a salt marsh project, Greenberg-Lemos said. Another solution would be to take a more holistic view of where the required sand should be placed. “We’re trying to evaluate the best places to put the sand to benefit the system,” she said. “I hope to have more defined answers about that ongoing work soon.

“Coastal banks are going to continue to erode,” said the conservation agent. “The fishermen are going to have to figure out other ways to fish over time. Property owners are going to figure out what they’re going to do. We all need to get along to make it work.”

ECONOMY

E.U. Markets Reopen to Outer Cape’s Shellfish

The benefit to local growers will come slowly

WELLFLEET — Shellfish from Outer Cape Cod may soon make its way to Europe again after a 12-year hiatus. What that means for local growers is not yet clear, but so far at least one wholesaler here is working to make the overseas connections that would allow Cape Cod oysters and clams to appear on tables in the European Union by next winter.

Alex Hay, president of the Wellfleet Shellfish Company in Eastham, says it will take time, but he anticipates that reopening trade with the E.U. will be “a good thing for everyone.”

The shellfish trade between the U.S. and the European Union ground to a halt in 2010 because of a dispute over differences in food safety controls. But on Feb. 27, European markets reopened to wholesalers from Massachusetts and Washington state. Sellers in other states will also soon be eligible to export, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

At the same time, we may be seeing mussels coming here from Spain or the Netherlands, both significant producers of those mollusks, as those two countries will now be allowed to export shellfish to the U.S.

This reopening concludes more than a decade of back-and-forth “dithering” over whether the safety controls imposed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are equivalent to the system used by the E.U.’s food safety regulatory authority, said Bob Rheault, executive director of the East Coast Shellfish Growers Association. Rheault, based in Rhode Island, has spent the past 12 years urging policymakers in Washington, D.C. to reopen the European market to producers here.

“The main hangup was that the E.U. samples their shellfish meats,” he said, “while our sanitation program is based on sampling the waters.” Statisticians had to sit down and look at the two different programs, he said, and in September 2020 the U.S. and E.U. finally agreed that their safety control systems were equivalent.

Rheault doesn’t anticipate a “gold rush” into the E.U. anytime soon. He said he is not even sure what the European market is worth to American sellers. “All I can say honestly is that, before things closed, we were shipping somewhere between $1 million to $3 million worth of clams to Spain per year,” Rheault said, referring to Rhode Island clam growers.

Hay said he also is unsure of the European market potential. But he sees expanding into Europe as a way to “keep the pressure off of local markets,” where prices can drop if supply exceeds demand. He said that’s why his business already focuses on distributing widely beyond Cape Cod. With the E.U. reopening, his hope is to further improve prices for local growers.

That’s likely going to take some time. While trade officially resumed last week, Rheault estimated it will be months before shellfish distributors can fly oysters, clams, mussels, and scallops across the pond.

Massachusetts companies now face the task of transatlantic relationship-building — or, as Rheault put it: “Sending over an emissary to kiss the right ass and pay the right money to get the right customs broker so that your stuff doesn’t end up rotting on the docks for two weeks.”

Searching for that customs whiz will mean schmoozing around seafood expos in Brussels and Barcelona, and wholesalers will also need to negotiate credit lines and quantities with European buyers.

“Flying live rocks around the planet is heavy, not to mention expensive,” Rheault said. “If you’re going to make this work, you need to be sending a whole pallet — which is roughly a ton.”

Stateside, there’s plenty of red tape, too — namely going through a federal seafood inspection created especially for the European market and nailing down various certificates that qualify a distributor for export.

Chris King, owner of Cape Tip Seafood, a Provincetown wholesaler, says he is not interested in gearing up to sell to the European market. Instead, he says, his focus is to supply Cape Cod restaurants and markets. Holbrook Oyster, a smaller wholesaler, is also sticking to the Cape, according to owner Zack Dixon.

One reason Hay said he is hopeful has to do with the seasonality of the shellfishing industry. He said he expects prime time for exports to the E.U. to hit in the fall, between October and December — that time of year when “being a shellfish wholesaler is one of the worst jobs in the whole world,” he told the Independent.

