WELLFLEET — Throughout August, the Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater spritzed the outdoor set of Nat Turner in Jerusalem with bug spray, so performers Ricardy Fabre and Robert St. Laurence could deliver their lines without flinching. At one point, a mosquito landed on Fabre’s forehead. He stayed in character, unfazed. Audience members, however, scratched, swatted, and swore their way through the show, even after someone passed around a bottle of Off!

Documenting this year’s mosquito invasion, an undertaking I inherited from our summer fellow Ben Glickman, was my way into the salt marsh beat. I tromped into the belly of the Herring River basin — the epicenter of the mosquito boom — following people from the Cape Cod Mosquito Control Project. There, I got mauled by what Ben had called “bloodsuckers.” My legs are still mottled four months later, thanks to Ochlerotatus sollicitans, the Eastern salt marsh mosquito.

A winter storm had laid the groundwork for this year’s plague, flattening the coastal bank at Duck Harbor. Waves from Cape Cod Bay then washed over it, spilling into the Herring River basin, where the water stayed put, offering mosquitos an expanse of prime real estate for breeding.

Gabrielle Sakolsky, Cape Cod Mosquito Control’s superintendent, and her crews scrambled to treat those Herring River waterways with larvicide — at best, a short-term fix. A more substantive strategy will come from restoring the tidal flow, but the river’s restoration is still years away.

In the meantime, Sakolsky’s team set out to reopen long-abandoned mosquito ditches — channels splintering off the Herring River that were used in the past to keep water flowing, which helped ward off mosquitos because they prefer standing water for egg-laying.

2022 Is Looking Better

After extensive discussions, Cape Cod National Seashore officials have allowed Mosquito Control to pull fallen trees from the ditches, and Sakolsky has been seeing two promising signs. “The water is moving through the system at a very fast rate at this point,” she told me. “You’ll see leaves and pine needles being pushed through with a lot of force.”

And she’s spotted fish. They help control the population of larvae, which they find tasty.

Sakolsky, meanwhile, is discussing a larvicide permit with the Seashore for the coming spring — issued ideally by April 1 to best pre-empt another summer of infernal torment. “It’s looking very promising for next summer,” she said. “It will be a better 2022.”

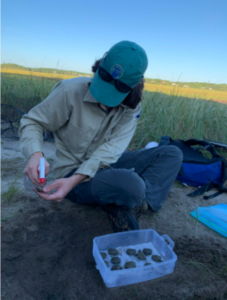

Fortunately, not all salt marsh denizens are as aggressive as O. sollicitans. The diamondback terrapin, a threatened turtle species, is shyer. These guys also had a monumental year: on Sept. 3, the day after Hurricane Ida’s remnants blew through, Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary responded to what one volunteer called a “gold rush” of terrapin hatchlings. They were found emerging by the dozen on Lieutenant Island, where they were met by volunteers trained to dig the turtles out of the sand and ready them for safe release.

This year, the sanctuary’s team released 5,162 baby turtles from 419 protected nests — an all-time high for the program.

The salt marsh itself, forged by stretches of Spartina alterniflora, the smooth cordgrass, also needs a leg up, especially as climate change brews and human development encroaches.

At a Sept. 23 National Seashore symposium, Katie Sperry, a researcher from Northeastern University, reminded us why this marsh grass matters: Spartina cushions us from storm surges and offers erosion protection.

Spartina, when paired with a sea breeze, can, however, thwart those hoping to hit a birdie, as I learned reporting on one of Eastham’s secrets, the quirky and now-disappeared Cedar Bank Links (buried under the Seashore’s Salt Pond Visitor Center, the town hall, and the Nauset Inlet). The links had a penchant for gobbling up golf balls. They trumped even Francis Ouimet and Bobby Jones, both U.S. Open champs. Jones, to his credit, did come close. In 1931, he shot Cedar Links’ best score ever: a 73, one over par.

The links did not last, but Spartina’s hardiness amazes. Its blades are drenched in salt water, and roughly six hours later, the marsh drains out, leaving the landscape mucky and muddy. Another six hours later, Spartina — adapted to this seesaw of an ecosystem — is inundated once more, and so it goes.

Folks living on Lieutenant Island in Wellfleet likewise must adapt to the tides. A one-lane wooden bridge connects the island to the rest of the Cape. Twice daily, that high tide floods the road leading up to that crossing, so a poorly timed return from dinner could mean, for some seasoned islanders, parking the car, peeling off socks, and sloshing through the causeway. Others just sleep in the back seat.

But unwitting visitors who plow through the salt water may find their vehicles sputtering into the marsh, the engine stalled (and soon, rusty). These logistics got even trickier when, in November, the bridge underwent repairs that permitted residents only a wafer-thin 30-minute window for crossings during the workday.