PROVINCETOWN — The lack of affordable and available year-round housing is a crisis on the Outer Cape, but at least it’s one for which communities have tools — from federal and state programs to local solutions such as Provincetown’s Year-Round Market-Rate Rental Housing Trust to a variety of accessory dwelling unit bylaws.

A significant part of the Outer Cape’s workforce is seasonal, however. While some who work in hotels and restaurants live here full-time, many arrive here in spring and stay only through the fall.

“Workforce housing” is being discussed in public forums, but when it comes to actual policy, it’s mostly left to the private sector to figure out. There isn’t federal or state money to help support seasonal housing. And seasonal workers usually don’t vote here.

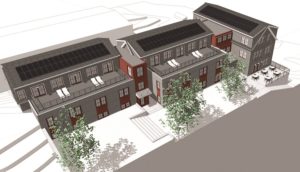

Patrick Patrick, the owner of Marine Specialties and the chair of the Provincetown Chamber of Commerce, has proposed building a seasonal dormitory called “the Barracks” that could house up to 144 people on land his family owns off Route 6. The project would be privately owned and funded. His proposal has already been approved by the select board and the zoning board of appeals, and will be on the planning board’s agenda soon.

Meanwhile, the select board has a new economic stabilization and sustainability advisory committee, on which Patrick serves. He and others are discussing housing ideas there, including that — for a business community at its wits’ end — the solution might be: go big.

Patrick began working on the Barracks idea eight years ago. But, he said, he got serious in 2019, when “the housing for my own staff became so impossible that almost all our returning people moved into my parents’ house.”

From Patrick’s point of view, the market is about to shift even further, as Covid-inspired demand and other demographics converge. “I estimate there are about four to six families who own a large percentage of the remaining rental inventory — probably about half,” he said. “Some of them are well into their 70s. Some of them are older than that.”

The problem, he said, is that if these properties change hands in today’s market, they are very likely to become vacation homes. While many of them would then be offered for rent, it would be on the short-term vacation market, not the season-long workforce one.

“I predicted three to five years ago that we would hit a wall in a really dramatic fashion right about now,” said Patrick.

The scale of the problem is hard to measure. There are about 290 residential units with a seasonal rental certificate in Provincetown, out of about 4,700 total units. With only 6 percent of the town’s units registered as seasonal rentals, there could easily be more that are unregistered.

Meanwhile, Provincetown goes from about 1,500 active employees in March to about 4,200 in July, according to the Cape Cod Commission (datacapecod.com). While some of those 2,700 seasonal jobs go to permanent residents, if even half go to seasonal people, that means housing 1,350 people.

Another way to estimate the need is to look at the seasonal workers whose numbers are known: J-1 and H-2B visa workers. In the years before the pandemic, about 500 J-1 college student workers, mostly from Bulgaria and other Eastern European countries, were sponsored by Provincetown businesses. There were also about 500 H-2B visa workers approved for Provincetown businesses, the majority of them from Jamaica.

Add in the Americans who arrive from Boston, New York, and other places, and the number could easily swell to 2,000 seasonal workers.

As housing units disappear into the vacation rental market, those workers are crowding into fewer and fewer apartments.

The state’s Code of Human Habitation has rules for safe occupancy, particularly because of fire danger. “Without a project like the Barracks, I don’t know how we get that number of seasonal housing units in this town,” said member Louise Venden at the select board’s April 12 meeting. “Unless we are going to continue jamming 6 or 7 people into one-bedroom apartments — which we have done.”

Some larger employers have resorted to buying residential units just to house staff. This is expensive for those who attempt it, and impossible for most smaller businesses.

There were 1,148 “entire homes” listed as short-term rentals on Airbnb, VRBO, and Homeaway in August 2019, the most recent pre-pandemic peak, according to market research website AirDNA. Since then, more than 500 properties have changed hands in Provincetown, according to the town assessor’s ownership list.

The law that established the short-term rental tax in Massachusetts, signed by Gov. Baker in December 2018, gives towns the right to regulate the number of local licenses or permits issued and the number of days a property owner may rent out accommodation. The law also allows a community impact fee, equal to 3 percent of sales, on “investor-owned properties,” which are defined as two or more properties that are on a different lot from the owner’s primary residence.

No towns on Cape Cod have made use of any of these provisions, however. Only about 20 towns in the state have applied the community impact fee.

The way Patrick sees it, if the attrition in housing can’t be slowed, production needs to accelerate. “If people can still find properties to build condos, then you can find properties to build workforce housing,” he said. “There are a number of parcels that are underutilized.” A big building might be out of place in some areas, he said, but a cluster of tiny homes might fit in well.

“Once I’ve got this current project up and running,” he said, “I think I’d be looking to see if I can do more.”

The economic stabilization and sustainability advisory committee meetings are public and held online every other Wednesday at 4:30 p.m. For information go to provincetown-ma.gov, click on Town Boards, then look under Temporary Boards.