Rheault agreed, explaining that’s when the wild harvest opens on the East Coast, ramping up competition with wholesalers, which in turn drives down the price of cultured shellfish. “The cheap product floods the market,” Rheault said. “We can’t sell the premium cultured oyster at all, not until the wild harvest gets exhausted.”

But Rheault hopes that a few years from now wholesalers will be able to send their autumn supply off just as “everybody in Europe is stocking up on oysters for Christmas.

“It was a slow-rolling train,” he said. “I certainly didn’t think it would take 12 years to get things reopened. But, hopefully, this will help create more demand and raise prices. And the phone will be ringing a bit more.”

The Off Season Is On

Shawn Quinlan of Maynard stands in the early morning light at Pilgrims’ First Landing Park in Provincetown with his catch of quahogs and oysters. (Photo Elizabeth G. Brooke)

STATE OF THE HARBOR

Shellfish Propagation Strategies Reap Promising Results

Insights from research on how to keep clams ‘happy’ and where oysters might grow

WELLFLEET — Sometime in June, a fleet of pickup trucks rumbled into the Dunkin’ Donuts parking lot and met for a handoff. Their drivers were “not making a drug deal,” said “Johnny Clam” Mankevetch, Wellfleet’s assistant shellfish constable, in a talk at the 19th annual State of Wellfleet Harbor Conference last month. “They were waiting for quahog seed.”

His talk summarized what the town’s shellfish dept. has been learning from experiments that began back in 2018 to compare shellfish propagation strategies.

Complementing the department’s work, the nonprofit Wellfleet Shellfish Promotion and Tasting (SPAT) has funded a three-year study led by biologist Barbara Brennessel. Now in year two, her research is providing insights on how tidal restoration at the Herring River may affect oyster larvae settlement.

Happier Clams

Obtaining quahog clam seed involves engaging with a “seller’s market.” For the shellfish dept., “there’s a lot of phone calls and phone messages and waiting,” Mankevetch said. And when it comes to the shipping date, hatcheries set the pace.

This year, the shellfish dept. bought 500,000 quahogs, each about four millimeters long. In June, the hatchery representative rolled into Wellfleet with half the load. The other half arrived in August.

The shellfish dept. piles the seed into mesh cages destined for Wellfleet Harbor — but not without first raking the bottom for predators. “If you have crabs under your quahog netting,” Mankevetch said, “they have nothing to do but eat.” From there, the clams mature in the tidal flats, and in three years or so they’re ready for harvest.

As the tide goes out, the receding water in Chipman’s Cove uncovers loads of “happy little clams,” Mankevetch said.

Wellfleet’s supply of happy clams comes not only from hatchery seed purchases but also from a quahog relay program based in the Taunton River — “a wonderful quahog growing area,” according to Mankevetch, “that’s mildly yet hopelessly contaminated with fecal coliform.”

These Taunton River clams are off-limits for harvest. “But when they’re put in clean water, the shellfish will continuously filter and flush out the bacteria,” said Brennessel, a Wellfleet-based biologist who has served on the town’s shellfish advisory board and conservation commission.

Wellfleet purchases these contaminated quahogs in June for around $20 per tote, and the shellfish are dispersed in the harbor. Within a few days, the clams pump out the coliform and can be state-certified for consumption — but Wellfleet keeps them undisturbed through their spawning period.

“This is important,” Brennessel said. “It’s not like you put them there, and as soon as they’re clean, you harvest them. They’re left there long enough that they can spawn and make more shellfish for Wellfleet Harbor.”

Harvesters can come after this spawning period ends sometime in September, and they’ve reported back this year with sightings of quahog seed. The appearance of wild seed floating in the waters is promising news, especially as littlenecks (small quahogs) have been enjoying a “historic price in the market,” Mankevetch said. “Our commercial fishermen are truly reaping the benefits of this program.”

A June Jackpot

Unlike clams, oyster larvae (also called “spat”) can cling to a substrate. When it’s spawning season, the shellfish dept. catches wild spat on plastic disks coated in lime-rich cement. Curving into wide-rimmed cone shapes, these apparatuses are called “Chinese hats,” and they sit in stacks along the harbor. Chipman’s Cove and the mouth of the Herring River are two prime spots.

