Outside her home in the woods of South Wellfleet, Sara Moran is making a shrine.

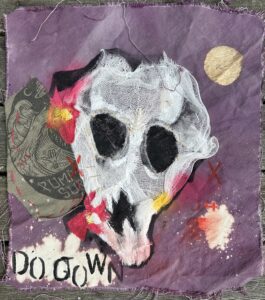

The broken seat of a wooden chair leans against a piece of wood, which is rounded at the top like a rustic makeshift surfboard. A pair of plastic goggles hangs from a notch in the wood. In the center, propped at an angle atop the bottom jaw of a sea creature, is a painting of a seal’s skull with deep shadowed eye sockets and a jagged nasal cavity. In the top right corner of the painting is the suggestion of a full Moon. Two rocks, partially painted bright red, claim spots on either side of the skeletal jaw. The whole thing feels resourcefully, defiantly religious.

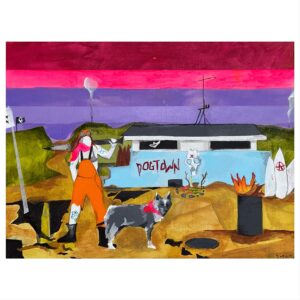

“It’s an altar for survivors,” says Moran about the assemblage. The work-in-progress is part of Moran’s current show, “Until the End,” at Alias Gallery in Orleans, a novelesque collection of wood-panel paintings, fabrics, and sculptural totems that are meant to tell the story of a post-apocalyptic Wellfleet and its inhabitants.

Moran’s 14-year-old dog, Lupé, leads the way inside the house. On the stairs, other pieces from the series are on display: ragged-edged squares of canvas, dyed purple and haphazardly bleached and decorated with torn-up bits of old T-shirts, strips of gauze, and pieces of string. Some feature the image of the seal skull. One shows the shape of part of a monkfish jaw. The word “Dogtown” appears on one, etched in black like bold graffiti.

“They’re flags,” says Moran about the canvas pieces, explaining that “Dogtown” is a reference to the history of South Wellfleet. As she understands it, it’s a slang term for a part of town where dogs roam, often around a train station.

“Right where Blue Willow is there was a train station,” she says. In Moran’s vision of a post-apocalyptic Wellfleet, the people who are left form a community and call it Dogtown.

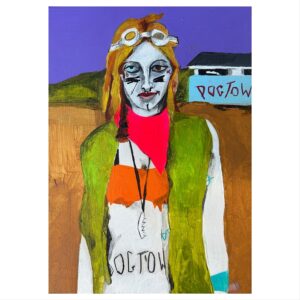

The Dogtown crew is a group of women who appear in portraits sporting matching hot-pink neck scarves, tattoos, and campfire soot under their eyes. Their home base is Lecount Hollow Beach. The name of their community is written on a blue wall visible behind them. Its “mascot” is a coyote named “Elma,” says Moran. (Elma also wears the signature pink scarf.)

All the Dogtown women wear the same necklace, another mark of their belonging. It’s half of a small white monkfish jaw, dangling from a black string — the same bone that appears on one of their flags. Moran, who has lived in Wellfleet for 10 years, found the piece of bone at Lecount Hollow, where she surfs regularly.

“In some ways, it was the start of the show,” she says. “I was really fascinated by it.” She thought it could make a good necklace or earring. As she holds it up to her face, the tiny white teeth brush against her cheek. Despite the softening touch of sea and sand, they still look painfully sharp. “But my imagination started to go further with it.”

“I grew up watching Mad Max,” says Moran. “It was my dad’s favorite movie.” Along with other movies from the 1980s and ’90s lurking in the back of her mind — Moran mentions The Lost Boys and The Warriors — it rose to the surface during the pandemic when her imagination began to change the landscape around her into one where people catch fantastical, disfigured fish, wear torn clothing, and surf the waves at Newcomb Hollow.

“That sealed my relationship with Wellfleet,” she says. The show’s title references the idea of where one might spend the end of one’s days. For Moran, that place is the Outer Cape. “In some ways,” she says, “the show is an ode to Wellfleet.”

Moran says she is a “process artist.” Her pieces, like the canvas flags, tend to come together in what she calls a “flow state” — “It’s only after I’m finished that I understand what I’ve made,” she says. Aside from making art, she teaches in the Expressive Therapies department at Lesley University in Cambridge and works as an art therapist in private practice. All of her work is about exploration. “It’s about utilizing the creative language and asking novel and interesting questions,” she says.

Another part of “Until the End” involves what Moran calls “totems”: small rectangular prisms, painted white and decorated with oil paint, gold tape, string, and stenciled letters, images, and words. The totems are examples of the products of Moran’s exploratory, unconscious process. For the Dogtown crew, they’re sacred things to hold on to. In the show, “they might be surrounding the altar,” she says.

The whole show is strangely direct, as if it’s violating some agreed-upon distance between viewer and subject. The women in the portraits make direct eye contact with the viewer. When Moran was painting DT2 — the women have abandoned their names in favor of more anonymous abbreviations — she added a line on the corner of her smirk. “All of a sudden, I got a sense of her character,” she says. “They start to talk to you. Like, ‘Oh, that’s who you are!’ ” DT2, she says, is mischievous. She’s up to something. For the show, Moran will include descriptive narratives to go along with the paintings.

Although the subjects of her paintings wear gas masks while they surf the toxic ocean, look to dogs for spiritual guidance, and paint seal skulls on their banners, which fly under a sickly purple sky, Moran says that “Until the End” isn’t meant to be scary, or at least not entirely scary. “I was thinking of it as playful,” she says.

That sense of play is visible in Beach Fort, which depicts two people resting under a makeshift fort on the beach with a swing set in the background. In the foreground, a sign warns visitors to “GO AWAY.” It’s as though the inhabitants of Dogtown are saying: Please don’t disturb us. We’re fine where we are.

‘Until the End’

The event: An exhibition of multimedia art by Sara Moran

The time: On view through Tuesday, Aug. 20

The place: Alias Gallery, 64 Main St., Orleans

The cost: Free; see aliasgallery.com