In 1992, a year after the collapse of the Soviet Union, American television producer and reporter Natasha Lance Rogoff accepted the role of executive producer for a new project: Ulitsa Sezam, a Russian adaptation of the American TV show Sesame Street. This wouldn’t be her first time in Russia — a decade earlier, as an exchange student at Leningrad State University, Rogoff had reported on the underground arts culture there for NBC, ABC, and PBS.

In her 2022 book Muppets in Moscow: The Unexpected Crazy True Story of Making Sesame Street in Russia, Rogoff chronicles her work on the show from 1992 to 1997. She will discuss the book with Truro resident Ed Christie, a longtime staff member at the Jim Henson Company’s puppet workshop, at East End Books in Provincetown on Saturday, Sept. 14.

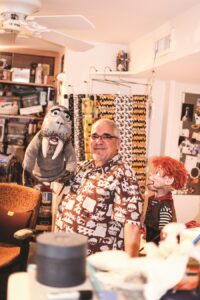

During his time with Henson, Christie designed puppets for Sesame Street adaptations around the world. “Muppets are Muppets,” says Christie. “I’ve done Sesame Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, Canada, Japan. The puppets all have the same central look: two eyes and a nose and mouth.”

Despite the Muppets’ universal appeal, Rogoff says, the Russian creative team behind Ulitsa Sezam didn’t want to recreate American-style puppets. Muppets were too weird for them. “They’re made of foam, they’re soft, they have round heads with googly eyes,” says Rogoff. “Russia has an incredibly rich tradition of puppetry. They only wanted to use traditional Russian puppets, which were made out of wood.”

Instead, the puppets Rogoff’s creative team had in mind were marionettes based on the designs of Russian puppeteer Sergey Obraztsov, who Jim Henson called the father of international puppetry. “It was a Muppet stalemate,” Rogoff says. “It went on for several months.”

The tension ran deeper than competing ideas for puppet design. During the early 1990s, relations between the U.S. and Russia were warmer than they were during the Cold War a few years before. “But the situation in Russia was extremely unstable,” says Rogoff. “It was a time of incredible upheaval.” Former republics like Ukraine and Georgia were declaring independence, and the formerly Communist country was attempting to transition to a more open, freely expressive society. Ulitsa Sezam was going to teach “open, idealistic values,” says Rogoff. The project was intended to give children the skills needed to thrive in their new society.

The plan provoked violent reactions. “Our first sponsor of the show was blown up in a car bombing,” says Rogoff. “The second one was assassinated.” Television journalist and democracy advocate Vladislav Listyev, with whom Rogoff had spent months negotiating and collaborating to get Ulitsa Sezam on the air, was assassinated, too.

“He was my confidante,” she says. “And he was shot in front of his house.” For the first time, Rogoff feared for her own life.

Despite these setbacks, progress on the production continued. “I put on a really strong, positive, confident front to my team,” says Rogoff. “I was leading about 400 artists. I couldn’t crack. We were barely holding this thing together. It was very important to always give my team the impression that this was absolutely possible.”

In addition to their disagreement on puppet design, Rogoff and her Russian colleagues had differing opinions on nearly every aspect of the show, including its music, set design, and the educational goals of the program. The issue of puppet design continued until some of the artists visited New York City, where they saw the Sesame Street set and met the puppeteers. After that, says Rogoff, “they embraced Muppets wholeheartedly.”

Ulitsa Sezam’s puppet characters were recognizably Muppets but distinctly Russian. An oversize “walk-around” puppet named Zeliboba was a nine-foot-tall furry blue dvorovoi: a spirit of Russian folklore representing home, hearth, forest, and courtyard. He would become a familiar character to Russian viewers, the equivalent of the American Big Bird.

But not every difference between American and Russian philosophies could be reconciled in Ulitsa Sezam, says Rogoff. She remembers one writer’s storyboard in particular, in which a little girl and boy held hands while walking in a park, each of them clutching a balloon. The little boy accidentally releases his balloon and starts to cry. The girl smiles at him: It’s OK! She lets go of her balloon, too.

“They stand together, hand in hand, and watch the balloons go up into the cloudless blue sky,” says Rogoff. The goal of the segment was to teach children the difference between happy and sad.

“When I saw the script, I just laughed,” says Rogoff. She asked the writers why the children didn’t just share the other balloon. Then it was the writers’ turn to laugh at Rogoff. “They said, ‘Natasha, that is such an American perspective.’ ” The children were happy, the writers explained, because they were sharing something else — not a balloon but a lack of something. They had nothing, together.

“That is what I love about Russia,” says Rogoff. “It can be a very spiritual place alongside the darkness, brutality, and violence.”

Ulitsa Sezam went off the air in 2010 when Russian President Vladimir Putin seized more control over independent television. “When I look back on it,” says Rogoff, who now lives in Cambridge and New York City, “I can’t believe we were actually able to do it.”

The memories of Ulitsa Sezam live on. At her book events over the past two years, Rogoff says, she’s met Russians, Georgians, Armenians, and Ukrainians. “In London, especially,” she says, “there were a lot of Ukrainians, mostly women who had left with their children when the war started. They grew up on the show the same way Americans grew up on Sesame Street. They felt it had changed their lives.”

Puppet Parley

The event: Natasha Lance Rogoff, author of Muppets in Moscow, in conversation with Ed Christie

The time: Saturday, Sept. 14, 6 p.m.

The place: East End Books, 389 Commercial St., Provincetown

The cost: $5 to $25 at eastendbooksptown.com