The department also does “cultching,” another rendition of this spat-catching principle that involves laying down rows of empty shells in the intertidal zone, where larvae can grab hold.

Historically, shellfishermen have followed a rule of thumb: those Chinese hats should hit the water near the Fourth of July. Two years ago, however, that schedule returned a meager catch. But the few who happened to deploy their devices in mid-June landed a jackpot, so, this year, spat collection kicked off by the second week of June, and the hats “caught magnificently,” Mankevetch remarked. “You could hardly lift them off the bottom and put them onto the truck.”

When they first stick onto the hats, young oysters have grown only one shell. By the end of September, the back shell forms, and soon after they’re ready for mesh growing bags. In theory, to do this “you just flex the disk, and they pop off,” Mankevetch said. “It doesn’t really work that way all the time. There’s a lot of banging involved.”

From there, the oysters return to the tidal flats, where they’re grown in bags until they hit market size — or until January, when the threat of harbor icing looms. Ice can churn up equipment and devastate an oyster grant. “We all live in abject fear of ice,” Mankevetch said. “If you leave your racks and bags out in the ice, it creates an outrageous, unfathomable mess of twisted rebar.”

At this point, hundreds of thousands of oysters take refuge at the dump — that is, they’re hustled out of the winter waters and thrown into an oyster pit under the auspices of the town transfer station. In early March, “you take them out and they sound dry and rattly,” Mankevetch said. “You go, ‘Oh, no — these are all gonna be dead.”

But once the oysters return to the water, “they refresh,” he continued. “They’re alive, the great majority of them. I’ll never stop being amazed at that.”

Hope Upstream

With the Herring River Restoration Project in the near future, shellfishermen have been wondering how tidal restoration in the river’s basin may change where spat settles in Wellfleet Harbor.

“I realized that no one had studied it,” Brennessel told the Independent. “It wasn’t scheduled to be part of all the other studies that were done as part of the restoration,” she said, adding, “It seemed to me like a simple enough thing to get some baseline data before the restoration.”

Working through the Friends of Herring River, she proposed the idea to SPAT — the nonprofit that organizes Wellfleet’s OysterFest and supports research and education on the ecology and economy of shellfishing and aquaculture here — and received a grant to pursue it.

Aided by retired National Seashore ecologist John Portnoy and Silas Watkins, who was still a student at UMass Amherst in the project’s first year (he has since graduated), Brennessel wrapped up the second year of her Herring River estuary spat settlement study in September.

The team collected spat from four sites along the estuary. For comparison, they also monitored settlement at Jake and Irving Puffer’s Mayo Beach grant, which reliably catches wild oyster set.

This year, they found that spat could settle on the site just landward of the Herring River dike. But at a spot National Seashore scientists call the Dog Leg, the last place where salt water reaches upstream and which experiences far less tidal flushing, they found none.

“I hypothesize that, with restoration, there’ll be increased settlement further upriver,” Brennessel said. “And that the conditions will be more favorable for the growth of oysters above the dike.”

THE DREDGE REPORT

Shellfishermen, Scientists Study Wellfleet’s Goo

‘Black custard’ isn’t toxic, but it can be perilous

WELLFLEET — Chopper Young was working on his oyster grant one day when a shrill note pierced Chipman’s Cove. Stranded in the mucky tidal flats was a woman in a kayak. She puffed on her whistle, over and over. “Fire and rescue were down there already,” Young said, “but they couldn’t reach her.”

He decided to take matters into his own hands. Wading out into the gummy harbor, Young tossed the woman a rope and tugged her out of the mud.

But not without sinking in himself, said Young, “balls deep.”

PROVINCETOWN: THIS WEEK'S CURRENTS

Stranded Boat Could Delay Shellfish Season

Meetings Ahead

All meetings this week are in person at Town Hall. Go to provincetown-ma.gov and click on the meeting you want to watch to see if a remote option is available.

