It’s Jupiter and Saturn season, the time of year when both planets are favorably positioned in the sky after sunset. Over the next few weeks, you can find and appreciate them easily with the unaided eye as pretty and colorful stars. And if you have binoculars, you may be astonished at the detail you can see with them.

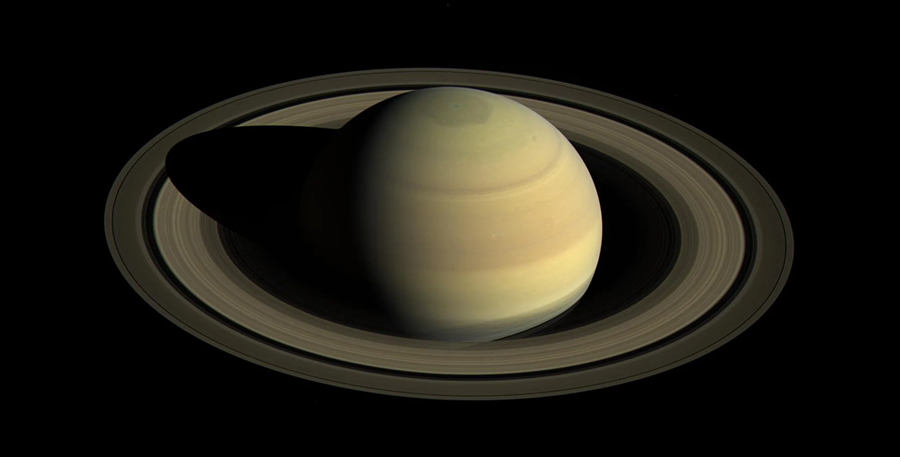

Saturn is probably the planet most casual skywatchers know best, after our own: its rings, whether seen in NASA photos or through a telescope, are an unforgettable sight.

The planet’s name comes to us from the religion and mythology of the Romans. Saturn was a Roman god associated with agriculture, renewal, wealth, and freedom. Roman mythology refers to an ancient Golden Age when Saturn ruled over all creation, and humanity enjoyed peace and prosperity — without having to do any work.

Much later, having learned the value of hard work, the Romans conquered Greece. The conquerors of the first century B.C.E. admired and envied Greek culture and ideas. Among many acts of cultural appropriation, which included stealing art, they adopted Greek deities and, in one of the great retcons of history, identified them with their own Roman deities. Zeus, Hera, and Aphrodite, with a few modifications, became Jupiter, Juno, and Venus. And Kronos, leader of the Titans who ruled before the more familiar Greek gods, became Saturn.

There are five stars that follow strange, meandering paths in the sky. Their motion is markedly different from the two thousand or so other well-behaved stars. The ancient Greeks called them planetes — wandering stars. We know them today as the five planets in our solar system that are visible to the unaided eye.

The Greeks called one of these wandering stars Kronos in honor of the Titan. The Romans called it Saturn, and that name has stuck for the cultural descendants of ancient Rome.

Saturn is about 800 million miles from Earth and is a huge planet, second only to Jupiter in size. Our planet is about 7,900 miles in diameter; Saturn is about 75,000 miles across. You could pack 764 Earths inside it. Astronomers categorize Earth as a terrestrial planet, meaning it’s mostly composed of iron, nickel, and rock, with a relatively thin atmosphere. In our case, it’s about 62 miles thick and, at lower altitudes, very pleasant. Saturn is a gas giant, made almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, with an immensely thick atmosphere. And it’s not a pleasant one at any altitude.

If you could descend into Saturn’s atmosphere in a spaceship, you’d first pass through a layer with ferocious winds blowing over 1,000 miles per hour and clouds made of ammonia ice. Temperature and pressure would increase rapidly as you descended, crushing or baking your spaceship long before you could reach a deep sea of liquid hydrogen. Below that sea the hydrogen, under ever-increasing heat and pressure, transitions to a bizarre metallic hydrogen, which has properties of both liquid and solid. Finally, there is a dense rocky core, similar to Earth’s in composition, but much larger and under extreme heat and pressure.

Saturn’s magnificent rings are made of countless small pieces of ice, which range from the size of pebbles up to about 30 feet. The rings are about 170,000 miles in diameter (with an enormous gap in the center for Saturn). But this vast structure is, on average, only 60 feet thick. Ice reflects sunlight very well, which is why the rings are visible.

Our best evidence to date suggests that the rings are the remains of an icy moon whose orbit decayed, causing it to lose altitude and venture closer and closer to Saturn and its powerful gravity. Once it got too close, tidal forces (like those between Earth and our moon that cause ocean tides) tore the moon apart. The debris then spread out into the rings we see today. This probably happened about 400 million years ago. (The Sun and planets, including Earth, formed about 4.5 billion years ago.)

About 300 million years from now the rings will be gone, as piece by tiny piece the ice succumbs to Saturn’s gravity and falls into its atmosphere. It’s happening even now as you read this.

To find Saturn in the sky, head outside on any clear evening before the end of the year. Give your eyes time to adjust to the darkness, then look to the southwest. Saturn is not a bright star, but its color is a distinct yellow-gold. Some people see it more as red-gold — individual color perception in dim conditions can vary. And in contrast to true stars, planets don’t twinkle (usually). If you see a star in the southwest that’s any kind of gold hue and doesn’t twinkle, you’ve found Saturn.

If you have binoculars, rest them on a railing or tree branch and point them toward Saturn. With a steady view Saturn will appear as an oblong shape like a football. Children and adults with very sharp eyesight may be able to resolve the rings. And anyone will be able to see at least one pinprick star very close to Saturn. That’s Titan, its largest and brightest moon. (Saturn has over 100 moons, though most of them are just large rocks and chunks of ice.)

Saturn’s Golden Age is over. But Roman mythology doesn’t say that it was necessarily the one and only time that Saturn might rule over humanity. I’m looking forward to peace and prosperity without the hard work in some future Golden Age Part Two. Clear skies!