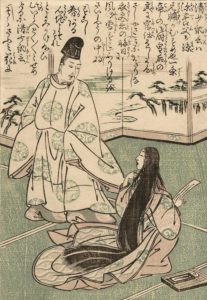

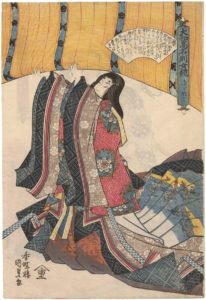

A thousand years ago, Sei Shōnagon set down on paper her wry observations of court life in Kyoto, the capital of Heian Japan. What was awkward to Sei? “The back side of a sumo wrestler who has just lost his match.” What sorts of things did she consider better big than small? Houses, lunchboxes, monks, cows, pine trees, brooms, and blocks of ink.

For a millennium, Sei’s words have been passed down as The Pillow Book, a celebrated work of classical Japanese literature. The book’s name references both the fluffy white paper on which Sei wrote (which she thought looked like a pillow) and how she accidentally left the stack of paper, a journal of sorts meant only for herself, at the head of a guest’s bed, leading to its circulation.

Readers of English have encountered Sei’s writing through translations by Theobald Andrew Purcell and W.G. Aston (1889), Arthur Waley (1928), Ivan I. Morris (1967), and Meredith McKinney (2006). Viewers may have seen a sexed-up version of Sei’s classic in director Peter Greenaway’s 1996 film, which was only loosely based on Sei’s book.

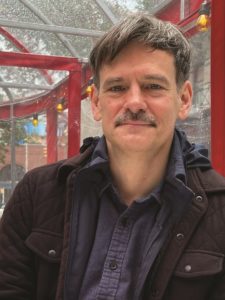

Now, listeners have an opportunity to encounter The Pillow Book courtesy of J. Keith Vincent of Wellfleet. Vincent helped produce an hour-long version of Sei’s work for the Alexander app. An associate professor at Boston University, Vincent teaches comparative literature, gender, and sexuality studies. He specializes in translation.

Vincent was already taken with Sei’s observations of the minutiae around her. He had long savored The Pillow Book and taught it to undergraduates. Given his interest in gender, Vincent was curious about Sei’s status both as a writer and lady-in-waiting. She grew up in a celebrated literary family and learned classical Chinese and Japanese. She was also groomed to become a court attendant to Empress Teishi, a consort of the emperor.

But until he was approached to work on the abridged audio version of The Pillow Book, Vincent had never tried his own hand at translating it. Film producer Cameron Lamb created Alexander, an app for mobile devices, with the goal of adapting an array of nonfiction works into hour-long productions. Lamb didn’t want footnotes or an introduction, which he imagined would prevent listeners from diving headlong into the abridgement of The Pillow Book.

As a scholar, Vincent initially found Lamb’s parameters off-putting. He was worried that, without academic conventions to provide context, modern listeners wouldn’t understand what they were hearing. He fretted that Lamb and his team might be “Silicon Valley types” unfamiliar with the nuances of translation and the problems of abridgement. “Would they even understand what it means to commission a work such as this?” he wondered.

Vincent read and translated The Pillow Book each morning last summer at his home in Wellfleet. As he sifted through the more than 400 pages of text, Vincent used a spreadsheet to sort what he read into topics and themes. He enjoyed his efforts but was stymied as to what to emphasize and what to leave out.

A strategy presented itself when he awoke startled one night. Rather than following the structures previous editors and translators had set out, Vincent decided to showcase Sei’s descriptions of herself as a court attendant. The focus would allow Sei to explain herself as an exceptionally literate, readerly lady-in-waiting. Vincent hoped listeners would come to know Sei as she understood herself.

Vincent omitted some sections and rearranged others. He acknowledges that other translators might find his choices shocking. “You could say that I tore things out of context,” he says. But, he adds, scholars don’t actually know how Sei organized her writing, so perhaps his liberties aren’t so radical after all.

Vincent has more than accomplished the goals both he and Lamb envisioned. Whether or not they are familiar with The Pillow Book, listeners will find Vincent’s translation irresistible. Narrator Haruka Kuroda, a voiceover artist, brings Sei to life, making her words sing with verve and wit. Listen to Kuroda crisply pronounce the words “duck eggs,” and you will instantly appreciate why Sei thought them “elegant.”

Vincent has done a wonderful job selecting and organizing some of Sei’s famous lists. I laughed in recognition at Sei’s list of things that should be short, two of which are “a serving woman’s hair” and “speeches made by other people’s daughters.”

“Irritating things” make up the longest list Vincent includes. Kuroda delivers these with petulance:

“A guest arrives just when you are in a hurry to get somewhere and drones on and on.”

“A man who has nothing in particular to recommend him keeps grinning and grinning at you and won’t stop talking.”

Drunken men, fleas, barking dogs, flies with their “little wet feet” — these irritations are as bothersome now as they were a thousand years ago.

Once he had finished translating and abridging the anecdotes, observations, and lists, Vincent says, there was a conflict over who would give voice to Sei’s words. Editors at Alexander wanted to use a performer born in Japan whose first language was Japanese, but Vincent found her English difficult to understand. He didn’t believe the performer needed to be a native-born Japanese speaker.

“The whole point of translation is to make it seem as if it were written in the target language,” he says. “You wouldn’t expect Proust to be read with a French accent.”

In the end, Vincent says, the editorial team selected Kuroda, not the initial choice, to give voice to Sei’s words. Kuroda, whose first language is Japanese, lives as an English speaker in London. After he listened to the final mix, Vincent was delighted. “I couldn’t imagine it being better,” he says.

As for Sei, Vincent thinks she, too, would have been delighted by the production. In one of Sei’s poems, she counts as a particular delight the possibility that someone might start quoting a poem of hers. “This has yet to happen to any of my poems,” she writes, “but I can easily imagine how happy it would make me if it did.”

Listeners can find Vincent’s adaptation of The Pillow Book on the Alexander app, available in iOS and Android platforms. The app allows listeners to select one work as a free trial.