Thursday, Oct. 28

- Planning Board, 6 p.m., Town Hall

Monday, Nov. 1

- Select Board, 5 p.m., Town Hall

Tuesday, Nov. 2

- Conservation Commission, 6 p.m., Town Hall

Wednesday, Nov. 3

- Historic District Commission, 4 p.m., Town Hall

Thursday, Nov. 4

- Zoning Board of Appeals, 6 p.m., Town Hall

Conversation Starters

Stranded Boat Could Delay Shellfish Season

Harbormaster Don German is trying to get the owner of a wrecked 27-foot Columbia sailboat to remove it from the rocks of the West End breakwater, where it has been stuck since Sept. 2.

So far, however, owner Robert Walsh of Hyannis has avoided claiming his uninsured vessel, delaying the town’s ability to remove it, German said. He fears the recreational shellfish season, which opens Nov. 5, will be delayed because the state Div. of Marine Fisheries (DMF) will not allow the shellfish beds by the breakwater to open as long as the grounded boat is present, according to an Oct. 25 letter to the town from Dan McKiernan, the DMF director.

German said he did not know how long it would take to complete the legal process to remove the vessel.

The harbormaster said he sent a certified letter to Walsh, which Walsh has not signed for. Once the letter is returned, German can take steps to condemn the boat and then have it removed. Noah Santos of Towboat U.S.A. said that would cost $10,000 to $15,000. The town may need to take Walsh to court to recoup the cost, German said.

The boat is not leaking fuel, as the tank was removed shortly after the boat struck the rocks, German said. Nevertheless, closing nearby shellfish beds as a precaution is standard procedure under these circumstances, said Shellfish Constable Steve Wisbauer.

Cybersecurity Standouts

Provincetown and Truro were among 34 towns honored for completing training in cybersecurity awareness by the Executive Office of Technology Services and Security.

The state agency named Truro, Provincetown, Dennis, Nantucket, and Edgartown as among the state’s most “cyber-aware communities.”

The designation goes to municipalities, police, and school departments that volunteered to take a year-long training program, said Provincetown Technology Director Beau Jackett. The course is still ongoing, but the towns honored have had their staff complete a significant number of the assignments, Jackett said.

The training includes simulating phishing stings, which tests the employees’ ability to recognize signs of scams. At first, about four percent of Provincetown staff clicked on the phish bait. But no one opened the last phishing email. That is progress, Jackett said. —K.C. Myers

THE DREDGE REPORT

Race to Rescue Oysters From Dredge’s Path

Silt would put Chipman’s Cove’s ‘tremendous’ oyster crop at risk

WELLFLEET — When the dense sea lettuce in Chipman’s Cove cleared up a few weeks ago, Nancy Civetta and Johnny “Clam” Mankevetch of the Wellfleet Shellfish Dept. strolled through at low tide to judge how best to prepare for the harbor dredging set to begin on Oct. 1. Scanning the bottom, they saw an oyster bonanza.

SHELLFISHING

Temporary Moratorium Imposed on New Town-Owned Grants

Wellfleet Shellfish Advisory Board asked to recommend uses of HDYLTA Trust flats

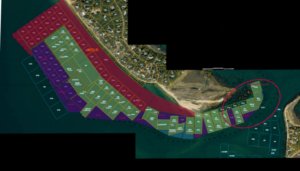

WELLFLEET — The select board imposed a temporary moratorium on aquaculture grants on town-owned flats off Indian Neck on Aug. 16, pending a review by the town’s shellfish advisory board. The select board required that the review include input from upland property owners, the marina advisory committee, and the natural resources advisory board.

The moratorium affects about 26.2 acres of unproductive bottom that could potentially be developed into new grants. That area is slightly more than one-tenth of the whole town-owned tract of 254.5 acres.

The select board added a provision that 20 of the 26.2 acres would be made available first to five grant holders who currently operate in deep water outside the town-owned flats.

Monday’s hearing, held remotely, was the town’s first stab at making policy on the tidelands since town meeting voters agreed to buy them in April 2019. The property contains a mix of wild shellfishing area, beach, wetlands, and one-third of the cultivated shellfish grants in Wellfleet.

