Honestly, the word “Afro-Cuban” was not top of mind when I walked into the Sandwich Glass Museum. But as I looked in wonder at David McDermott’s huge glass sculpture hanging above me, I heard a distant drumming. Odd, I thought. Taking a left into the museum, I saw Hoyt Hottel, his back arched like a yogini, his instrument pointed skyward, cheeks puffed out like Dizzy Gillespie, blowing what looked like it could have been a very high note.

At the tip of Hottel’s instrument was a glowing orange orb. It was expanding like a balloon. Molten glass, not music. He was midway through his glassblowing demo, which is repeated throughout the day, so I ventured off, planning to catch the show later from beginning to end.

I followed the drums. Glass artist Robert Dane and painter Carl Lopes both love Afro-Caribbean music and have combined their sculpture and mixed-media works in “Heartbeats and Harmony,” an exhibition that runs through Nov. 2. Lopes, who has Cape Verdean roots, is from New Bedford, which has its own notable glassmaking history. Dane, who is both a musician and an artist, started blowing glass in the 1970s when he was a student at Mass College of Art and has since trained with Lino Tagliapietra and other masters. It’s hard to comprehend how the masks, busts, and shields the two collaborated on are made of glass.

Even beyond this current exhibition, the museum is a riot of color, light, and form. Taking advantage of the building’s numerous windows, the curators display the glass on shelves so that natural light shines through and splashes about.

There’s an intentional route laid out by the curators, one that traces the history of glassmaking and of the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company in particular. I took a scattershot approach, however, only because I was continually drawn here and there by a shaft of ruby-colored light or some cobalt blue, then a widow display of a hundred or more sparkles backdropped by blue sky and white clouds.

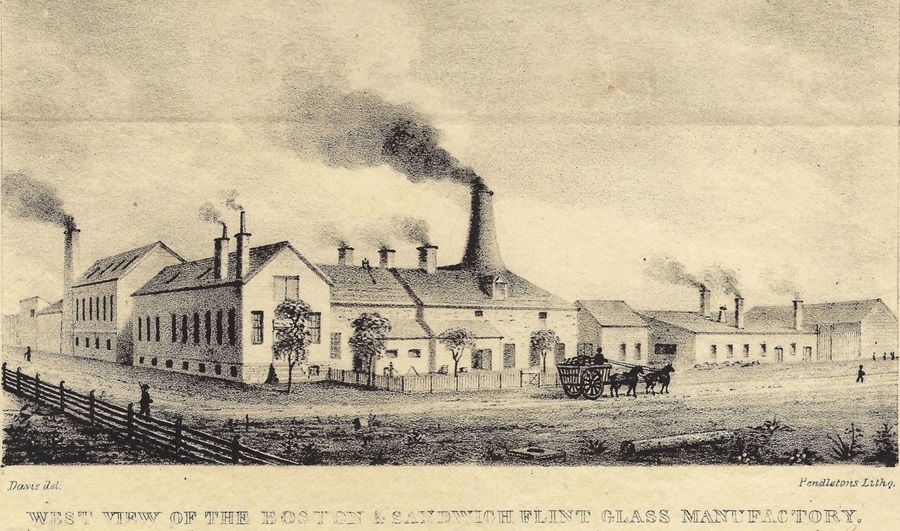

Taking a seat for the every-half-hour video, I learned that Sandwich was not chosen by Deming Jarves for the location of his Sandwich Glass Manufactory in 1825 because of its sand. (It’s too coarse and dirty; a much finer grade of sand than that of our beaches is required for glassmaking.) Instead, Jarves, who in 1818 had been a founder of the New England Glass Company in Cambridge, built here because of something that today is hard to imagine: the area’s copious supply of wood to fire the furnaces. Here, too, was salt hay to pack the glass in. And a harbor.

The year after the factory was built, Jarves folded it into his Boston and Sandwich Glass Company. It thrived as the population of Cape Cod and the entire country grew and so did demand for glassware.

Jarves was quick to adopt pressing machinery and even patented some improvements in molding techniques. By 1827, the Sandwich factory began to blow hot glass into full-sized patterned molds. You’ve perhaps seen some of the antique pieces, a vase or pitcher, tastefully placed on a shelf catching the sun in its pebbled and etched blue surface. This mechanization did not require the skill of a Hoyt Hottel, and soon the factory was stamping out plates by this process at the rate of 264 per worker per shift.

For a time, the factory in Sandwich was the biggest glass producer in the country, with 500 employees. The mammoth plant made glass in all forms, blown and pressed, for 62 years. 1887 brought a nationwide glassblowers strike — a blow from which the factory never recovered. Meanwhile, glass production shifted from New England to coal country and the Midwest.

On the way to see Hottel’s demonstration, I stopped before a display that I had missed. It read: “Glass is made of silica. However, it does not melt until it reaches a temperature of 3,078 degrees F.”

“Hoyt!” I thought. But there was Hottel, calmly making pumpkins out of the molten glass. Pearls of sweat glistened on his upper lip as he kept up an educational banter. He opened the small doors to the glowing furnace. A soft orange blob hung from the end of his blowpipe.

“You can pinch it, blow it up, twirl it, squeeze it,” he said as he raised the molten material high in the air, brought the mouthpiece to his lips, and, like a New Orleans trumpeter, blew. The hot orb expanded. He then lowered it carefully, sat, and began to twirl the pipe as it lay horizontally supported across his legs. With his heavily gloved hand and some wet fabric he smoothed the glowing mass into a more regular spherical shape. While it was still attached to the pipe, he placed it in a mold to give it some pumpkin ridges. He was moving quickly and smoothly.

“This is a jacks,” said Hottel, holding a rather large tweezer-like implement. “A glass blower can do a lot with this simple tool.” He dipped the pumpkin in some metallic oxides for color and returned it to the furnace for a quick heat-up. Out it came, glowing — the color would emerge only as it cooled.

There are still a number of glassblowers in Sandwich, Hottel said. “David McDermott, down the road, has a Scottish glassblowing lineage going back 500 years. He’s the real deal — still has his family tools.”

Magically (for one can only see this as magic) Hoyt pinched off the top of the molten pumpkin with his jacks and placed it on a graphite pad on a nearby table. He heated up a rod and — don’t ask me how even though I was right there — fashioned a curled stem out of a glowing gooey remnant.

“We have to get this into the oven now because it can’t cool too quickly,” he said. “We’re against the clock, because if the temperature of the glass drops too fast it will either crack or explode into a thousand pieces into every part of this room.”

With that, like a baker with a freshly formed pie, Hoyt shuffled over to the side of the large brick furnace, opened the oven door, and gently slid the pumpkin onto a rack.

“It’ll be done in the morning.”

After Hottel pulled off his gloves and took questions, I made one last pass through the bright rooms, seeing a bold molten orange glow behind every sparkling pitcher and plate and prism.

I overheard him say to a lingerer, “Yeah, I can’t believe they let me play with fire.”

I have one of Hottel’s pumpkins now. It’s weighty and cool to the touch and etched with his mark in the bottom, HCH.