It is rare for a town to buy land for aquaculture, said Ed Englander, the attorney who represented the four businessmen of the How Do You Like Them Apples (HDYLTA) Realty Trust who sold the tract to the town for $2 million. They had bought the flats in 1999 for $25,000.

The town’s purchase was even more unusual because half the money came from a select board member, Helen Miranda Wilson, who anonymously donated $1 million to help seal the deal; taxpayers provided the other $1 million. A public records request by the Provincetown Banner led to Wilson being identified as the donor.

Wilson, an artist who has never held a shellfishing grant, said she derived no financial benefit from the transaction but simply wanted to help the shellfish industry and protect the flats from deep-pocketed buyers.

Following the controversial purchase, town officials took no action until Shellfish Constable Nancy Civetta and Harbormaster Will Sullivan wrote a letter to the select board in April, asking for a public forum to begin planning the future use of the flats.

“We think that we should take a step back as a community and look at the question of what to do with and how to best use the HDYLTA Trust property,” wrote Sullivan and Civetta. “A holistic planning for the area seems warranted in order to bring people together to consider the effects of expanded aquaculture on other harbor users.”

During the Aug. 16 meeting, it was clear that nearby upland property owners are bothered by shellfish trucks on their beaches. Boaters said the Blackfish Creek channel is crowded with shellfish gear and difficult to navigate.

The select board’s decision to impose the moratorium specified that home owners on Field Point and King Philip Road must be included among those consulted on recommendations for use of the flats.

Select board chair Ryan Curley said the five three-acre grant holders who currently operate in deep water are having trouble making their grants profitable. They are Robert and Allison Paine, Dave Seitler and Melissa Yow, the shellfish seed hatchery A.R.C. in Dennis, William “Chopper” Young, and Justin Lynch and Eben Kenny. The area is accessible only on foot at extreme low tides.

The HDYLTA flats include 20.5 acres next to these deep-water grants. If the land is unproductive — that is, not suitable for wild shellfish harvesting — it is eligible to become private grants. That determination must be made by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the state Div. of Marine Fisheries.

Seitler said he did not attend the Aug. 16 meeting but was pleased with the offer to move his grant toward shallower water.

“It would be helpful for me; it would be helpful for the town,” said Seitler. “It seems like a win-win for everybody.” Right now, the former HDYLTA grants in Seitler’s area create what he calls a “random alleyway that nobody can use.”

Civetta said “there is a general consensus” that moving those grants landward into HDYLTA territory would be worthwhile. The deep-water grants would then be turned back to the wild, though that was not part of the select board’s formal vote.

Sullivan, the harbormaster, said returning the deep-water grants to the wild would improve navigation in “that whole stretch of land.”

Curley said he used to be able to tack in his sailboat in Blackfish Creek, but now it is too crowded with shellfish gear on either side.

Anne Sterling, president of the Field Point Property Owners Association, asked that any planning committee include residents of that area who maintain the access roads.

“There is concern about stability of the beach with all the trucks on it,” she said. “So, more grants would bring more trucks.”

Civetta said planning a few new grants on HDYLTA should be fine.

“Wellfleet has been under aquaculture for decades,” she said, “and we don’t have real problems in my eyes. I don’t think this should be a problem — to allow some newcomers to the industry.”

Reporter Alex Sharp contributed to this article.

CHOP TALK

Chopper Young Can Take Care of Himself

Wellfleet’s champion shucker on selectmen, self-sufficiency, and what winning the lottery can’t change

WELLFLEET — Chopper Young is waiting on a fish. He’s knee-deep in Sally’s Bottom (from him, this guarantees a smirk), two poles planted, a headwind niggling his lines. Six feet to his left wades Bob Kellogg, Young’s scrub-bearded, camouflaged, oysterman friend.

In two hours, Kellogg has wrangled with four bites and kept a trout. In two hours, Young has drained his Dunkin’ Donuts cup and complained about the wind. It was the wind’s fault at first, when six minutes passed and Young’s fish-in-five-minutes promise fell flat. “Hate fishing into it,” he says. “Damn near impossible.”

Then Kellogg’s line bobs once, twice. Blame shifts. “Bob’s got the good spot,” Young says. “Stole the good spot I showed him. Fishing hole’s ruined.” Kellogg lands his trout. Chopper: “Nothing special, smaller than my bait. But that’s the one that I was gonna catch.”

Another hour of disappointment, and Young comes to terms with the Gull Pond fishes’ united front. He grumbles. He wades in; he wades out. He returns to the issue of the wind. Then, he starts to catalog. His poles are store-bought, sure. But consider his pole-holders: hand-forged, by him, in ’98. Kellogg’s bobbers are red-striped, plastic, mass-produced. Young whittled his, onsite, from a pair of pondside twigs. How about a recreational fishing license? Get a load of this: he doesn’t have one. On principle.

“So, Bob’s got a fish,” he says. “But me? I’m fishing the real way.”

Chopper Young says that he has always been moustached. He is blue-eyed, burly, perpetually baseball-capped. The cap lifts, only for a second, in moments of marked animation. “Selectmen: We have to call them ‘selectpersons’ now. What a joke.” Ball cap lifts. “Biden: hope he dies.” Ball cap lifts. “The liberal mob.” Ball cap lifts.

“Women: love ’em to pieces. But God, can they alter your judgment.” Ball cap lifts. One particular woman, sashaying through the Dunkin’ Donuts parking lot in a pair of well-cut jeans. Ball cap lifts.

In 2007, 2008, and 2013, Young won the U.S. national oyster shucking title, which qualified him to compete in the World Oyster Opening Championship in Galway, Ireland the following year. In 2008, he was the world champion. At the Route 6 Express Mart in 2015, Young won $10 million on a Mass. State Lottery scratch-off ticket. None of these stories moves the ball cap anymore.

Young has called it curtains on competitive shucking. Not at the Wellfleet OysterFest level, but shucking for national and world titles. “I’m getting old,” he says, waiting for a reporter to disagree. Young is 54. He has a 32-year-old daughter and a three-year-old at home. Gray speckles the moustache. Still, he maintains that he can outshuck anyone. He swipes open an oyster, winks, offers it. “I’m damn good.”

And Young is done with scratch-offs. He opted to turn his 10-million-dollar ticket into a $6,500,000 cash option: $3.5 million, after taxes. He had his teeth cleaned. He bought his mother a house. He went on safari and brought home a wildebeest.

But when he talks about winning the lottery, Young spends most of his time rattling off things he didn’t do. He didn’t abandon his shellfish grant, or his boats, or his clamming operation. He didn’t go make a crowd of uppity friends. He didn’t buy a sports car. “Chopper didn’t change,” he says twice. “Chopper didn’t change.”

What Young, after heavy questioning, will admit did change: once in a while, he has to deal with banks. He’s bought some property. He’s bought some trucks. “It’s good not being up against the pressure of racing to pay bills, to make ends meet,” he says. He takes a breath. “And, well, it’s good just knowing you can take care of your goddamn self.”

Years ago — he doesn’t remember when, but certainly before the scratch-off — Young served as an alternate on the Wellfleet Shellfish Advisory Board. Now, he’s driving down Route 6 (“Don’t text and drive,” he says, texting and driving) when his phone dings with a reminder about an SAB meeting that night.

“No thanks,” he says, adding an expletive. “A bunch of opinionated assholes trying to tell other assholes what they can and cannot do? I don’t need that.”

Also, “assholes” are most of the shellfishermen who engage with the SAB. Pre-lottery, Young considered a select board run. Now the select board members are assholes, too: “Giving the chickens a handful of scratch while they jack up the tax rate to build an affordable colony, so our kids can stay here and be deemed welfare recipients for the rest of their goddamn lives.” So is everyone in town government. “Greedy.” So are the Democrats, “handing out paychecks, taking money from the millionaires who worked for it and giving it to the mess we’ve created — people at the bottom of the barrel.”

Young does not believe in welfare. “Handouts,” he says, “are bullshit.” Young believes in strict borders, American jobs, and keeping his head down. Young believes in being able to provide. He hunts. He fishes. He stacks wood around the Keep America Great flag in one of his front yards. He whittles his own bobbers. He grows fruits, vegetables, oysters, weed. He has Flemish Giant rabbits, which he’ll kill if he has to. He says he has most everything he needs for an apocalypse. He has a giraffe and half a zebra hide in the kids’ playroom. He has his wildebeest.

But hours into that April morning on Gull Pond, Chopper Young is still without a catch. A stranger arrives at the hole, rod in hand, and asks about the fishing.

“Damn terrible,” says Young, who had set the time (8 a.m.) and the place (Gull Pond). “If I’d had my druthers, we’d be in Orleans.”

Editor’s note: Because of a fact-checking error, an earlier version of this article reported that Chopper Young won the World Oyster Opening Championship three times. He was the U.S. national champion three times, but the world champion only once, in 2008.

AQUACULTURE

Selects Give Chair a Boost

DeVasto’s shellfish grant extension subject to constable’s inspection

WELLFLEET — The select board voted 4-0 on March 23 to approve Chair Michael DeVasto’s request that his two-acre aquaculture grant be enlarged by 1.3 acres, on two conditions: that Harbormaster Will Sullivan confirm the move will not affect harbor navigation, and that Shellfish Constable Nancy Civetta perform a site visit to assess potential conflicts with other growers or wild harvesters.

DeVasto recused himself from the discussion and vote.

Four days before the meeting, on March 19, Civetta had formally asked the board to postpone the DeVasto hearing by two weeks.

“I only found out about this hearing yesterday morning from Mike himself,” she wrote in an email. “Therefore, I have not been able to conduct a site visit to the proposed grant extension to walk the bottom (with Asst. Constable John Mankevetch), check that the buoys marking the current grant are in the accurate locations, and understand the proposed extension’s proximity to the Blackfish Creek channel … I imagine that you would want some input from the Shellfish Department about this.”

By the March 23 meeting, though, Civetta had changed her mind. “After extensive conversations,” she said, “Mike asked if we could approve — if you could approve — it tonight, based on certain conditions. After a long conversation tonight, I said okay.”

The pandemic, DeVasto wrote to the other select board members on Feb. 7, had cut revenue from his existing grant on the southern side of Indian Neck Beach, adjacent to Field Point, by 48 percent. And he wrote that it had “created an overstock of product that has resulted in lack of functional space for grow-out and room for the incoming seed.” Hence DeVasto’s proposed 1.3-acre grant extension. Immediately south and west of his farm, it would allow him to retain his current employees and maintain his operation, he said.

The area DeVasto wants to add to his grant, designated as 855C, has never been farmed before, according to select board member Helen Miranda Wilson. Both that grant and DeVasto’s current grant are part of the former HDYLTA Trust property, which the town purchased in 2019 for $2 million.

Mass. General Laws Chapter 130, Section 57 and Wellfleet shellfish regulations 7.6, 7.8.1, and 7.12.4 lay out the process for Wellfleet residents seeking new aquaculture licenses and extensions.

The license seeker must apply to the select board, which is also the town’s licensing board and shellfish regulatory board. After confirmation from the state Div. of Marine Fisheries (DMF) that the proposed grant would “cause no substantial adverse effect on the shellfish or other natural resources of the city or town,” the board can approve a grant.

Only after such approval can a biological survey by the DMF, licensing from the Army Corps of Engineers, and a MEPA review be conducted — and only after those tasks have been completed can the license seeker begin using his grant.

Postponing his hearing by two weeks would have delayed engaging with the DMF until the first week of May “due to the schedule of the select board and the requirements of DMF to have approved minutes and paperwork submitted by administration,” DeVasto wrote to the Independent. “It was important for me to get the process started as soon as possible.”

Civetta, who stressed in the March 23 meeting that “Mike did everything quite correctly according to Mass. General Law,” denied repeated requests for comment.

Wilson said that DeVasto’s request for a conditional approval was “not illegal, just unusual.”